High-performance ceramics often appear complex and inaccessible; however, zirconia ceramic bridges natural mineral origins with engineered reliability. Consequently, understanding its material foundation clarifies why this compound underpins demanding industrial environments.

Zirconia ceramic refers to zirconium dioxide-based ceramics whose properties evolve from natural mineral forms into engineered solids. Overall, its scientific relevance emerges from crystal chemistry, thermodynamic behavior, and structural adaptability across extreme conditions.

Before examining engineered performance, it is essential to trace zirconia ceramic back to its natural occurrence. Accordingly, the following section establishes the geological and chemical origins that define its intrinsic material boundaries.

Discussions surrounding zirconia ceramic frequently begin with fundamental questions about its existence in nature, its chemical identity, and its inherent stability. Therefore, clarifying these origins provides a necessary baseline for later engineering interpretations.

Zirconia Ceramic as a Naturally Occurring Material

Zirconia ceramic originates from naturally occurring zirconium-bearing minerals rather than synthetic invention. Consequently, its industrial relevance is grounded in geological abundance, chemical stability, and crystallographic identity formed long before technological processing.

Zirconium minerals and geological occurrence

Zirconium primarily occurs in the mineral zircon, chemically expressed as ZrSiO₄, which forms within igneous and metamorphic rocks. Notably, zircon crystals are widespread in continental crust, with average concentrations ranging from 150 to 300 ppm in granitic formations.

Furthermore, zircon demonstrates exceptional resistance to weathering, allowing grains to persist in sedimentary deposits for billions of years. As a result, heavy mineral sands often contain zircon contents exceeding 1–5 wt%, making them practical sources for zirconium extraction.

Ultimately, these geological characteristics explain why zirconium supply remains stable and globally distributed, providing the raw basis for zirconia ceramic without reliance on rare or geopolitically constrained resources.

Chemical composition and crystallographic identity

Pure zirconia ceramic consists of zirconium dioxide, ZrO₂, a binary oxide with strong ionic bonding between Zr⁴⁺ and O²⁻ ions. At ambient conditions, ZrO₂ adopts a monoclinic crystal structure characterized by asymmetric lattice parameters and limited atomic mobility.

However, crystallographic studies show that zirconia undergoes phase transformations at elevated temperatures, transitioning to tetragonal form above 1170 °C and cubic symmetry beyond 2370 °C. These transformations are accompanied by measurable lattice rearrangements rather than compositional change.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic is best described as a polymorphic material whose structure is temperature-dependent, a property that later becomes central to its engineered performance.

Thermodynamic stability in natural environments

In natural geological settings, zirconia exhibits high chemical inertness and thermodynamic stability. Specifically, ZrO₂ possesses a standard Gibbs free energy of formation1 near −1040 kJ/mol, indicating strong resistance to spontaneous decomposition.

Moreover, zirconia remains insoluble in water and shows negligible reactivity with most acids and alkalis below 200 °C. This stability explains the persistence of zircon grains across repeated geological cycles of erosion and deposition.

As a consequence, the inherent durability observed in nature establishes zirconia ceramic as a material predisposed to long-term stability when later subjected to engineered service conditions.

Natural origin characteristics of zirconia-based materials

| Property (Unit) | Typical Value |

|---|---|

| Average crustal abundance (ppm) | 150–300 |

| Dominant host mineral | Zircon (ZrSiO₄) |

| Gibbs free energy of ZrO₂ formation (kJ/mol) | ≈ −1040 |

| Monoclinic phase stability limit (°C) | < 1170 |

| Water solubility at 25 °C | Negligible |

These naturally stable zirconium minerals establish the chemical and crystallographic foundation upon which later zirconia ceramic engineering becomes possible.

Zirconia Ceramic in the History of Materials Science

Subsequently, once the natural identity of zirconia ceramic is established, attention shifts toward its intellectual and technological recognition. Therefore, tracing its historical path explains how an abundant oxide evolved into a strategically important engineering material.

Zirconia ceramic did not enter materials science as a finished solution but as a problematic compound whose brittleness limited early use. However, progressive advances in crystallography, thermodynamics, and microstructural control gradually repositioned zirconia from a laboratory curiosity to a cornerstone of structural ceramics.

Historically, this transition reflects broader shifts in materials science, where understanding internal structure became as critical as chemical composition. Accordingly, the following subsections outline how zirconia ceramic earned its place through successive scientific milestones.

Early scientific recognition of zirconia

Zirconium compounds were first isolated in the late eighteenth century during systematic studies of refractory oxides. Specifically, zirconia was identified as a high-melting oxide with a melting point exceeding 2700 °C, immediately distinguishing it from alumina and silica.

Moreover, nineteenth-century chemists observed that zirconia retained structural integrity at temperatures where common oxides softened or volatilized. As a result, early furnace experiments noted its resistance to deformation during prolonged heating cycles.

Nevertheless, despite its refractory nature, zirconia ceramic remained largely confined to academic study due to processing difficulty and unpredictable cracking during cooling.

Challenges of brittleness in early zirconia ceramics

Early sintered zirconia ceramic components exhibited catastrophic fracture with minimal warning. Quantitatively, fracture toughness2 values remained below 2 MPa·m¹ᐟ², placing zirconia alongside other brittle oxides unsuitable for load-bearing roles.

In addition, uncontrolled phase transformation during cooling caused volumetric expansion approaching 3–5%, inducing internal stresses that exceeded tensile strength limits. Consequently, large components frequently failed during cooling rather than service.

These limitations created a perception that zirconia ceramic was inherently unreliable, delaying industrial adoption despite its attractive thermal properties.

Breakthroughs leading to structural applications

A decisive shift occurred in the mid-twentieth century with the discovery of phase stabilization through aliovalent oxide additions. Notably, small additions of yttria in the range of 2–8 mol% altered phase equilibria, suppressing destructive monoclinic transformation.

Furthermore, researchers identified transformation toughening, where controlled tetragonal-to-monoclinic conversion near crack tips absorbed fracture energy. Measured fracture toughness values consequently increased to 6–10 MPa·m¹ᐟ², rivaling some metallic systems.

Ultimately, these breakthroughs redefined zirconia ceramic as a mechanically viable material, enabling its transition from refractory oxide to engineered structural ceramic.

Historical milestones in zirconia ceramic development

| Period | Key Advancement | Quantitative Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Late 1700s | Chemical isolation of zirconia | Melting point > 2700 °C |

| Early 1900s | Refractory evaluation | Stable above 2000 °C |

| 1950s–1960s | Phase stabilization concepts | Volume change reduced < 1% |

| 1970s | Transformation toughening theory | Toughness increased to 6–10 MPa·m¹ᐟ² |

| Late 20th century | Structural ceramic adoption | Reliable load-bearing use |

This historical trajectory reflects how zirconia ceramic evolved alongside materials science, shifting from empirical observation toward structure-centered understanding.

As understanding deepened, zirconia ceramic shifted from fragile oxide to robust engineering material. Consequently, its crystal structures became the next focal point for explaining performance at a fundamental level.

Crystal Structures of Zirconia Ceramic

Moreover, once zirconia ceramic entered structural materials research, its internal crystal architecture became central to performance interpretation. Therefore, crystal structures explain why this ceramic behaves unlike most oxides under thermal and mechanical stress.

Zirconia ceramic is defined not by a single lattice arrangement but by multiple crystallographic phases. Consequently, understanding phase symmetry, transformation pathways, and associated strain fields is essential for interpreting strength, toughness, and long-term stability.

Historically, failures and successes of zirconia ceramic correlate directly with how these crystal structures evolve under temperature and stress. Accordingly, the following subsections examine each phase and its engineering implications.

Monoclinic tetragonal and cubic phases

At room temperature, zirconia ceramic naturally adopts a monoclinic crystal structure with low symmetry. Quantitatively, this phase exhibits lattice parameters that generate internal anisotropy, resulting in limited atomic slip and low fracture tolerance.

As temperature increases beyond 1170 °C, zirconia transitions to a tetragonal structure with higher symmetry and reduced lattice distortion. Subsequently, above 2370 °C, a fully cubic fluorite-type structure forms, characterized by isotropic atomic spacing and enhanced ionic mobility.

Importantly, each phase possesses distinct mechanical signatures, with monoclinic zirconia showing fracture toughness near 1.5–2.5 MPa·m¹ᐟ², while metastable tetragonal zirconia exhibits significantly higher crack resistance under constrained conditions.

Phase transformation behavior and temperature dependence

Phase transitions in zirconia ceramic are diffusionless and martensitic in nature. Specifically, the tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation occurs rapidly upon cooling, accompanied by volumetric expansion of approximately 4%.

This abrupt volume change generates localized compressive stresses when transformation occurs near a crack front. As a result, crack propagation is impeded through stress shielding, a phenomenon central to zirconia’s transformation toughening behavior.

However, when phase transformation occurs uncontrollably throughout the bulk, internal stresses accumulate uniformly. Consequently, early zirconia ceramic components fractured during cooling rather than in service, highlighting the necessity of phase control.

Volume expansion and transformation mechanics

The volumetric expansion associated with phase transformation represents both the greatest risk and greatest advantage of zirconia ceramic. Measured linear strain values during tetragonal-to-monoclinic conversion range from 1.2–1.6%, depending on grain size and constraint.

In engineered microstructures, transformation is deliberately delayed until stress concentration triggers localized conversion. Thus, energy dissipation occurs precisely where cracks attempt to advance, increasing apparent fracture toughness by up to 300% relative to unstabilized zirconia.

Conversely, if grains exceed critical sizes near 0.8–1.2 μm, spontaneous transformation may occur during thermal cycling. Therefore, crystal structure control becomes inseparable from grain size engineering.

Crystallographic phases and engineering significance of zirconia ceramic

| Crystal Phase | Stability Temperature (°C) | Volume Change (%) | Typical Toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | Engineering Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclinic | < 1170 | Reference | 1.5–2.5 | Brittle, crack-prone |

| Tetragonal | 1170–2370 (metastable at RT) | +4 (on transform) | 6–10 | Transformation toughening |

| Cubic | > 2370 | None | 2–4 | High ionic conductivity |

Control over phase stability therefore becomes the decisive factor that allows zirconia ceramic to operate reliably under extreme conditions.

Stabilized Zirconia Ceramic Systems

Furthermore, after crystal polymorphism clarified the intrinsic instability of pure zirconia ceramic, materials science shifted toward controlled stabilization. Consequently, engineered stabilization systems transformed phase volatility into predictable mechanical behavior suitable for demanding service environments.

Stabilized zirconia ceramic systems rely on deliberate lattice modification rather than compositional replacement. Accordingly, selected dopants alter thermodynamic equilibria, suppressing destructive transformations while preserving beneficial stress-response mechanisms.

Historically, this approach marked the transition from fragile refractory oxide to structurally dependable ceramic. Therefore, understanding stabilized systems is essential for interpreting modern zirconia ceramic performance.

Yttria stabilized zirconia and its material logic

Yttria stabilized zirconia incorporates yttrium oxide additions typically ranging from 2 to 8 mol%, substituting Zr⁴⁺ ions with Y³⁺ ions. This substitution generates oxygen vacancies that reduce lattice strain and stabilize high-symmetry phases at ambient temperature.

Moreover, at 3 mol% Y₂O₃, the material retains a metastable tetragonal phase capable of stress-induced transformation. Experimental measurements show fracture toughness values between 7 and 10 MPa·m¹ᐟ², significantly exceeding unstabilized zirconia.

As a result, yttria stabilized zirconia ceramic combines structural reliability with adaptive toughness, enabling use in cyclic and impact-prone environments where crack arrest is critical.

Partially stabilized zirconia microstructures

Partially stabilized zirconia ceramic systems are engineered to contain multiple phases within a single microstructure. Typically, cubic zirconia grains form a stable matrix while dispersed tetragonal precipitates remain transformable under stress.

Quantitatively, PSZ microstructures often contain 10–30 vol% tetragonal phase embedded within a cubic matrix. This configuration balances dimensional stability with localized transformation toughening.

Consequently, partially stabilized zirconia ceramic exhibits improved resistance to catastrophic fracture, particularly in components subjected to complex multiaxial loading rather than simple bending.

Phase stability and aging phenomena

Despite stabilization, zirconia ceramic systems remain sensitive to long-term environmental exposure. Notably, low-temperature degradation may occur in humid conditions between 65 and 300 °C, driven by gradual tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation.

Empirical studies report surface transformation depths of 5–50 μm after 1000 hours of hydrothermal exposure, depending on grain size and dopant concentration. This process increases surface roughness and reduces flexural strength by up to 20–40% in severe cases.

Therefore, stabilized zirconia ceramic design requires careful optimization of dopant content, grain size, and operating environment to ensure long-term phase integrity.

Stabilized zirconia ceramic systems and performance characteristics

| Stabilization Type | Dopant Content (mol%) | Dominant Phase at RT | Fracture Toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | Aging Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstabilized ZrO₂ | 0 | Monoclinic | 1.5–2.5 | None |

| Y-TZP | 2–3 Y₂O₃ | Metastable tetragonal | 7–10 | Moderate |

| PSZ | 3–8 Y₂O₃ | Cubic + tetragonal | 5–8 | Low |

| Fully stabilized | >8 Y₂O₃ | Cubic | 2–4 | Very low |

Through stabilization, inherent phase instability is transformed into a predictable mechanical advantage rather than a structural liability.

Mechanical Properties of Zirconia Ceramic

Moreover, once stabilization strategies are established, the mechanical response of zirconia ceramic becomes the decisive factor for structural relevance. Therefore, strength, toughness, and wear behavior collectively determine whether this material can outperform conventional technical ceramics.

Zirconia ceramic is frequently described as both strong and damage-tolerant, a combination rarely observed in oxide ceramics. Consequently, its mechanical profile must be interpreted through microstructural interactions rather than single-property metrics.

Historically, these properties explain why zirconia ceramic gained acceptance in load-bearing and cyclic stress environments. Accordingly, the following subsections analyze its defining mechanical characteristics.

Flexural strength and fracture toughness

Flexural strength represents the ability of zirconia ceramic to sustain bending stress without catastrophic failure. Standard test results indicate characteristic flexural strength values ranging from 800 to 1200 MPa for fine-grained yttria-stabilized systems.

Simultaneously, fracture toughness values reach 6–10 MPa·m¹ᐟ², exceeding alumina by a factor of two to three. This enhancement arises from localized phase transformation near crack tips rather than plastic deformation.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic resists crack initiation and propagation more effectively than most oxide ceramics, enabling reliable performance under tensile and bending loads.

Transformation toughening mechanisms

Transformation toughening constitutes the defining mechanical mechanism of zirconia ceramic. When tensile stress concentrates at a crack tip, metastable tetragonal grains undergo stress-induced transformation to the monoclinic phase.

This transformation produces localized volumetric expansion of approximately 4%, generating compressive stresses that oppose crack opening. Experimental observations show crack growth resistance curves increasing by 200–300% compared to non-transforming ceramics.

As a result, zirconia ceramic exhibits rising R-curve behavior, meaning resistance to fracture increases as cracks extend, a property essential for damage tolerance in service.

Wear resistance under cyclic stress

Wear behavior of zirconia ceramic reflects its combination of hardness and toughness. Measured Vickers hardness values typically fall between 11 and 13 GPa, lower than silicon carbide yet significantly higher than metallic alloys.

In sliding and rolling contact tests, zirconia ceramic demonstrates wear rates below 10⁻⁶ mm³/N·m under moderate loads. Importantly, transformation toughening suppresses surface microcracking, reducing debris generation during repeated contact.

Therefore, under cyclic stress conditions, zirconia ceramic maintains dimensional integrity and surface stability, supporting extended service life in mechanically demanding systems.

Mechanical performance characteristics of zirconia ceramic

| Property | Typical Range | Test Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Flexural strength (MPa) | 800–1200 | 4-point bending |

| Fracture toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | 6–10 | Single-edge notch |

| Vickers hardness (GPa) | 11–13 | HV10 |

| Wear rate (mm³/N·m) | ≤ 1×10⁻⁶ | Sliding contact |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 200–210 | Room temperature |

This balance between strength and toughness distinctly separates zirconia ceramic from conventional oxide ceramics.

Thermal Behavior of Zirconia Ceramic

Furthermore, mechanical reliability alone cannot explain the sustained relevance of zirconia ceramic in demanding environments. Therefore, thermal behavior becomes a decisive dimension, especially where temperature gradients, heat cycling, and prolonged exposure govern material survival.

Zirconia ceramic responds to thermal input through coupled mechanisms involving lattice expansion, phase stability, and heat transfer. Consequently, its thermal performance must be evaluated as a system-level interaction rather than an isolated property.

Historically, many early component failures originated from thermal misinterpretation rather than mechanical overload. Accordingly, the following subsections examine how zirconia ceramic behaves under thermal stress.

Thermal expansion and mismatch sensitivity

Thermal expansion of zirconia ceramic is moderate compared with metals but higher than that of alumina. Measured coefficients of thermal expansion typically range from 10.0 to 11.5 ×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹ between room temperature and 1000 °C, depending on stabilization level.

Moreover, when zirconia ceramic interfaces with metallic or composite structures, differential expansion generates interfacial stresses. Empirical strain analyses indicate that mismatch stresses may exceed 150–250 MPa during rapid heating if interface compliance is insufficient.

Consequently, thermal expansion compatibility becomes critical in assemblies, where controlled heating rates and compliant interlayers mitigate stress concentration.

Thermal shock resistance limits

Thermal shock resistance reflects a material’s ability to tolerate abrupt temperature changes without fracture. Zirconia ceramic demonstrates moderate resistance, with critical temperature differentials typically between 200 and 350 °C, depending on geometry and microstructure.

Notably, transformation toughening partially offsets thermal shock damage by arresting crack initiation. Laboratory quench tests reveal strength retention above 70% after repeated thermal cycling within design limits.

However, beyond threshold gradients, accumulated microcracks reduce structural integrity. Therefore, zirconia ceramic performs best under controlled thermal transitions rather than extreme quenching scenarios.

High temperature phase stability

At elevated temperatures, phase stability governs long-term thermal performance. Stabilized zirconia ceramic retains tetragonal or cubic phases up to 1200–1400 °C without structural collapse, provided dopant distribution remains uniform.

Creep deformation3 rates remain low below 1000 °C, typically under 10⁻⁸ s⁻¹ at moderate stress levels. Above this range, grain boundary diffusion accelerates, gradually reducing dimensional precision.

As a result, zirconia ceramic supports extended high-temperature exposure when operating temperatures remain within stabilized phase regimes.

Thermal performance parameters of zirconia ceramic

| Parameter | Typical Range | Temperature Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal expansion coefficient (×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹) | 10.0–11.5 | 25–1000 |

| Critical thermal shock ΔT (°C) | 200–350 | Rapid cooling |

| Maximum stable service temperature (°C) | 1200–1400 | Long-term exposure |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) | 2.0–3.0 | 25–800 |

| Creep rate (s⁻¹) | ≤ 1×10⁻⁸ | < 1000 |

Reliable thermal behavior therefore supports zirconia ceramic performance in environments defined by repeated heating and prolonged temperature exposure.

Electrical and Ionic Characteristics of Zirconia Ceramic

Additionally, beyond mechanical and thermal responses, zirconia ceramic exhibits distinctive electrical and ionic behavior. Therefore, its classification alternates between insulating structural ceramic and functional ionic conductor, depending on composition and temperature.

Zirconia ceramic does not possess a single electrical identity. Instead, its behavior emerges from lattice defects, phase symmetry, and temperature-driven ion mobility. Consequently, clarifying these characteristics prevents frequent misconceptions surrounding conductivity and insulation.

Historically, this dual nature enabled zirconia ceramic to cross boundaries between structural and functional materials. Accordingly, the following subsections analyze its electrical insulation and ionic transport mechanisms.

Electrical insulation behavior

At ambient temperature, zirconia ceramic behaves as a strong electrical insulator. Measured volume resistivity values typically exceed 10¹² Ω·cm, placing it firmly within the insulating ceramic category under standard conditions.

Moreover, dielectric strength measurements often range between 8 and 12 kV/mm, depending on density and grain boundary purity. These values remain stable across wide humidity ranges due to zirconia’s low moisture absorption.

As a result, zirconia ceramic maintains electrical isolation even when subjected to simultaneous mechanical load and elevated temperature, provided operating conditions remain below ionic activation thresholds.

Oxygen ion conductivity in stabilized zirconia

When stabilized with aliovalent oxides, zirconia ceramic exhibits significant oxygen ion conductivity at elevated temperatures. Specifically, oxygen vacancies created by dopants such as yttria enable ion migration through the crystal lattice.

Quantitatively, ionic conductivity values reach 0.01–0.1 S/cm at temperatures above 800 °C, increasing exponentially with temperature. This behavior arises from thermally activated hopping of O²⁻ ions between vacancy sites.

Consequently, stabilized zirconia ceramic functions as a solid electrolyte under high-temperature conditions while remaining electrically insulating at lower temperatures.

Implications for functional and structural overlap

The coexistence of insulation and ionic conduction positions zirconia ceramic uniquely among oxide ceramics. At room temperature, it serves purely structural and insulating roles; however, at elevated temperatures, ionic transport becomes dominant.

Experimental observations show that below 400 °C, electronic conductivity remains negligible, ensuring electrical isolation. Above this threshold, ionic conduction increases without compromising mechanical integrity.

Therefore, zirconia ceramic supports applications requiring both structural stability and controlled ionic behavior, provided temperature domains are clearly defined.

Electrical and ionic properties of zirconia ceramic

| Property | Typical Value | Temperature Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Volume resistivity (Ω·cm) | > 10¹² | 25 |

| Dielectric strength (kV/mm) | 8–12 | 25 |

| Ionic conductivity (S/cm) | 0.01–0.1 | > 800 |

| Activation energy for ion transport (eV) | 0.9–1.1 | 600–1000 |

| Electronic conductivity (S/cm) | < 10⁻⁸ | < 400 |

This temperature-dependent behavior expands functional relevance without compromising the structural role of zirconia ceramic.

Chemical Stability of Zirconia Ceramic

Moreover, after clarifying electrical and ionic behavior, chemical stability becomes essential for evaluating zirconia ceramic in prolonged service environments. Therefore, resistance to chemical attack, corrosion, and reactive media defines its reliability beyond purely physical stresses.

Zirconia ceramic is widely regarded as chemically inert, yet this stability is conditional rather than absolute. Consequently, its performance depends on temperature, chemical species, and microstructural integrity developed during processing.

Historically, many misconceptions arise from treating zirconia ceramic as universally corrosion-proof. Accordingly, a nuanced chemical perspective is required to understand both its strengths and boundaries.

-

Resistance to acids and alkalis

Zirconia ceramic exhibits strong resistance to most inorganic acids and alkalis at ambient conditions. Quantitative corrosion tests show mass loss rates below 0.01 mg/cm²/day in acidic and alkaline solutions below 200 °C, indicating minimal surface degradation.Furthermore, the absence of silica phases prevents glassy corrosion pathways common in aluminosilicate ceramics. As a result, zirconia ceramic maintains surface integrity in chemically aggressive but moderate-temperature environments.

Nevertheless, concentrated hydrofluoric acid and molten alkali salts at elevated temperatures can induce localized attack, highlighting that chemical stability remains environment-specific.

-

Behavior in oxidizing and reducing atmospheres

Under oxidizing atmospheres, zirconia ceramic remains chemically stable up to 1200–1400 °C, with no measurable mass change during prolonged exposure. Oxygen-rich environments do not alter its stoichiometry due to the already fully oxidized Zr⁴⁺ state.Conversely, in strongly reducing atmospheres at temperatures exceeding 900 °C, partial oxygen loss may occur near surfaces. Experimental observations indicate slight increases in oxygen vacancy concentration without structural collapse.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic tolerates a wide range of redox conditions, provided extreme reduction is avoided over long durations.

-

Interaction with molten metals and reactive media

Contact with molten metals presents a distinct chemical challenge. Zirconia ceramic demonstrates excellent non-wettability toward aluminum, copper, and steel melts, with contact angles often exceeding 120°, limiting chemical infiltration.However, prolonged exposure to molten magnesium or titanium alloys at temperatures above 800 °C may promote interfacial reactions. Measured reaction layer thicknesses typically remain below 10 μm after several hours of exposure.

Therefore, zirconia ceramic functions effectively as a chemically stable barrier in most molten metal environments, subject to controlled exposure time and alloy selection.

-

Long-term corrosion kinetics and surface evolution

Over extended service periods, chemical stability is governed by slow diffusion-controlled processes. Surface roughness increases of <0.5 μm Ra after 1000 hours of exposure have been reported in aggressive aqueous environments.Such gradual evolution does not compromise bulk mechanical properties but may influence surface-sensitive applications. Consequently, surface finishing and grain boundary purity play important roles in chemical longevity.

Ultimately, zirconia ceramic demonstrates predictable, low-rate chemical interaction rather than abrupt degradation.

Chemical resistance characteristics of zirconia ceramic

| Environment | Temperature Range (°C) | Corrosion Rate (mg/cm²/day) | Structural Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic acids | < 200 | < 0.01 | Negligible |

| Alkaline solutions | < 200 | < 0.01 | Negligible |

| Oxidizing atmosphere | < 1400 | ~0 | None |

| Reducing atmosphere | 900–1200 | < 0.05 | Surface-limited |

| Molten metals | 700–900 | < 0.02 | Interfacial only |

Such chemical stability complements mechanical and thermal performance, enabling consistent behavior in chemically aggressive environments.

Processing Routes of Zirconia Ceramic

Subsequently, once chemical stability is established, attention turns toward how zirconia ceramic is transformed from mineral-derived powder into dense engineering components. Therefore, processing routes determine whether intrinsic material potential is fully realized or structurally compromised.

Zirconia ceramic performance is not solely dictated by composition but by the precision of each processing step. Consequently, powder synthesis, shaping, and sintering collectively govern density, grain size, and phase distribution.

Historically, inconsistent processing rather than material limitation accounted for many early failures. Accordingly, the following sections describe how controlled processing enables reproducible zirconia ceramic behavior.

Powder synthesis and particle control

Zirconia ceramic processing begins with powder synthesis, where particle size and purity define downstream behavior. Common synthesis methods produce powders with mean particle sizes between 20 and 80 nm, enabling high sinterability.

Moreover, narrow particle size distributions reduce differential shrinkage during densification. Empirical observations show that agglomerates exceeding 1 μm increase residual porosity by more than 15% after sintering.

As a result, advanced powder conditioning focuses on deagglomeration and surface chemistry control to preserve uniform packing density.

Shaping forming and green body behavior

Shaping converts zirconia ceramic powder into a coherent green body prior to densification. Typical forming methods achieve green densities ranging from 45 to 60% of theoretical density, depending on pressure and binder content.

Additionally, binder distribution influences crack initiation during debinding. Thermal analysis indicates that uneven binder burnout can generate internal stresses exceeding 30 MPa, sufficient to nucleate microcracks.

Consequently, forming uniformity and controlled debinding schedules are essential to maintain structural continuity before sintering.

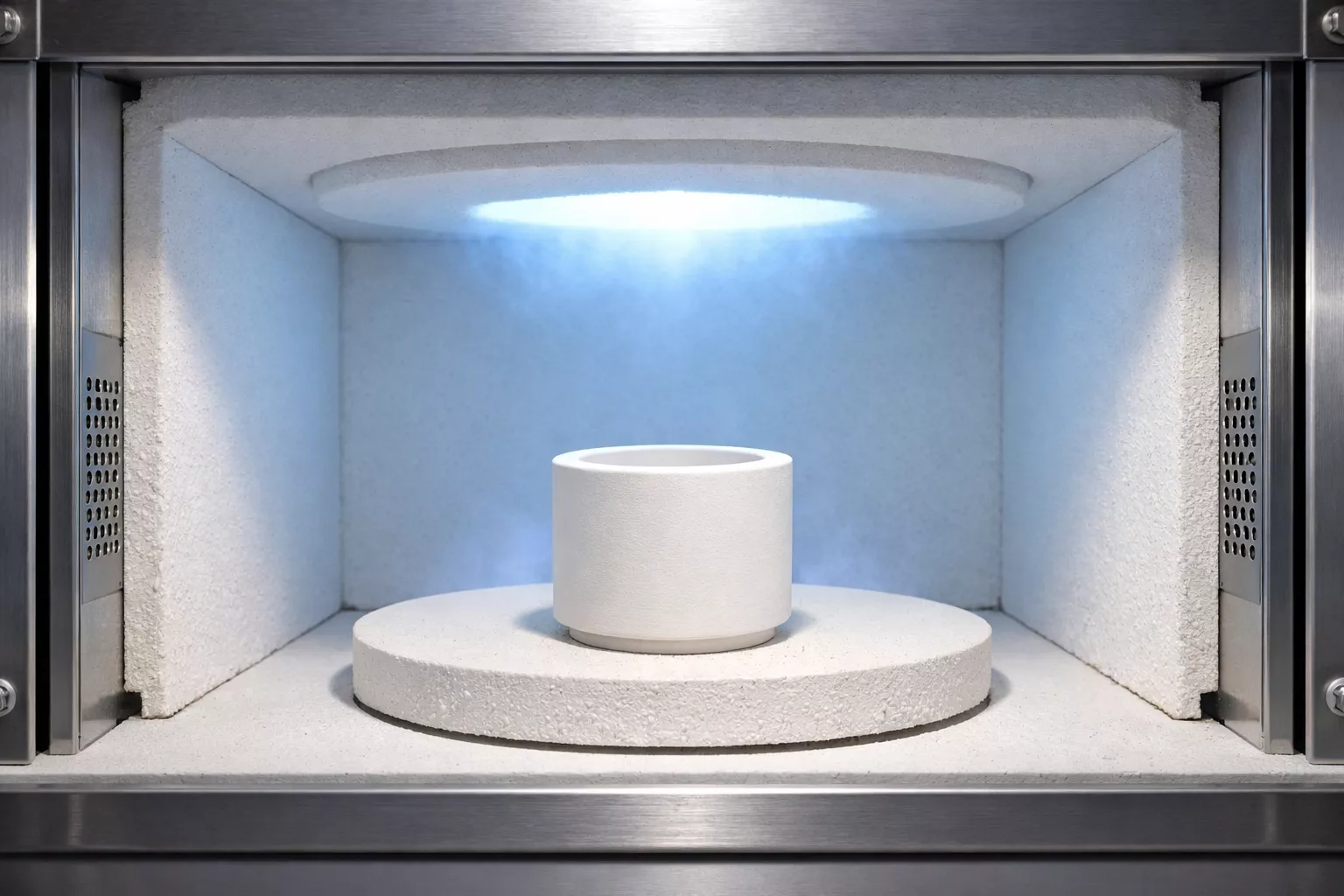

Sintering densification and grain growth

Sintering consolidates zirconia ceramic into a dense polycrystalline solid through diffusion-driven mechanisms. Full densification typically occurs between 1350 and 1550 °C, depending on dopant chemistry and particle size.

However, excessive dwell time promotes grain growth beyond 1 μm, increasing susceptibility to spontaneous phase transformation. Controlled sintering profiles maintain grain sizes near 0.3–0.6 μm, balancing density and phase stability.

Therefore, sintering represents the most critical stage where mechanical, thermal, and aging behavior converge.

Processing parameters influencing zirconia ceramic microstructure

| Processing Stage | Key Parameter | Typical Range | Structural Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powder synthesis | Particle size (nm) | 20–80 | High sinterability |

| Powder conditioning | Agglomerate size (μm) | < 1 | Uniform packing |

| Green forming | Green density (%) | 45–60 | Reduced shrinkage |

| Sintering | Temperature (°C) | 1350–1550 | Full densification |

| Sintering | Grain size (μm) | 0.3–0.6 | Phase stability |

Zirconia ceramic reliability emerges only when powder preparation, forming, and sintering are coherently optimized as a single system.

Microstructural Engineering of Zirconia Ceramic

Moreover, after processing routes establish density and phase constitution, microstructural engineering determines how zirconia ceramic responds under real service stresses. Therefore, grain size, defect population, and surface condition collectively define whether the material performs reliably or degrades prematurely.

Zirconia ceramic does not fail because of its chemistry but because of microstructural imbalance. Consequently, engineering the internal architecture becomes as critical as selecting the correct stabilization system.

Historically, long-term performance variations among seemingly identical components can be traced to subtle microstructural differences. Accordingly, the following sections examine how microstructure governs strength, aging, and failure resistance.

Grain size effects on toughness and aging

Grain size directly influences both fracture toughness and phase stability in zirconia ceramic. Fine-grained microstructures with average grain sizes between 0.2 and 0.6 μm maximize transformation toughening while suppressing spontaneous phase change.

Furthermore, experimental aging studies demonstrate that grain sizes exceeding 0.8 μm accelerate low-temperature degradation rates by up to 3× under humid exposure. This occurs because larger grains reduce the energy barrier for tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation.

As a result, tight grain size control remains a primary design criterion for achieving balanced toughness and long-term stability.

Porosity and defect sensitivity

Residual porosity acts as a dominant stress concentrator within zirconia ceramic. Even porosity levels as low as 0.5–1.0 vol% can reduce flexural strength by more than 20%, according to fracture mechanics analysis.

Moreover, interconnected pores facilitate moisture ingress, promoting localized phase transformation during aging. Microscopic evaluation often reveals crack initiation at pore clusters rather than grain boundaries.

Consequently, achieving near-theoretical density above 99.5% is essential for maintaining mechanical reliability and environmental resistance.

Surface condition and stress concentration

Surface condition critically influences zirconia ceramic performance under tensile and cyclic loading. Machining-induced flaws with depths of 5–20 μm can significantly reduce strength if left unmitigated.

However, controlled surface finishing reduces flaw depth below 2 μm, restoring more than 85% of intrinsic strength. Polishing also delays surface-initiated aging by limiting water-assisted phase transformation.

Therefore, surface engineering represents the final microstructural safeguard against premature failure in service.

Microstructural parameters and performance relationships in zirconia ceramic

| Microstructural Feature | Typical Range | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Grain size (μm) | 0.2–0.6 | Optimal toughness and stability |

| Critical grain size (μm) | > 0.8 | Increased aging risk |

| Residual porosity (vol%) | < 0.5 | Strength retention |

| Relative density (%) | > 99.5 | Environmental resistance |

| Surface flaw depth (μm) | < 2 | High tensile reliability |

Control over grains, pores, and surface conditions ensures property stability throughout the service life of zirconia ceramic.

Industrial Relevance of Zirconia Ceramic

Moreover, after microstructural engineering defines intrinsic reliability, industrial relevance emerges from how zirconia ceramic performs within complex operating systems. Therefore, its value is realized where mechanical stress, thermal exposure, and chemical interaction converge over extended service periods.

Zirconia ceramic does not function as an isolated material in industry but as an integrated component within assemblies and process environments. Consequently, its relevance depends on predictable behavior under continuous operation rather than peak property values alone.

Historically, adoption followed repeated confirmation that engineered zirconia ceramic sustains performance where conventional materials exhibit accelerated degradation. Accordingly, the following sections examine representative industrial contexts shaped by these demands.

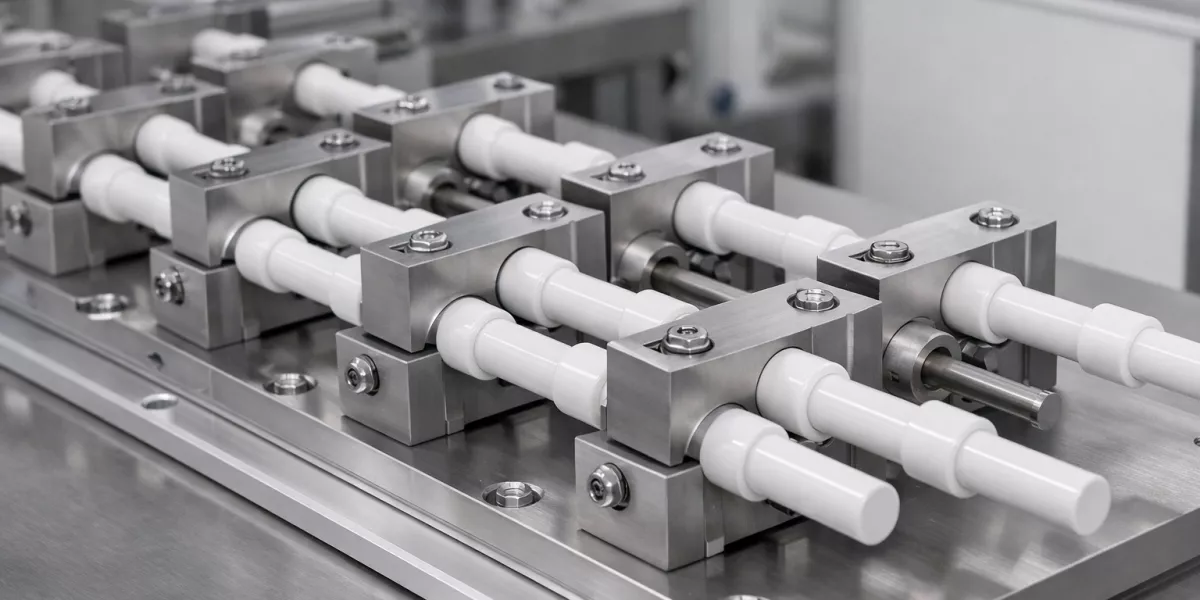

Zirconia ceramic in wear intensive systems

Wear-intensive systems impose persistent contact stress, abrasive interaction, and cyclic loading on material surfaces. In such environments, zirconia ceramic demonstrates stable wear behavior due to its combination of hardness and transformation-induced crack resistance.

Quantitative tribological testing shows volume wear rates below 1 × 10⁻⁶ mm³/N·m under dry sliding conditions at contact pressures exceeding 300 MPa. Moreover, surface integrity remains stable because stress-induced phase transformation suppresses microcrack coalescence.

As a result, zirconia ceramic maintains dimensional accuracy and surface continuity in systems characterized by repeated mechanical interaction rather than single-event overload.

Zirconia ceramic in sealing and flow control

Sealing and flow control applications require simultaneous resistance to wear, chemical exposure, and contact stress. Zirconia ceramic responds favorably due to its dense microstructure and low reactivity with common process media.

Measured leakage stability remains consistent across 10⁶–10⁷ contact cycles when surface roughness is controlled below 0.05 μm Ra. Additionally, compressive strength exceeding 2000 MPa prevents plastic deformation at sealing interfaces.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic supports long-term sealing integrity where dimensional stability and surface durability are essential.

Zirconia ceramic in continuous operation environments

Continuous operation environments prioritize predictable degradation rates over absolute strength. Zirconia ceramic exhibits slow, diffusion-controlled aging with property retention exceeding 85–90% after 10,000 hours under moderate thermal and chemical exposure.

Furthermore, low creep rates below 10⁻⁸ s⁻¹ at temperatures under 1000 °C ensure geometric stability during prolonged service. These characteristics reduce the likelihood of sudden performance loss during uninterrupted operation.

Therefore, zirconia ceramic aligns with systems designed for sustained duty cycles rather than intermittent use.

Performance characteristics of zirconia ceramic in industrial environments

| Operating Context | Dominant Stress Type | Typical Quantitative Indicator | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wear-intensive systems | Abrasion and contact stress | Wear rate ≤ 1×10⁻⁶ mm³/N·m | Dimensional stability |

| Sealing and flow control | Contact pressure and corrosion | Surface roughness < 0.05 μm Ra | Leakage consistency |

| Continuous operation | Thermal and chemical exposure | Property retention ≥ 85% | Long service life |

| Cyclic mechanical loading | Repeated stress | > 10⁶ load cycles | Crack resistance |

| Elevated temperature service | Thermal creep | Creep rate < 10⁻⁸ s⁻¹ | Shape retention |

Suitability for demanding systems arises from the convergence of mechanical resilience, chemical stability, and controlled degradation behavior.

Comparison Between Zirconia Ceramic and Other Technical Ceramics

Subsequently, after establishing industrial relevance, comparative evaluation clarifies where zirconia ceramic stands among advanced ceramic materials. Therefore, contrast with other technical ceramics highlights performance trade-offs rather than absolute superiority.

Zirconia ceramic is often discussed alongside alumina, silicon carbide, and silicon nitride because these materials occupy overlapping engineering domains. However, their intrinsic property balances differ significantly, shaping distinct suitability boundaries.

Historically, material substitution decisions reflect tolerance for brittleness, thermal load, and wear mechanisms rather than single-property optimization. Accordingly, the following comparisons focus on structural behavior, thermal response, and durability.

-

Zirconia ceramic versus alumina ceramic

Zirconia ceramic exhibits markedly higher fracture toughness, typically 6–10 MPa·m¹ᐟ², compared with alumina’s 3–4 MPa·m¹ᐟ². This difference results in improved resistance to catastrophic cracking under tensile stress.Conversely, alumina offers lower thermal expansion coefficients near 8 ×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹, enhancing compatibility in rigid assemblies. Consequently, zirconia ceramic is favored where toughness dominates, while alumina excels in dimensionally constrained thermal environments.

Therefore, selection depends on failure mode tolerance rather than maximum strength alone.

-

Zirconia ceramic versus silicon carbide

Silicon carbide demonstrates superior hardness exceeding 25 GPa and thermal conductivity above 100 W/m·K, enabling exceptional abrasion resistance and heat dissipation.However, silicon carbide fracture toughness typically remains below 4 MPa·m¹ᐟ², limiting crack tolerance under impact or misalignment. In contrast, zirconia ceramic sacrifices hardness for significantly enhanced damage tolerance.

As a result, zirconia ceramic becomes advantageous where impact resistance and crack arrest outweigh extreme wear resistance.

-

Zirconia ceramic versus silicon nitride

Silicon nitride combines moderate toughness around 5–7 MPa·m¹ᐟ² with low density near 3.2 g/cm³, offering high strength-to-weight ratios.Zirconia ceramic, with density near 6.0 g/cm³, provides greater compressive strength and superior transformation toughening. Consequently, zirconia ceramic favors compressive and sealing-dominated systems, whereas silicon nitride suits high-speed rotational components.

Thus, microstructural design priorities dictate material preference.

-

Durability and aging considerations across ceramics

Long-term durability varies across ceramic families. Zirconia ceramic may experience hydrothermal aging under specific conditions, while alumina and silicon carbide exhibit negligible phase instability.However, controlled zirconia ceramic systems retain more than 85% of mechanical properties over extended exposure when grain size and dopant levels are optimized. Therefore, aging sensitivity is manageable rather than prohibitive.

Ultimately, durability must be assessed in relation to operating environment rather than inherent material class.

Comparative properties of major technical ceramics

| Material | Fracture Toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | Thermal Expansion (×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹) | Hardness (GPa) | Density (g/cm³) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zirconia ceramic | 6–10 | 10.0–11.5 | 11–13 | ~6.0 |

| Alumina ceramic | 3–4 | 7.5–8.5 | 15–20 | ~3.9 |

| Silicon carbide | 3–4 | 4.0–4.5 | 25–28 | ~3.2 |

| Silicon nitride | 5–7 | 3.0–3.5 | 14–16 | ~3.2 |

Understanding these contrasts supports material selection based on failure mechanisms rather than isolated property rankings.

Limitations and Failure Mechanisms of Zirconia Ceramic

Nevertheless, despite its favorable balance of toughness and stability, zirconia ceramic is not immune to intrinsic limitations. Therefore, recognizing its failure mechanisms is essential for interpreting performance boundaries rather than assuming universal suitability.

Zirconia ceramic failures rarely arise from a single cause. Instead, they emerge from the interaction between phase behavior, microstructure, environment, and stress history. Consequently, limitation analysis must address coupled mechanisms rather than isolated defects.

Historically, many unexpected failures occurred where zirconia ceramic was applied beyond its stability envelope. Accordingly, the following aspects outline its principal vulnerability domains.

-

Low-temperature degradation and phase instability

Low-temperature degradation involves gradual tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation in the presence of moisture. Experimental exposure studies show surface transformation depths of 10–50 μm after 1000–3000 hours at temperatures between 65 and 300 °C.This transformation increases surface roughness and induces microcracking, leading to flexural strength reductions of up to 30–40% in severe conditions. However, bulk properties remain largely intact during early stages.

Therefore, this mechanism represents a surface-driven aging process rather than catastrophic bulk failure.

-

Thermal mismatch and constraint-induced cracking

Zirconia ceramic exhibits relatively high thermal expansion compared with other ceramics. When constrained within rigid assemblies, thermal cycling can generate tensile stresses exceeding 200 MPa at interfaces.Finite element simulations indicate that repeated mismatch stress accumulation accelerates microcrack initiation at edges and contact zones. These cracks may propagate under cyclic thermal loading even when peak temperatures remain moderate.

Consequently, constraint management is critical wherever zirconia ceramic interfaces with materials of lower expansion coefficients.

-

Grain growth–induced instability

Excessive grain growth compromises phase stability by lowering the critical stress required for spontaneous transformation. Microstructures with grain sizes exceeding 1.0 μm demonstrate significantly increased transformation rates during thermal cycling.Mechanical testing reveals corresponding reductions in fracture toughness by 20–25%, undermining transformation toughening benefits. This degradation is gradual but irreversible once grain growth occurs.

Thus, sintering and thermal exposure histories directly influence long-term reliability.

-

Surface flaw amplification under tensile stress

Like all ceramics, zirconia ceramic remains sensitive to surface flaws under tensile loading. Flaws deeper than 10 μm can reduce tensile strength by more than 35%, particularly under dynamic loading conditions.While transformation toughening delays crack growth, it cannot eliminate stress concentration entirely. Consequently, surface integrity remains a governing factor in tensile-dominated applications.

Ultimately, flaw control determines whether theoretical toughness translates into practical durability.

Failure mechanisms and critical thresholds in zirconia ceramic

| Failure Mechanism | Trigger Condition | Quantitative Threshold | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-temperature degradation | Moisture + 65–300 °C | 10–50 μm surface transformation | Strength loss up to 40% |

| Thermal mismatch cracking | Rigid constraint | > 200 MPa interfacial stress | Edge cracking |

| Grain growth instability | Grain size > 1.0 μm | Toughness −20–25% | Reduced crack resistance |

| Surface flaw propagation | Flaw depth > 10 μm | Tensile stress concentration | Premature failure |

Understanding these failure mechanisms allows zirconia ceramic to be applied within clearly defined and rational boundaries.

Environmental and Long Term Behavior of Zirconia Ceramic

Subsequently, after clarifying failure mechanisms, long-term behavior under real environmental exposure becomes the decisive lens for assessing zirconia ceramic durability. Therefore, time-dependent evolution rather than initial performance determines service reliability.

Zirconia ceramic interacts continuously with its surroundings through thermal cycles, moisture ingress, and chemical exposure. Consequently, long-term behavior reflects cumulative microstructural changes rather than abrupt material degradation.

Historically, discrepancies between laboratory strength data and field performance often originated from overlooked environmental effects. Accordingly, the following discussion addresses how zirconia ceramic evolves over extended operational timelines.

-

Hydrothermal exposure and surface evolution

In humid environments, zirconia ceramic may undergo progressive surface transformation driven by water-assisted diffusion. Long-duration studies report monoclinic phase fractions increasing by 5–15% within surface layers after 2000–5000 hours at temperatures between 80 and 250 °C.This transformation produces microcrack networks confined to shallow depths, typically below 50 μm. While bulk mechanical properties remain stable, surface-sensitive functions may experience gradual performance drift.

Therefore, hydrothermal exposure primarily influences surface integrity rather than structural collapse.

-

Thermal cycling and fatigue accumulation

Repeated thermal cycling induces cyclic stress even when peak temperatures remain within design limits. Experimental fatigue tests involving 10⁴–10⁵ heating and cooling cycles demonstrate stiffness reductions below 10%, indicating gradual but controlled degradation.Importantly, transformation toughening mitigates crack growth during early fatigue stages. However, accumulated microcracks may coalesce over prolonged cycles, particularly near geometric discontinuities.

Consequently, thermal fatigue4 resistance depends on component geometry and temperature ramp rates rather than material composition alone.

-

Chemical environment persistence

Long-term chemical exposure typically results in diffusion-limited reactions rather than aggressive corrosion. Mass change measurements remain below 0.1 mg/cm² after 3000 hours in moderately aggressive aqueous environments.Such slow kinetics ensure predictable behavior over extended durations. As a result, zirconia ceramic retains chemical integrity provided environmental conditions remain within established stability windows.

Ultimately, chemical persistence complements mechanical and thermal resilience.

-

Dimensional stability over time

Dimensional stability under long-term load is governed by creep and stress relaxation mechanisms. At temperatures below 900 °C, measured creep strain remains under 0.1% after 10,000 hours under moderate compressive stress.This stability preserves geometric precision in continuous operation systems. Therefore, zirconia ceramic supports long service intervals without recalibration or structural compensation.

Overall, dimensional changes remain gradual and predictable.

Long-term environmental response of zirconia ceramic

| Environmental Factor | Exposure Condition | Time Scale | Observed Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture and humidity | 80–250 °C | 2000–5000 h | Surface phase transformation |

| Thermal cycling | ΔT within design limit | 10⁴–10⁵ cycles | < 10% stiffness reduction |

| Chemical exposure | Aqueous aggressive media | ~3000 h | Mass change < 0.1 mg/cm² |

| Sustained thermal load | < 900 °C | 10,000 h | Creep strain < 0.1% |

Predictable environmental response enables zirconia ceramic to function reliably across extended service lifetimes.

Why Zirconia Ceramic Continues to Attract Industrial Attention

Ultimately, after examining intrinsic properties, processing logic, microstructural control, and long-term behavior, broader patterns of industrial attention become evident. Therefore, continued interest in zirconia ceramic reflects convergence between material capabilities and evolving system requirements.

Zirconia ceramic attracts attention not because it excels in a single parameter, but because it balances competing demands. Consequently, it aligns with environments where failure tolerance, predictability, and durability outweigh absolute extremes.

Historically, materials that persist across decades do so by accommodating uncertainty. Accordingly, zirconia ceramic remains relevant where operating conditions fluctuate and safety margins must be preserved.

-

Tolerance to complex stress states

Industrial systems increasingly operate under combined mechanical, thermal, and chemical stresses. Zirconia ceramic accommodates these conditions through transformation toughening and stable microstructural response.Quantitative service data indicate crack resistance retention above 85% under mixed loading scenarios involving compression, sliding, and thermal gradients. This tolerance reduces sensitivity to localized overload events.

As a result, zirconia ceramic supports systems where stress states cannot be fully isolated or simplified.

-

Predictable degradation rather than sudden failure

Materials that fail abruptly impose high operational risk. Zirconia ceramic, by contrast, exhibits gradual performance evolution driven by surface-level mechanisms.Measured property decline rates typically remain below 1–2% per 1000 hours under controlled environments. This predictability enables long-term planning and monitoring.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic aligns with reliability-focused engineering philosophies.

-

Compatibility with precision engineering trends

Modern systems emphasize dimensional stability and surface integrity over brute strength. Zirconia ceramic offers elastic modulus consistency near 200 GPa and minimal creep under service temperatures below 900 °C.Such characteristics support precision assemblies where alignment and sealing accuracy are critical. Therefore, zirconia ceramic integrates naturally with high-precision design approaches.

Ultimately, compatibility with precision requirements sustains its relevance.

-

Material system maturity and knowledge depth

Zirconia ceramic benefits from decades of accumulated experimental and industrial knowledge. Failure modes, processing sensitivities, and stabilization strategies are well characterized.This maturity reduces uncertainty during system design and validation. As a result, zirconia ceramic transitions from experimental material to dependable engineering choice.

In essence, accumulated understanding amplifies material value.

Drivers sustaining industrial interest in zirconia ceramic

| Driver | Quantitative Indicator | Long-Term Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Stress tolerance | ≥ 85% crack resistance retention | Reduced failure risk |

| Degradation predictability | 1–2% property loss per 1000 h | Maintenance planning |

| Dimensional stability | Creep < 0.1% at < 900 °C | Precision retention |

| Knowledge maturity | > 50 years of research | Design confidence |

This balance explains why zirconia ceramic persists as a foundational material in demanding engineered systems.

Conclusion

Zirconia ceramic evolves from natural oxide to engineered system material through controlled structure, stability, and predictable behavior.

For applications requiring durability under combined stress conditions, zirconia ceramic warrants detailed technical evaluation within system-specific boundaries.

FAQ

What makes zirconia ceramic different from other ceramics?

Its transformation toughening mechanism provides exceptional crack resistance.

Does zirconia ceramic degrade over time?

Yes, but degradation is gradual and surface-limited under controlled environments.

Is zirconia ceramic suitable for long-term operation?

Predictable aging and low creep support extended service life.

Why is zirconia ceramic still widely researched?

Its balanced performance and mature knowledge base sustain ongoing relevance.

References:

-

This concept explains thermodynamic stability and is widely used to assess oxide formation and persistence in natural environments. ↩

-

This mechanical property measures resistance to crack propagation and is fundamental to evaluating structural ceramics. ↩

-

This time-dependent deformation mechanism governs dimensional stability at elevated temperatures. ↩

-

This mechanism describes damage accumulation under repeated temperature cycling. ↩