alumina furnace tube geometry shapes heat transfer, temperature uniformity, and energy use from the first ramp. Small changes in diameter, wall thickness, aspect ratio, and cross-section alter convection, radiation, and axial conduction in measurable ways.

Choosing an alumina furnace tube with the right diameter, wall, length, and profile sets the convective coefficient, radiation view factors, and end-effect penetration length. Round, moderate-wall alumina furnace tube designs with controlled flow and adequate heated-zone margin routinely achieve ±3–5 °C uniformity; larger or cornered sections need forced flow or multi-zone compensation.

The following sections convert alumina furnace tube geometry into governing numbers and practical specifications for repeatable outcomes and lower energy cost.

How Do Tube Diameter and Gas Boundary Layer Effects Influence Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient in Alumina Furnace Tubes?

Short cycle times suffer when an alumina furnace tube diameter thickens thermal boundary layers and suppresses h.

For natural convection at 1400–1600 °C in an alumina furnace tube, h typically falls from ~95–110 to ~45–60 W/m²·K as diameter grows from 40 mm to 100+ mm. Forced flow at 1–3 m/s in an alumina furnace tube lifts h to ~150–250 W/m²·K.

In an alumina furnace tube, diameter sets Rayleigh and Reynolds numbers1, which define regime and mixing. With Nu≈C·Raⁿ, a 60 mm alumina furnace tube at 1500 °C and ΔT=50 °C sits near laminar limits; 100 mm moves toward turbulent natural convection, evening circumferential temperatures but adding ±5–15 °C temporal swings. Because the alumina furnace tube also affects thermal mass, time to equilibrium scales roughly with D·(1/h). Forced flow in the alumina furnace tube restores high h and trims the time constant by 2–4×.

Convective heat transfer coefficients by diameter and regime in an alumina furnace tube

| Diameter (mm) | Regime | Velocity (m/s) | h (W/m²·K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Natural | 0 | 95–110 |

| 60 | Natural | 0 | 70–85 |

| 80 | Natural | 0 | 55–70 |

| 100–120 | Natural | 0 | 45–60 |

| 60–120 | Forced turbulent | 1–3 | 150–250 |

Boundary layer thickness scaling with tube diameter

Boundary layers in the alumina furnace tube thicken with axial distance, scaling as δ∝√(x·ν/u) for forced flow or δ∝√(x·α) for natural convection. Larger bores increase characteristic lengths and promote thicker thermal layers, raising resistance and lowering h. This is why a smaller alumina furnace tube often heats faster at the same flow.

Summary of entrance-length impacts for an alumina furnace tube

| Condition | Scaling driver | Effect on δ | Practical implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forced convection | Re↑ with u,D | δ thinner | Higher Nu, faster ramps |

| Natural convection | Ra↑ with D³ | δ thicker | Lower h without forcing |

| Higher gas conductivity | Increases Nu | Mixed | Helps h but thickens δ |

Rayleigh number transition and regime management

As Ra=gβΔTD³/(να) rises with D³ in an alumina furnace tube, larger bores cross the ~10⁷ threshold, entering turbulent natural convection. Turbulence improves mixing but adds oscillations that complicate tight PID control. Keeping ΔT moderate within the alumina furnace tube helps maintain steady profiles for precision work.

Transition window guidance within an alumina furnace tube

| D (mm) | ΔT (°C) | Approx. Ra | Regime tendency | Control advice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 50 | ~8×10⁶ | Laminar | Favor stability |

| 100 | 50 | ~3.7×10⁷ | Turbulent | Expect fluctuations |

| 80 | 80 | ~3×10⁷ | Transitional | Add flow to stabilize |

Forced convection enhancement and velocity targeting

Turbulent2 forced flow in the alumina furnace tube reduces δ by ~3–5× and linearizes axial temperature. Use Re=uD/ν and target Re>5,000 with 1–3 m/s bulk velocity. Flow straighteners and gentle diffusers prevent recirculation near supports.

Velocity and Re targets for an alumina furnace tube

| D (mm) | Target u (m/s) | Target Re (–) | Expected h (W/m²·K) | Uniformity (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 1.5 | >6,000 | 170–210 | ±2–3 |

| 80 | 2.0 | >7,000 | 170–230 | ±3–5 |

| 100 | 2.5–3.0 | >8,000 | 180–250 | ±4–6 |

What Wall Thickness Optimization Principles Balance Radial Thermal Resistance Against Axial Temperature Gradient Requirements in Alumina Furnace Tubes?

Thin walls speed heat-in, but thick walls spread heat along the axis inside an alumina furnace tube.

Radial drops scale with thickness because k≈28–32 W/m·K; thicker walls in an alumina furnace tube raise ΔT_radial yet reduce end-effect axial gradients via stronger conduction.

For a 50 mm OD alumina furnace tube with 5 mm wall at 1500 °C and h≈80 W/m²·K, radial resistance near 0.001 K/W·m causes a 10–15 °C bore deficit at 10 kW/m heat flux. Raising wall from 4 mm to 10–12 mm increases ΔT_radial from ~6–10 °C to ~20–30 °C but shrinks edge-to-center axial drop by ~40–50%. The alumina furnace tube time constant τ∝(ρc_p t)/h, so doubling t roughly doubles heat-up time. A weighted objective Φ selects t/D≈0.08–0.12 for radial precision, 0.15–0.20 for long uniform zones, and 0.12–0.15 for fast cycling.

Wall thickness effects within an alumina furnace tube

| t/D (–) | ΔT_radial at 1500 °C (°C) | Axial drop over 200 mm (°C) | Relative heating time (–) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.08–0.12 | 6–12 | 35–50 | 1.0 |

| 0.15–0.20 | 12–30 | 20–30 | 1.7–2.0 |

| 0.12–0.15 | 10–20 | 25–40 | 1.3–1.6 |

Radial thermal resistance prediction

Radial profiles inside an alumina furnace tube follow T(r)=T_bore+(T_outer−T_bore)·ln(r/r_i)/ln(r_o/r_i). With constant OD, thicker walls depress bore temperature more for the same external heat input, especially when h is low. Transitioning the alumina furnace tube to forced flow offsets this penalty.

Parameter sensitivities for an alumina furnace tube

| Variable | Increase | Radial effect | Axial effect | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall thickness | + | ΔT↑ | Edge drop↓ | Time↑ |

| h (forced) | + | ΔT↓ | Edge drop↓ | Time↓ |

| OD at fixed t/D | + | ΔT~ | End effects↑ | Time↑ |

Axial conduction and end-effect mitigation

Axial conduction3 q=−k_eff A_cross dT/dx rises with wall area in an alumina furnace tube, reducing the edge deficit. Thicker walls carry more heat from the hot center to the ends, shrinking gradient length and flattening the working region. Benefits are strongest in single-zone furnaces.

Axial smoothing performance for an alumina furnace tube

| Wall (mm) | Edge deficit over 200 mm (°C) | Recommended control |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 35–50 | Multi-zone or guard heaters |

| 8–10 | 20–30 | Mild end compensation |

| 12 | 18–25 | Minimal compensation |

Multi-objective selection across goals

Select weights w₁,w₂,w₃ from process goals. Precision sintering in an alumina furnace tube prioritizes w₁; long hot zones prioritize w₂; throughput prioritizes w₃. Verify with a short CFD run and a 10–20-point thermocouple map.

How Do High Aspect Ratio Designs Create End-Effect Temperature Non-Uniformity and What Quantitative Models Predict Gradient Magnitude in Alumina Furnace Tubes?

Long alumina furnace tube designs lose heat at the ends, pulling gradients into the working zone.

Temperature decays exponentially from the heated-zone boundary with λ=√(kA/(hP)); ensuring L_heated≥L_working+4λ+2λ·ln(ΔT/ΔT_allow) preserves ±5 °C uniformity in the alumina furnace tube.

End effects combine axial conduction, radiation to ambient, and natural convection around exposed sections of the alumina furnace tube. With λ≈180–250 mm, placing the working zone at least 2λ inside the heated region suppresses intrusion. Multi-zone control with +20–40 °C end compensation flattens profiles to ±3–5 °C over 600–800 mm; guard heaters can halve λ and shorten required heated length.

Heated-zone planning for an alumina furnace tube

| Working zone (mm) | End deficit (°C) | Allowed variation (°C) | Minimum L_heated (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | 50 | 5 | ≈1720 |

| 600 | 50 | 5 | ≈2120 |

| 600 | 30 | 5 | ≈1900 |

End-effect heat loss and axial mechanics

Radiation scales with εσA(T⁴−T_a⁴) and dominates at 1200–1600 °C for the alumina furnace tube ends; convection adds 5–15 W/m²·K depending on airflow. Axial conduction tries to refill the ends; thicker walls assist but rarely cancel radiation losses without control measures.

Control options ranked for an alumina furnace tube

| Option | Uniformity gain | Cost/complexity | When to use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-zone setpoint lift | High | Medium | Long L/D |

| Guard heaters | Medium–High | Medium | Space-limited |

| Thicker wall | Medium | Low | Single-zone only |

Exponential decay characterization

Solving d²T/dx²−(hP)/(kA)(T−Ta)=0 yields T(x)=T∞+(Tf−T∞)e^(−x/λ). A quick mapping run inside the alumina furnace tube estimates λ, enabling swift layout of heated-zone margins and validation of control recipes.

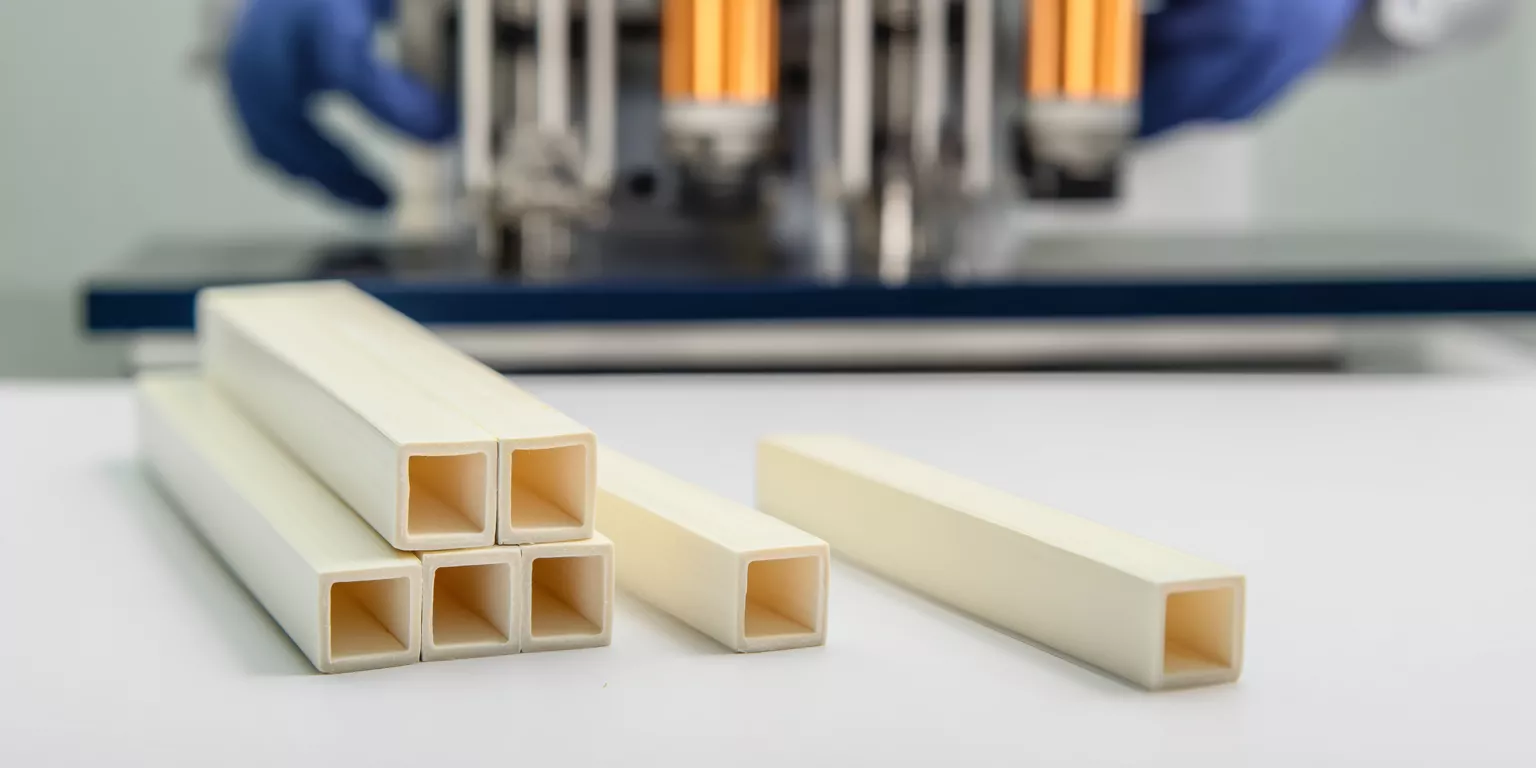

What Radiation Heat Transfer Efficiency Differences Distinguish Square and Oval Cross-Sections from Round Alumina Tubes in Alumina Furnace Tubes?

Flat faces see higher view factors; corners overheat around an alumina furnace tube cross-section.

Square sections raise wall-to-tube view factors to ~0.65–0.75 and heat faster but show ±20–30 °C perimeter variation; round sections sit ~0.40–0.55 with ±5–8 °C variation inside the alumina furnace tube.

Deeper analysis. Square faces align normal to furnace walls, increasing exchange. Corners receive multi-wall radiation, creating 1.4–1.6× local heat-flux hot spots. Ovals add 8–12% radiation versus rounds but keep smoother circumferential profiles than squares. Perimeter grows by ~1.27× for squares at equal hydraulic diameter, raising both heat-in and heat-out in the alumina furnace tube.

Cross-section impacts at 1500 °C for an alumina furnace tube

| Cross-section | Relative view factor (–) | Perimeter vs round (–) | Circumferential variation (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Round | 0.40–0.55 | 1.00 | ±5–8 |

| Oval | 0.45–0.60 | 1.10–1.15 | ±8–12 |

| Square | 0.65–0.75 | 1.27 | ±20–30 |

Radiation exchange geometry

With ε_eff=1/(1/ε_tube + A_tube/A_wall·(1/ε_wall−1)), low ε_tube≈0.30–0.40 limits absolute flux. Geometry then dominates via F_wall→tube. Aligning ovals with the major axis facing walls maximizes exchange without square-corner hot spots inside the alumina furnace tube.

Orientation practices in an alumina furnace tube

| Orientation | View factor effect | Uniformity effect | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oval, major toward wall | ↑ | Mild variation | Preferred |

| Square, fixed | ↑↑ | Corner hot spots | Avoid for precision |

| Square, rotated per cycle | ↑ | Averaged but mixed | Conditional |

Surface area and efficiency trade-offs

Larger perimeter accelerates ramp but raises steady power draw. If energy cost or thermal symmetry is critical, rounds win; if takt time dominates, squares or ovals can be justified with control compensation in the alumina furnace tube.

How Does Fluid-Solid Coupled Simulation Reveal Geometric Parameter Control of Furnace Flow Field and Temperature Distribution for Alumina Furnace Tubes?

CFD shortens trials by turning alumina furnace tube geometry into fields and numbers.

Validated DO-radiation plus k-ε turbulence predicts ±5–8 °C outcomes after geometry tweaks that would take weeks by test-only loops in an alumina furnace tube project.

Deeper analysis. Build a mesh with 2–5 mm near walls; select laminar or k-ε by Re; set emissivities (ε_tube≈0.35, ε_wall≈0.80) and converge energy residuals <1e-5. Parametrics over D=40–120 mm, t=4–12 mm, L=0.5–2.0 m, and shapes show the dominant sensitivities for the alumina furnace tube. Velocity vectors reveal two counter-rotating cells in small D, shifting to asymmetric unsteady rolls in large D with ±8–15 °C fluctuations at 0.1–1 Hz. A mean absolute error of 8–15 °C at 1500 °C is sufficient for screening and selection.

Geometry sensitivities from coupled simulation for an alumina furnace tube

| Parameter | Change | Uniformity impact (°C) | Energy impact (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | +40→+120 mm | ±5→±20 | +10–15 |

| Wall thickness | 5→10 mm | −15 to −25 axial | +30–70 time |

| Cross-section | Round→Square | ±8→±30 | +15–25 |

| Forced flow | 0→2 m/s | −10 to −20 | −10–20 |

Coupled equation formulation and wall treatment

Continuity, momentum, and energy link through buoyancy and radiative sources in the alumina furnace tube model. Proper near-wall treatment (targeted y⁺) is essential to capture δ and wall heat flux that set h and λ.

Simulation setup checklist for an alumina furnace tube

| Item | Target | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Near-wall size | 2–5 mm | Resolve δ |

| Residuals | <1e-5 | Thermal closure |

| Probes | 10–20 pts | Compare to test |

| Scheme | 2nd-order energy | Reduce dissipation |

Parametric studies and decision points

Map h, ΔT_radial, ΔT_axial, and circumferential spread versus D, t, and flow within the alumina furnace tube. Identify knees where small geometry changes yield outsized uniformity gains, then lock specs before hardware.

Conclusion

Geometry sets the regime in the alumina furnace tube; targeted flow and zoning recover uniformity at the lowest energy cost.

FAQ

How does an alumina furnace tube diameter change heat-up time at high temperature?

Heat-up time scales with D·(1/h) inside an alumina furnace tube. Larger diameters thicken boundary layers and reduce h under natural convection. Forced flow restores h and cuts time constants by 2–4×.

What commercial risks matter when choosing square vs round for an alumina furnace tube?

Square sections increase power use by ~15–25% and raise perimeter non-uniformity. Round alumina furnace tube profiles reduce energy and improve yield. Model operating cost per batch before selection.

What information should purchasing provide for a custom alumina furnace tube?

Share target uniformity (± °C), working length, furnace setpoint, permitted flow rate, and cross-section preference. Include constraints on heater zones and chamber size to right-size t/D and λ margins for the alumina furnace tube.

How does an alumina furnace tube compare with quartz tubes for uniformity?

Alumina’s higher emissivity and opacity shift heating toward surface radiation and wall conduction in the alumina furnace tube, often improving near-wall stability. Quartz transmits radiation, which can complicate internal gradients without baffles.

References:

-

This resource will provide insights into the importance of Reynolds numbers in determining flow regimes and mixing efficiency. ↩

-

Learn how turbulent flow enhances heat transfer and efficiency in furnace tubes, crucial for optimizing industrial processes. ↩

-

Understanding axial conduction is crucial for optimizing heat transfer in furnace designs. ↩