Poor sintering consistency often originates not from furnace failure, but from improper crucible use that silently distorts thermal balance and shrinkage behavior.

This article consolidates process-level knowledge around zirconia sintering crucible use, linking preparation, loading, and parameter control into a coherent operational framework that stabilizes output quality while reducing corrective iterations.

Accordingly, the discussion progresses from pre-use conditions toward loading mechanics and thermal coordination, forming a structured pathway that mirrors real industrial sintering workflows.

In practical sintering workflows, stable outcomes depend first on whether the crucible itself is operated within its intended physical and thermal boundaries.

Correct Use Conditions Before Loading Zirconia Parts

Before any zirconia components are introduced, the crucible itself must be evaluated as an active thermal element rather than a passive container. Moreover, initial condition, stabilization behavior, and handling discipline collectively influence early densification uniformity and dimensional repeatability. Consequently, overlooking pre-use conditions often leads to variability that cannot be corrected through later parameter adjustment.

Initial Condition of a New Zirconia Sintering Crucible

A newly manufactured zirconia sintering crucible typically exits final firing at temperatures exceeding 1,600 °C, achieving bulk densities above 6.0 g/cm³ with open porosity below 0.5%. However, residual thermal gradients and microstructural relaxation remain present despite full sintering.

In practice, early production runs have shown that untreated crucibles may exhibit dimensional drift of 0.05–0.12 mm across the first 2–3 thermal cycles, particularly along the flat base where thermal mass is highest. As a result, placing precision zirconia parts directly into a new crucible can transfer this transient instability into the product.

Therefore, initial stabilization cycles are recommended to allow the crucible’s internal stress state and heat flow characteristics to equilibrate before contact with production components.

Preheating and Stabilization Requirements

Preheating is not intended to increase strength but to normalize thermal response. Typically, an empty crucible is heated to 1,200–1,300 °C at a controlled rate of 5–8 °C/min, followed by a dwell of 30–60 minutes. Subsequently, slow cooling below 300 °C minimizes thermal shock accumulation.

Field observations indicate that crucibles receiving at least one dedicated stabilization cycle demonstrate temperature lag reductions of 15–20% between furnace setpoint and crucible interior. Consequently, heat transfer during actual sintering becomes more predictable.

In such cases, subsequent production runs show narrower shrinkage dispersion, often reduced from ±0.25% to ±0.12%, which directly improves dimensional reliability.

Environmental Cleanliness and Handling Practices

Handling conditions prior to loading exert a subtler but measurable influence. Zirconia surfaces readily retain fine particulates, oils, or moisture films introduced during manual transfer. Although invisible, these contaminants alter local emissivity and contact resistance.

Laboratory data reveal that surface contamination layers as thin as 5–10 µm can create localized temperature deviations exceeding 8 °C during ramp-up. Accordingly, crucibles should be handled with powder-free gloves and stored in environments below 60% relative humidity.

Most importantly, placing crucibles directly onto metallic benches or abrasive surfaces should be avoided, because micro-scratching at the flat base increases frictional constraint during shrinkage.

Pre-Use Condition Summary

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Initial stabilization cycles (count) | 1–2 | Reduces early dimensional drift |

| Preheat temperature (°C) | 1,200–1,300 | Normalizes thermal response |

| Heating rate (°C/min) | 5–8 | Limits stress accumulation |

| Dwell time (min) | 30–60 | Improves internal equilibration |

| Surface contamination thickness (µm) | <5 | Prevents local thermal deviation |

| Storage humidity (%) | <60 | Limits moisture adsorption |

Once baseline operating conditions are established, attention naturally shifts to how zirconia components are arranged within the crucible during loading.

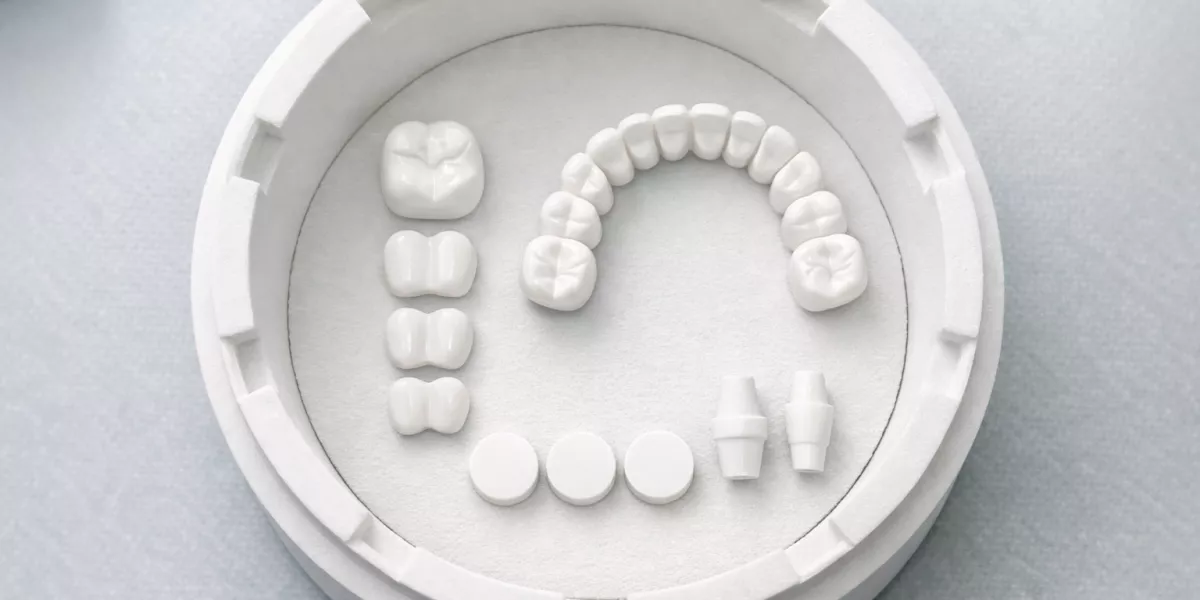

Loading Geometry Inside a Zirconia Sintering Crucible

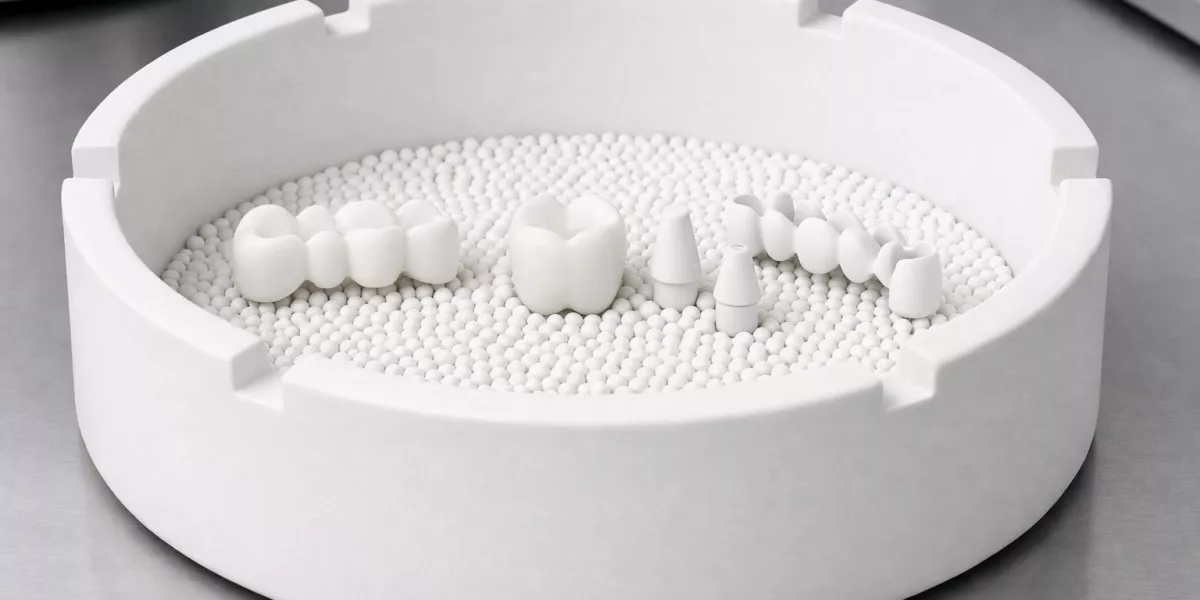

Loading geometry represents one of the most underestimated variables in zirconia sintering crucible use. However, spatial relationships between the crucible base, rim notches, and zirconia components strongly influence thermal gradients and mechanical constraint. Consequently, even with identical furnace parameters, improper loading can produce divergent densification outcomes.

Positioning Relative to the Flat Crucible Base

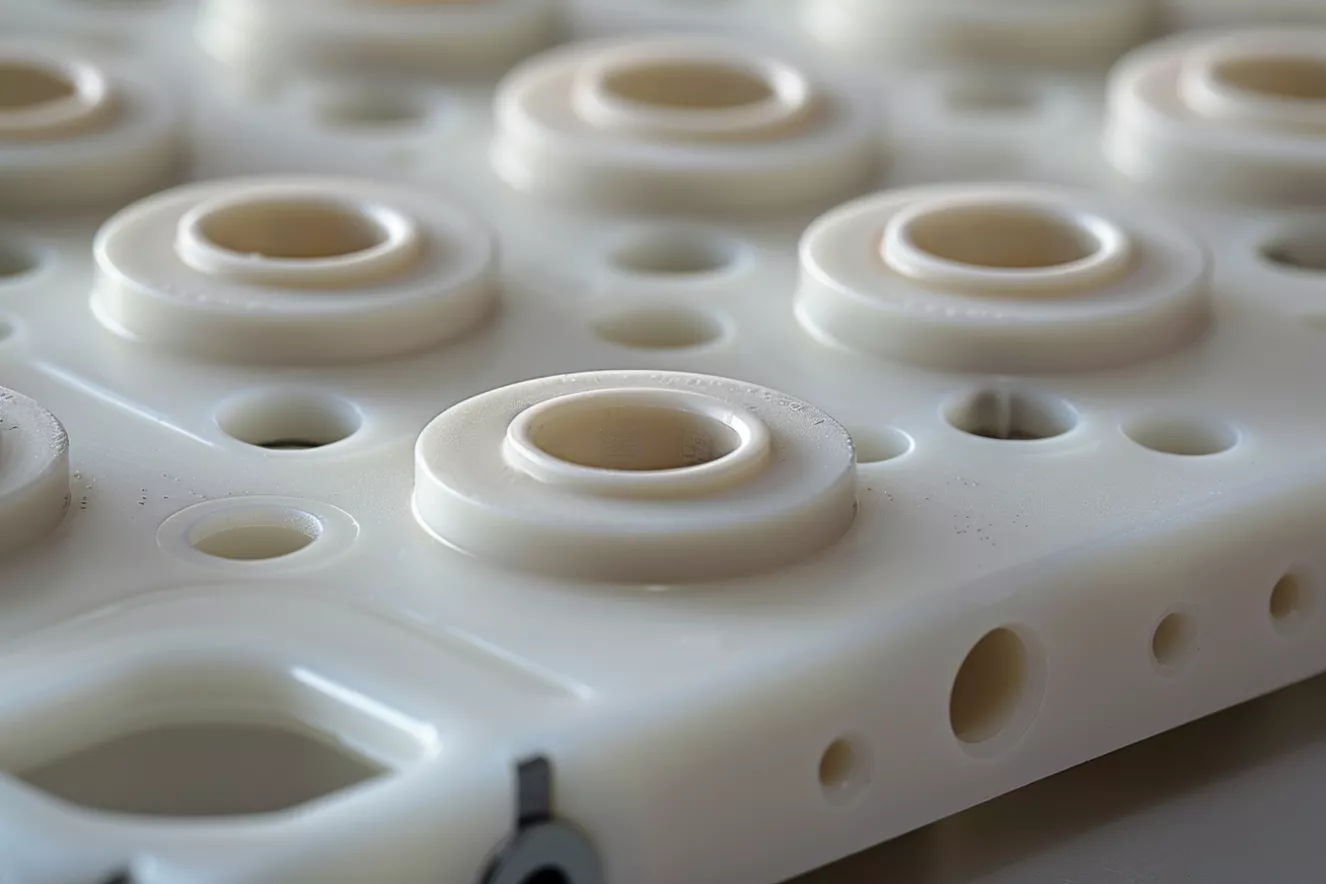

The flat base of a zirconia sintering crucible establishes the primary mechanical interface during heating and shrinkage. Ideally, zirconia parts should rest on support elements that allow planar contact without rigid constraint, enabling isotropic contraction during densification.

Experimental observations show that direct full-surface contact between zirconia components and the crucible base can increase frictional resistance by 30–45%, especially above 1,100 °C where viscous flow initiates. As a result, constrained regions often exhibit delayed densification and localized tensile stress accumulation.

Therefore, controlled separation using ceramic beads or setters with contact areas below 5–8% of the part footprint significantly improves dimensional uniformity.

Interaction With Rim Notches and Support Elements

Rim notches are not passive features; instead, they function as thermal and mechanical modulation points. When zirconia components or support frames interact asymmetrically with these notches, uneven heat exchange and airflow disturbance may occur.

In documented sintering cycles, asymmetric engagement with rim notches produced lateral temperature deviations of up to 12 °C across the crucible interior. Consequently, parts positioned closer to notch zones often reached peak densification earlier than centrally located counterparts.

To mitigate this effect, loading patterns should preserve radial symmetry, ensuring that no critical component edge aligns exclusively with a single notch. Balanced placement distributes convective and radiative influences more evenly.

Spacing Rules Between Zirconia Components

Adequate spacing between zirconia parts is essential to avoid mutual thermal shielding and shrinkage interference. When components are positioned too closely, localized heat accumulation may accelerate grain growth and distort shrinkage trajectories.

Measurements indicate that maintaining a minimum clearance of 3–5 mm between adjacent zirconia components reduces peak temperature differentials by approximately 18%. Moreover, sufficient spacing allows free radial contraction, preventing edge-to-edge constraint during the final sintering stage.

Accordingly, dense stacking strategies aimed at throughput maximization often compromise geometric accuracy and should be evaluated against acceptable tolerance limits.

Loading Geometry Summary

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Contact area ratio (%) | <8 | Reduces frictional constraint |

| Minimum part spacing (mm) | 3–5 | Limits thermal shielding |

| Radial symmetry deviation (°) | <10 | Improves densification balance |

| Temperature deviation near notches (°C) | <5 | Ensures uniform heat exposure |

| Support contact points (count) | 3–5 | Maintains mechanical stability |

With loading geometry defined, the applied temperature profile becomes the primary variable governing densification behavior and dimensional stability.

Temperature Profiles Applied With Zirconia Sintering Crucibles

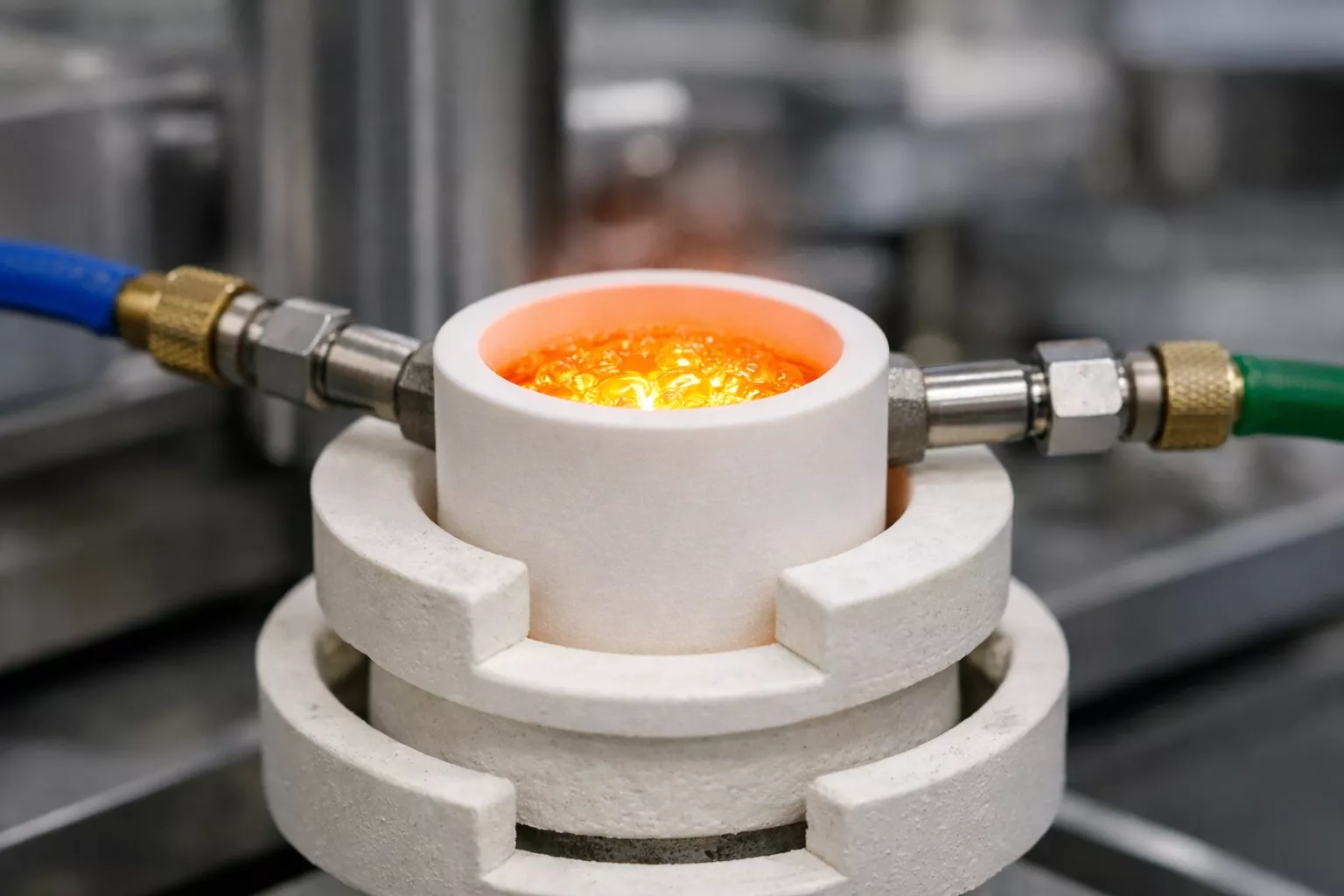

Temperature programming cannot be treated independently from zirconia sintering crucible use. Moreover, crucible wall thickness, thermal mass, and internal geometry reshape heating and cooling dynamics relative to empty-chamber calibration. Consequently, parameter values that perform well without a crucible often require systematic adaptation once a crucible is introduced.

Heating Rate Sensitivity Related to Crucible Mass

Zirconia sintering crucibles typically exhibit wall thicknesses exceeding 6–10 mm, producing a thermal mass substantially higher than that of zirconia parts alone. As a result, heat absorption by the crucible delays internal temperature rise during ramp-up stages.

Instrumented trials demonstrate that when furnace heating rates exceed 10 °C/min, internal crucible temperatures may lag setpoints by 20–35 °C above 900 °C. Consequently, zirconia parts experience non-uniform heating, particularly during binder burnout and early-stage diffusion.

Therefore, controlled heating rates between 3–7 °C/min are generally preferred to synchronize furnace output with crucible-mediated heat transfer.

Dwell Time and Thermal Equalization

Dwell periods serve not only material diffusion but also thermal equalization across the crucible–load system. Without adequate dwell, the crucible interior may never fully equilibrate with the furnace atmosphere.

Data collected from repeated cycles indicate that extending high-temperature dwell time from 60 minutes to 120 minutes reduces internal temperature gradients by approximately 40%. As a consequence, densification progresses more uniformly across all parts within the crucible.

In particular, flat-bottom crucibles benefit from longer dwell phases, because heat must penetrate through both sidewalls and the base to reach equilibrium.

Cooling Rate and Structural Relaxation

Cooling behavior exerts a decisive influence on residual stress1 formation. Rapid cooling causes the crucible exterior to contract faster than its interior, transmitting thermal gradients back into zirconia components.

Empirical observations show that cooling rates above 8 °C/min between 1,000 °C and 600 °C increase the incidence of micro-warping by more than 25%. Accordingly, staged cooling profiles with reduced rates of 3–5 °C/min are commonly adopted.

Such controlled cooling allows gradual stress relaxation, preserving dimensional accuracy and minimizing post-sintering distortion.

Temperature Profile Summary

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Heating rate (°C/min) | 3–7 | Synchronizes crucible and load temperature |

| Temperature lag above 900 °C (°C) | <10 | Improves uniform densification |

| High-temperature dwell (min) | 90–120 | Reduces internal gradients |

| Cooling rate 1000–600 °C (°C/min) | 3–5 | Limits residual stress |

| Warp incidence reduction (%) | >20 | Improves dimensional stability |

In brief, temperature profiles must be tuned to the combined thermal behavior of furnace, crucible, and zirconia load.

When temperature control aligns with zirconia sintering crucible use, densification becomes predictable rather than reactive.

Beyond thermal input alone, gas exchange and internal airflow within the crucible exert a measurable influence on sintering uniformity.

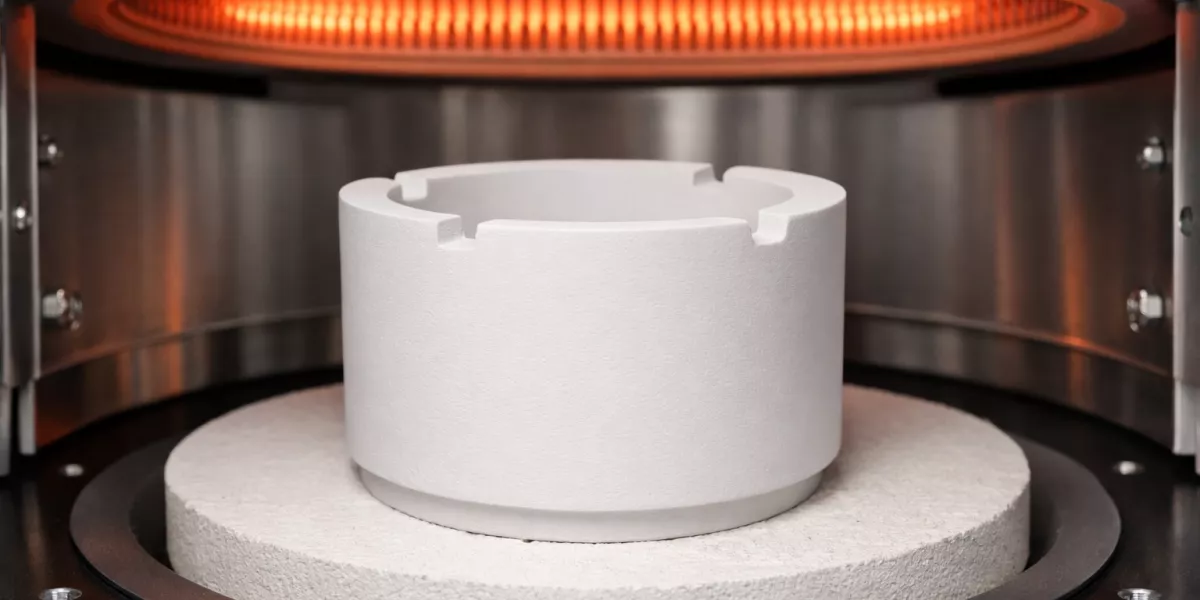

Atmosphere and Airflow Behavior Inside the Crucible

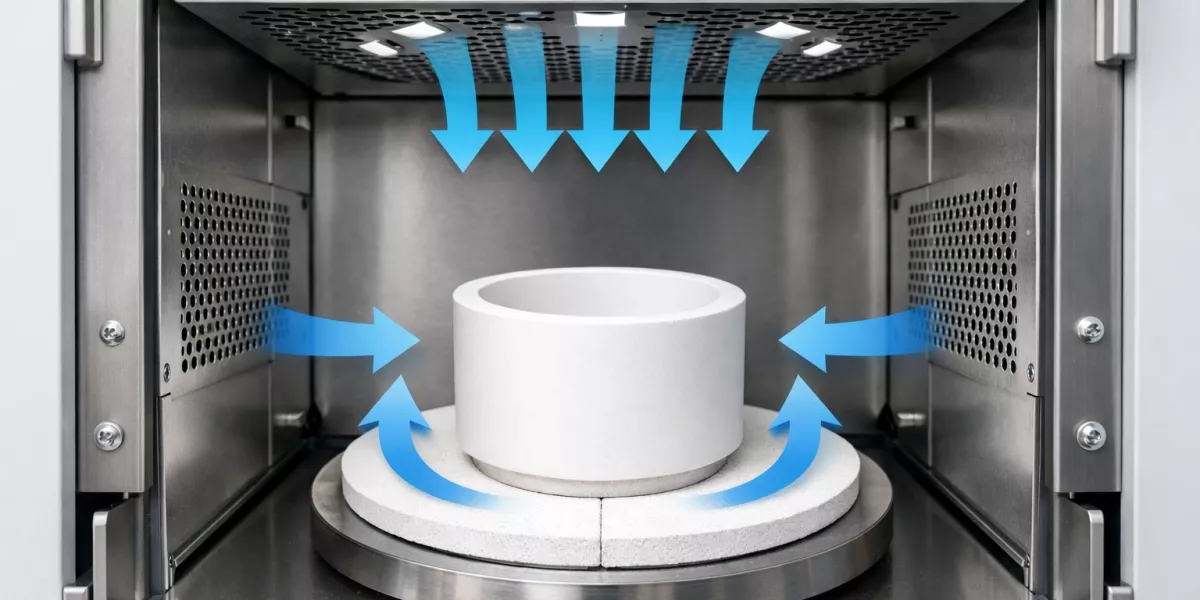

Atmosphere behavior within zirconia sintering crucible use is frequently assumed to mirror the furnace chamber. However, the crucible geometry—particularly its open top, thick walls, and rim notches—creates a semi-enclosed micro-environment. Consequently, airflow patterns and oxygen exchange inside the crucible can differ measurably from bulk furnace conditions.

Natural Convection Through Rim Notches

Rim notches act as controlled convection channels rather than incidental cutouts. During heating, temperature differentials between the crucible interior and surrounding chamber generate buoyancy-driven gas flow through these openings.

Thermal visualization studies indicate that properly distributed rim notches promote circulation velocities of approximately 0.02–0.05 m/s inside the crucible at temperatures above 1,000 °C. As a result, stagnant thermal pockets are reduced, and internal temperature gradients decline.

Conversely, partial obstruction of notches—such as asymmetric loading—can suppress convection by more than 40%, leading to localized overheating near the crucible wall.

Oxygen Exchange and Heat Distribution

Oxygen exchange inside a zirconia sintering crucible influences both heat transfer and surface chemistry. Although zirconia itself remains stable, surrounding supports and binders respond sensitively to oxygen availability.

Measured oxygen partial pressure2 inside a loaded crucible can deviate by 5–10% from chamber averages during rapid heating. Consequently, heat distribution becomes uneven as radiative and convective contributions shift.

Maintaining unobstructed airflow paths ensures that oxygen exchange remains gradual and spatially uniform, thereby stabilizing thermal exposure across all zirconia components.

Interaction With Furnace Venting Design

Furnace venting architecture governs how effectively gases entering and exiting the crucible are replenished. Top-vented systems typically reinforce upward convection, whereas side-vented designs produce lateral flow components.

Comparative trials show that mismatches between crucible orientation and furnace venting can increase internal temperature dispersion by up to 15 °C. Therefore, aligning crucible placement with dominant venting directions improves airflow predictability.

In such cases, atmosphere behavior inside the crucible becomes an extension of furnace design rather than an isolated variable.

Atmosphere and Airflow Summary

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Internal convection velocity (m/s) | 0.02–0.05 | Reduces stagnant zones |

| Oxygen deviation vs chamber (%) | <5 | Stabilizes surface reactions |

| Temperature dispersion (°C) | <8 | Improves uniform heating |

| Notch obstruction (%) | <20 | Maintains airflow efficiency |

| Venting alignment benefit (°C) | −10 to −15 | Lowers gradient magnitude |

Overall, airflow and atmosphere inside the crucible define a micro-thermal system that must be respected during process design.

When airflow behavior is understood and preserved, zirconia sintering crucible use supports consistent thermal exposure rather than introducing hidden variability.

As sintering cycles accumulate, the crucible’s response to heat and load evolves in ways that subtly alter process behavior.

Repeated Use Effects on Process Parameters

Repeated zirconia sintering crucible use introduces progressive changes that are subtle yet consequential. Moreover, these changes do not indicate material failure but reflect thermal aging and surface evolution inherent to high-temperature ceramics. Consequently, process parameters that remain static across long service periods often lose alignment with actual crucible behavior.

Thermal Aging of Zirconia Crucibles

Thermal aging manifests primarily as gradual redistribution of internal stresses and minor changes in effective thermal conductivity. After 30–50 sintering cycles above 1,400 °C, zirconia crucibles commonly exhibit conductivity variations of 5–8%, particularly near the flat base where heat flux is highest.

In monitored operations, this shift produces a measurable delay in internal temperature rise, extending time-to-equilibrium by 6–10 minutes during ramp phases. As a result, zirconia parts may experience prolonged exposure to intermediate temperatures where grain coarsening3 accelerates.

Therefore, recognizing thermal aging as a predictable phenomenon allows proactive parameter adjustment rather than reactive correction.

When Process Parameters Require Adjustment

Parameter revision should be triggered by behavioral indicators, not arbitrary cycle counts. Key signals include widening shrinkage dispersion, delayed densification onset, or increasing temperature offsets between thermocouple readings and part response.

Statistical tracking shows that once dimensional variance exceeds ±0.18% across identical loads, minor adjustments—such as extending dwell time by 10–15% or reducing heating rate by 1–2 °C/min—restore stability. Consequently, modest tuning often suffices without replacing the crucible.

In practice, parameter adaptation aligned with crucible aging extends usable service life by 25–40%, improving overall process efficiency.

Repeated Use Summary

| Parameter | Typical Range | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Service cycles before adjustment (count) | 30–50 | Onset of thermal aging |

| Thermal conductivity change (%) | 5–8 | Alters heat transfer rate |

| Time-to-equilibrium increase (min) | 6–10 | Delays densification |

| Shrinkage variance trigger (%) | ±0.18 | Signals parameter drift |

| Service life extension (%) | 25–40 | Achieved via tuning |

In essence, repeated-use effects redefine process baselines rather than compromise crucible integrity.

When parameter management evolves alongside zirconia sintering crucible use, long-term stability becomes achievable without unnecessary component replacement.

Between successive firings, handling and cleaning practices directly affect how consistently the crucible performs over time.

Cleaning and Handling Between Sintering Cycles

Between sintering cycles, zirconia sintering crucible use requires disciplined handling rather than aggressive intervention. Typically, the crucible surface remains chemically inert; however, residual particles and contact marks may accumulate and influence subsequent heat transfer. Consequently, cleaning practices should preserve surface integrity while removing only functionally relevant residues.

-

Dry particulate removal

Loose zirconia dust or setter debris should be removed using soft ceramic brushes or low-pressure compressed air below 0.2 MPa. Excessive force increases surface abrasion, which may elevate friction during shrinkage in later cycles. -

Restricted wet cleaning

Wet cleaning is generally unnecessary and may introduce moisture retention. If required, deionized water with conductivity below 5 µS/cm should be used, followed by drying at 120–150 °C for at least 60 minutes to prevent vapor-induced thermal lag. -

Handling and storage discipline

Crucibles should be stored on flat ceramic shelves rather than metallic racks. Repeated contact with metal surfaces has been shown to increase base surface roughness by 10–15% over extended use, subtly altering contact mechanics.

Subsequently, consistent handling between cycles ensures that observed process variations reflect thermal behavior rather than incidental surface changes.

Cleaning and Handling Summary

| Parameter | Recommended Practice | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Air cleaning pressure (MPa) | ≤0.2 | Limits surface abrasion |

| Water conductivity (µS/cm) | <5 | Avoids ionic residue |

| Drying temperature (°C) | 120–150 | Removes absorbed moisture |

| Drying duration (min) | ≥60 | Stabilizes thermal response |

| Surface roughness increase (%) | <10 | Preserves contact behavior |

In short, conservative cleaning preserves crucible function more effectively than intensive treatment.

When cleaning aligns with zirconia sintering crucible use principles, process repeatability is maintained without introducing secondary variability.

Deviations from established use principles often manifest as repeatable process errors rather than isolated failures.

Common Process Errors When Using Zirconia Sintering Crucibles

In routine operation, zirconia sintering crucible use often deviates from intended design logic through small but compounding errors. Typically, these errors emerge after stable early results, when parameter discipline relaxes and loading practices drift. Consequently, identifying recurring misjudgments helps prevent cumulative variability that cannot be corrected by furnace recalibration alone.

-

Overloading the crucible interior

Excessive part density reduces internal airflow and increases thermal shielding. Measurements show that load coverage beyond 70% of internal area raises internal temperature dispersion by 10–18 °C, thereby destabilizing densification timing. -

Ignoring rim notch functionality

Treating rim notches as incidental geometry leads to asymmetric airflow blockage. In observed cases, partial obstruction increased localized overheating frequency by 25–30%, particularly near the crucible wall. -

Reusing unchanged temperature programs indefinitely

Static programs fail to account for crucible thermal aging. After 40+ cycles, unchanged profiles often correlate with shrinkage drift exceeding ±0.2%, even when furnace sensors remain nominal. -

Direct placement on abrasive or metallic surfaces

Repeated base contact with hard or metallic benches increases surface roughness, elevating friction during shrinkage. Roughness increases of 12–15% have been associated with higher warpage incidence.

Subsequently, these errors interact rather than act independently, amplifying their impact across multiple cycles.

Common Error Summary

| Error Category | Quantified Threshold | Typical Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Load coverage (%) | >70 | Increased thermal shielding |

| Rim notch obstruction (%) | >30 | Localized overheating |

| Static program cycles (count) | >40 | Shrinkage drift |

| Base roughness increase (%) | >12 | Elevated warpage risk |

| Temperature dispersion (°C) | >15 | Densification imbalance |

Overall, most process errors stem from misaligned assumptions rather than crucible limitations.

When these misjudgments are systematically corrected, zirconia sintering crucible use regains its intended role as a stabilizing element within the sintering system.

Even under ideal conditions, crucible geometry and material properties impose clear limits on how far process parameters can be pushed.

Process Optimization Boundaries Defined by the Crucible

Every zirconia sintering crucible introduces physical boundaries that define how far process parameters can be optimized. Moreover, these boundaries originate from geometry, thermal mass, and airflow characteristics rather than furnace control resolution. Consequently, understanding where optimization ends prevents excessive tuning that yields diminishing returns.

-

Thermal mass limitation

Thick crucible walls impose a lower limit on effective heating rates. When ramp speeds exceed 8–10 °C/min, internal temperature lag increases disproportionately, often surpassing 30 °C above 900 °C, regardless of furnace capability. -

Airflow saturation threshold

Rim notch design supports natural convection only up to a defined load density. Once internal coverage exceeds 75%, airflow benefits diminish sharply, and further spacing adjustments fail to restore uniformity. -

Mechanical freedom constraint

Flat-base contact geometry restricts complete elimination of frictional interaction. Even with optimized supports, contact-induced resistance cannot be reduced below approximately 3–5% of total shrinkage force. -

Cooling rate floor

Below 2–3 °C/min, further cooling deceleration does not significantly reduce residual stress but substantially increases cycle duration. Therefore, excessively slow cooling offers limited practical advantage.

Subsequently, recognizing these boundaries enables rational decision-making, balancing achievable stability against operational efficiency.

Optimization Boundary Summary

| Boundary Aspect | Practical Limit | Observed Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum heating rate (°C/min) | 8–10 | Prevents excessive temperature lag |

| Load coverage ceiling (%) | ~75 | Preserves airflow effectiveness |

| Minimum friction contribution (%) | 3–5 | Defines shrinkage freedom limit |

| Effective cooling floor (°C/min) | 2–3 | Balances stress relief and time |

| Temperature lag above 900 °C (°C) | <30 | Maintains process predictability |

Ultimately, process optimization succeeds only when guided by physical constraints rather than theoretical control limits.

By respecting these boundaries, zirconia sintering crucible use supports stable, repeatable outcomes without unnecessary parameter escalation.

When operational variables remain controlled within those boundaries, output quality transitions from variability toward predictability.

From Stable Operation to Predictable Output

Once zirconia sintering crucible use is aligned with preparation discipline, loading geometry, thermal profiles, airflow behavior, and optimization limits, process stability evolves into predictable output. At this stage, variability no longer originates from the crucible–furnace system but reflects upstream material consistency and downstream inspection criteria.

-

Process repeatability consolidation

When critical parameters remain within validated ranges, cycle-to-cycle dimensional deviation typically stabilizes below ±0.12–0.15% across identical zirconia batches. Consequently, statistical drift diminishes, and corrective adjustments become infrequent. -

Thermal behavior normalization

After stabilization, internal temperature offsets relative to furnace setpoints generally remain within ±5–8 °C throughout the sintering window. As a result, densification timing becomes consistent, supporting uniform grain development and mechanical performance. -

Output predictability window

Under controlled conditions, predictable performance is sustained for 30–60 consecutive cycles before minor parameter refinement is required. This window enables production planning without continuous recalibration.

Subsequently, the crucible transitions from a variable component into a known system constant, allowing process control to focus on material input and dimensional verification rather than furnace-side intervention.

Stability to Output Summary

| Performance Indicator | Typical Range | Practical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensional deviation (%) | ±0.12–0.15 | Consistent part geometry |

| Internal temperature offset (°C) | ±5–8 | Uniform densification |

| Stable cycle window (count) | 30–60 | Reduced recalibration |

| Parameter adjustment frequency | Low | Predictable scheduling |

| Scrap rate trend | Declining | Improved yield stability |

In conclusion, predictable output is achieved when zirconia sintering crucible use is treated as an integrated process element rather than an isolated accessory.

When stability is sustained, technical confidence replaces trial-based adjustment, enabling controlled scaling and consistent production performance.

Taken together, these operational factors form a coherent framework for understanding how zirconia sintering crucibles shape process outcomes.

Consolidated Operational Perspective on Zirconia Sintering Crucible Use

At this stage, zirconia sintering crucible use can be evaluated not as a collection of isolated practices, but as a closed-loop operational system. Preparation discipline, geometric loading logic, thermal coordination, airflow awareness, and optimization boundaries now operate cohesively rather than independently. Consequently, process behavior becomes explainable, reproducible, and auditable.

More importantly, this consolidation clarifies responsibility boundaries. Variability that persists within validated crucible parameters typically originates from material batch differences, green body preparation, or measurement methodology, rather than furnace-side execution. As a result, troubleshooting efforts shift upstream instead of repeatedly targeting temperature programs or hardware settings.

In mature operations, this perspective reduces reactive intervention and supports structured process ownership. When zirconia sintering crucible use is fully internalized as a system constraint, technical teams gain the confidence to scale output, refine tolerances, and document performance windows without reliance on iterative trial cycles.

Operational Consolidation Summary

| Dimension | Controlled State | Resulting Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Crucible preparation | Standardized | Eliminates early-cycle drift |

| Loading geometry | Repeatable | Stabilizes shrinkage symmetry |

| Thermal profiles | Adapted | Predictable densification |

| Airflow behavior | Preserved | Uniform heat exposure |

| Optimization limits | Respected | Avoids over-tuning |

| Process ownership | Defined | Sustainable consistency |

Conclusion

In the final analysis, zirconia sintering crucible use defines the physical envelope within which reliable sintering occurs.

When this envelope is respected, process control evolves from adjustment to assurance.

For operations seeking higher repeatability or tighter dimensional control, reviewing crucible use practices often reveals optimization potential without equipment changes.

Technical clarification or application-specific discussion can further refine crucible integration into existing sintering workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can zirconia sintering crucible use alone correct part deformation issues?

Crucible use stabilizes thermal and mechanical conditions, but deformation linked to green body defects or material inconsistencies requires upstream correction.

How often should process parameters be formally reviewed?

Formal review is typically effective after each stable cycle window of 30–60 runs or when dimensional variance trends exceed defined thresholds.

Is crucible replacement always required when variability increases?

No, variability frequently responds to parameter refinement aligned with crucible aging rather than immediate replacement.

Does consistent crucible use reduce reliance on furnace recalibration?

Yes, disciplined crucible integration often stabilizes internal conditions, reducing the frequency of furnace-side adjustments.

References:

-

Residual stress refers to internal stresses retained in ceramics after high-temperature processing and cooling. ↩

-

Oxygen partial pressure defines the concentration of oxygen in a gas environment, affecting thermal and chemical behavior. ↩

-

Grain coarsening describes the growth of crystalline grains at elevated temperatures, influencing mechanical properties. ↩