Alumina Plate failures can halt heating systems abruptly; consequently, OEM schedules and process qualification often collapse when plates warp, crack, or contaminate hot zones.

This article consolidates Alumina Plate selection and design logic for industrial furnaces, heat-treatment equipment, high-temperature reaction systems, and lab-to-pilot heating platforms, with emphasis on thermal profiles, atmosphere compatibility, mechanical load paths, and lifecycle reliability.

Accordingly, the discussion moves from thermal operating envelopes to material architecture, thermo-mechanical stress interactions, geometry decisions, and application-driven selection, enabling engineers to specify Alumina Plate with fewer iterations and higher first-pass yield.

Before specifying purity, thickness, or machining, furnace engineers must establish an operating envelope, because temperature-time exposure and atmosphere boundaries govern every Alumina Plate risk mode.

Thermal Operating Envelopes in Industrial Heating Systems

Industrial heating systems impose thermal stress through both absolute temperature and how temperature changes over time. Furthermore, the most damaging events often occur during ramp transitions, door openings, and unplanned cool-downs rather than during steady dwell. Consequently, OEM teams benefit when Alumina Plate is specified against real profiles instead of nominal furnace ratings.

In practice, a furnace labeled 1600 °C rarely exposes every internal component to 1600 °C continuously. Instead, Alumina Plate sees spatial gradients, intermittent peak zones near heaters, and atmosphere-driven surface reactions that shift with process recipes. Therefore, the operating envelope must combine temperature, time-at-temperature, ramp rates, and atmosphere composition to remain engineering-meaningful.

Continuous Versus Intermittent Temperature Exposure

Continuous exposure typically means a stable hot zone where Alumina Plate remains above 1200–1550 °C for 8–72 hours per cycle, often in sintering or diffusion schedules. Intermittent exposure, by contrast, occurs in thermal cycling, belt furnaces, and pilot reactors where plates experience repeated dwell segments of 15–90 minutes with frequent ramps.

From field commissioning, engineers often find that intermittent programs generate more cracking even when peak temperature is lower, because repeated strain accumulation acts like thermal fatigue. For example, 300–800 cycles with ΔT of 250–400 °C can produce edge microcracks that later propagate under fixture loads. Consequently, plate life is frequently governed by cycle count and ramp history rather than by peak setpoint alone.

Therefore, continuous profiles prioritize creep resistance and dimensional stability, while intermittent profiles prioritize thermal shock tolerance and crack arrest behavior. Alumina Plate selection should be keyed to exposure style first, since it dictates which failure mode dominates the lifecycle.

Atmosphere Effects on Alumina Plate Stability

Atmosphere chemistry1 alters surface stability, interfacial reactions, and contamination behavior. In oxidizing air, Alumina Plate is generally stable; however, trace alkali vapors and silica-bearing dust can form low-melting boundary films that accelerate warpage above 1350–1450 °C. In inert atmospheres such as nitrogen or argon, chemical stability remains high, yet contamination from furnace insulation binders may accumulate on the plate surface.

Reducing atmospheres introduce additional constraints. For instance, carbon-bearing environments can promote interfacial reactions with adjacent refractories, while certain metal vapors can deposit conductive films that complicate electrical isolation in heated fixtures. In pilot systems, engineers often observe that plate discoloration correlates with atmosphere carryover rather than with alumina degradation; nonetheless, deposited films can change emissivity and local heat flux by 10–20%, shifting hot-spot locations.

Therefore, the operating envelope must record atmosphere type, impurity sources, and expected vapor species. Alumina Plate durability depends as much on atmosphere cleanliness as on ceramic purity, particularly in mixed-use furnaces running multiple recipes.

Temperature Gradients and Localized Hot Zones

Even well-tuned furnaces exhibit gradients. Hot zones near heating elements can exceed average setpoint by 30–80 °C, while shadowed regions behind fixtures may run cooler by 20–60 °C. These gradients matter because Alumina Plate is brittle and responds to differential expansion through bending and edge tension.

A common OEM oversight is designing plates as if they are uniformly heated. In reality, heater proximity, radiant view factor, and load placement create asymmetric heating that induces curvature. For example, a 300 mm plate experiencing a through-thickness gradient of only 25–40 °C can develop measurable bowing if one face sees higher radiative flux. During validation runs, engineers often detect this first as uneven contact pressure and then as crack initiation at constrained corners.

Therefore, gradient mapping should be treated as a specification input. If gradients exceed 50 °C locally, edge geometry, thickness, and support pattern become primary design levers, not secondary refinements.

Summary of Operating Envelope Parameters

| Operating envelope variable | Typical industrial band | Primary risk on Alumina Plate | Engineering control lever |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak temperature (°C) | 1200–1650 | Creep and warpage | Purity and density |

| Dwell duration (h) | 0.25–72 | Grain-boundary softening | Grade selection |

| Ramp rate (°C/min) | 2–20 | Thermal shock cracking | Thickness and edges |

| Cycle count (cycles) | 50–1000 | Fatigue crack growth | Support pattern |

| Local hot-spot offset (°C) | 30–80 | Asymmetric bending | Heater distance |

| Atmosphere impurity level | low to moderate | Surface films and reactions | Furnace housekeeping |

Before thermal loads translate into mechanical stress, the internal structure of Alumina Plate must be examined, because microstructural architecture governs how heat is absorbed, redistributed, and tolerated at elevated temperatures.

Material Architecture of Alumina Plate for High Temperature Use

Material architecture determines whether Alumina Plate behaves as a stable structural element or as a latent failure trigger once temperatures exceed 1200 °C. Moreover, differences that appear minor at room temperature often become dominant under prolonged heating. Therefore, purity, grain structure, and density must be evaluated together rather than in isolation.

In high-temperature furnaces, Alumina Plate rarely fails by immediate fracture. Instead, gradual deformation, surface interaction, or microcrack accumulation emerges as the governing mechanism. Consequently, material architecture defines not only peak capability but also how performance evolves over hundreds of operating hours.

Alumina Purity and Secondary Phase Influence

Alumina purity establishes the baseline resistance to grain-boundary softening and viscous deformation. Plates with 96% Al₂O₃ typically contain glassy secondary phases that begin to soften above 1350–1400 °C, whereas 99.0–99.5% Al₂O₃ grades shift this threshold closer to 1500–1600 °C. In long dwell furnaces, this difference translates directly into dimensional retention.

During pilot sintering trials, engineers often observe that lower-purity plates remain intact visually but exhibit gradual bowing after 20–40 hours at temperature. This deformation complicates fixture alignment and alters heat flow, even without visible cracking. By contrast, high-purity Alumina Plate maintains shape integrity longer, reducing recalibration cycles and unplanned shutdowns.

Therefore, purity selection should follow thermal dwell expectations rather than peak temperature alone. Extended dwell above 1400 °C strongly favors ≥99% alumina, especially for load-bearing or alignment-critical plates.

Grain Structure and High Temperature Creep Resistance

Grain size and distribution govern creep resistance under sustained load. Fine-grained alumina typically exhibits higher room-temperature strength; however, at elevated temperatures, excessive grain boundary area accelerates diffusion-driven creep. Conversely, controlled grain growth improves creep resistance but may reduce thermal shock tolerance.

In furnace decks supporting fixtures or heating elements, creep deformation of only 0.1–0.3% strain can misalign components significantly over spans of 300–500 mm. Field data from continuous furnaces indicates that coarse, equiaxed grains reduce creep rate by up to 40% at 1450–1550 °C, compared with fine-grained counterparts under identical loading.

As a result, grain structure must be matched to load duration and magnitude. For static support roles, creep resistance outweighs room-temperature flexural strength, whereas shock-dominated zones benefit from moderated grain size.

Density and Porosity Control at Elevated Temperatures

Bulk density and residual porosity influence both mechanical integrity and thermal behavior. Plates with density below 3.6 g/cm³ often contain interconnected porosity that acts as stress concentrators during thermal cycling. At high temperature, these pores can coalesce, amplifying deformation under compressive load.

Engineers frequently encounter cases where two plates of identical purity perform differently due to density variance. In one commissioning example, plates at 98% theoretical density exhibited early sagging after 500 hours, while plates above 99.5% density maintained flatness within ±0.3 mm over the same interval. This difference directly impacted fixture alignment and process repeatability.

Therefore, density should be specified explicitly, not inferred from grade labels. High-temperature Alumina Plate benefits from density levels ≥99% of theoretical, particularly in structural applications.

Summary of Material Architecture Parameters

| Architecture parameter | Typical range | High-temperature impact | Selection priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alumina purity (%) | 96–99.5 | Softening onset | High |

| Grain size (μm) | 3–15 | Creep resistance | Medium to high |

| Bulk density (g/cm³) | 3.6–3.9 | Warpage control | High |

| Residual porosity (%) | <1–3 | Crack initiation | Medium |

| Secondary phase content | Low to moderate | Viscous flow | High |

| Long-dwell stability (h) | 20–500+ | Shape retention | Critical |

Before thermal stress is considered alone, mechanical load transmission within furnaces and reactors must be clarified, because Alumina Plate rarely operates without sustained or redistributed mechanical forces.

Mechanical Load Paths Inside Furnaces and Reactors

Mechanical load paths define how weight, constraint, and thermal expansion forces are transmitted through Alumina Plate during operation. Moreover, many failures attributed to “thermal issues” originate from overlooked mechanical interactions amplified by heat. Consequently, OEM designers must treat Alumina Plate as an active structural element rather than a passive liner.

In high-temperature systems, loads evolve with temperature. Fixtures soften, metals expand, and refractories creep, thereby altering how force is applied to ceramic plates. Therefore, understanding load paths across cold start, steady dwell, and cool-down stages is essential for reliable plate specification.

Static Loads from Fixtures and Heating Elements

Static loads2 typically arise from fixtures, heating elements, and supported workpieces. In industrial furnaces, Alumina Plate often supports distributed loads ranging from 0.05–0.3 MPa, depending on fixture mass and span. Although these stresses appear modest, elevated temperatures reduce elastic modulus by 20–35% above 1200 °C, increasing deflection sensitivity.

During commissioning of belt and batch furnaces, engineers frequently observe that plates remain intact yet exhibit measurable mid-span sag after 50–100 hours under constant load. For example, a 400 mm span plate carrying 12–18 kg can develop 0.5–1.2 mm deflection at 1450 °C, which subsequently redistributes contact pressure. As a result, local stress intensifies at supports, accelerating microcrack initiation.

Therefore, static load calculations must incorporate temperature-dependent modulus and creep, not room-temperature strength. Load per unit span is a more predictive metric than nominal fixture mass, especially for long dwell processes.

Differential Expansion Induced Stress

Differential thermal expansion generates secondary stresses when Alumina Plate interfaces with metals or refractories. Alumina exhibits a coefficient of thermal expansion around 7–8 ×10⁻⁶ /°C, whereas common furnace steels range from 11–17 ×10⁻⁶ /°C. This mismatch creates shear and bending stresses as temperatures rise.

In constrained assemblies, engineers often notice that plates crack near bolt holes or rigid clamps despite conservative thermal ramps. Post-analysis typically reveals that metal frames expanded faster, imposing in-plane compression on the ceramic. Even a restrained displacement of 0.2–0.4 mm over a 300 mm length can exceed tensile limits at plate edges when temperatures exceed 1300 °C.

Consequently, mechanical design must allow relative movement. Sliding interfaces, compliant pads, or clearance gaps often extend Alumina Plate life more effectively than increasing thickness, particularly in mixed-material assemblies.

Crack Initiation Under Combined Thermal and Mechanical Stress

Cracks in Alumina Plate rarely initiate at the center of uniform plates. Instead, they emerge at edges, corners, or contact points where stress concentration intersects thermal gradients. Combined thermal and mechanical stress can reduce effective fracture resistance by 30–50% compared with purely mechanical loading.

During pilot-scale reactor trials, engineers frequently detect early microcracks after 200–400 cycles, even when individual cycles remain within nominal limits. These cracks often align with support geometry or sharp fixture edges rather than with heater locations. Over time, repeated cycling causes stable cracks to propagate catastrophically during an otherwise routine run.

Therefore, crack prevention depends on managing stress concentration as much as on material selection. Edge geometry, support spacing, and load distribution directly influence crack initiation thresholds, especially under cyclic heating.

Summary of Mechanical Load Considerations

| Mechanical factor | Typical magnitude | Failure tendency | Mitigation strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static compressive stress (MPa) | 0.05–0.3 | Creep and sagging | Span reduction |

| Modulus reduction (%) | 20–35 | Increased deflection | Thickness tuning |

| CTE mismatch (×10⁻⁶ /°C) | 4–10 difference | Edge cracking | Sliding interfaces |

| Restrained displacement (mm) | 0.2–0.4 | Tensile fracture | Clearance allowance |

| Cycle-induced crack onset (cycles) | 200–400 | Progressive failure | Stress redistribution |

| Support contact stress | Localized | Crack initiation | Edge rounding |

Before geometry and support strategies are finalized, thermal shock behavior must be evaluated, because rapid temperature transitions remain the dominant cause of unexpected Alumina Plate fracture in heating systems.

Thermal Shock Behavior and Heating Ramp Sensitivity

Thermal shock occurs when temperature changes faster than heat can redistribute through the Alumina Plate thickness. Moreover, this imbalance creates transient tensile stress that exceeds ceramic fracture limits even when average temperatures remain acceptable. Consequently, heating and cooling rates often govern service life more strongly than peak temperature.

In industrial furnaces and lab-scale reactors, ramp sensitivity becomes critical during startup, shutdown, and emergency interruptions. Therefore, engineers must quantify not only allowable temperature limits but also permissible temperature gradients per unit time to prevent brittle failure.

Heating and Cooling Rate Thresholds

Heating and cooling rate thresholds define the maximum allowable temperature change per minute without inducing fracture. For Alumina Plate thicknesses between 5–15 mm, conservative ramp rates typically range from 2–5 °C/min below 800 °C, increasing to 5–10 °C/min at higher temperatures once thermal conductivity improves. Exceeding these rates elevates tensile stress near surfaces.

During qualification runs, engineers frequently observe that plates survive aggressive heating yet crack during rapid cooling. For instance, a controlled cool-down exceeding 15 °C/min through 600–400 °C often triggers edge cracks, even when heating rates were acceptable. This asymmetry occurs because thermal gradients reverse direction, placing the previously compressed surface into tension.

Therefore, cooling protocols deserve equal attention. Ramp symmetry and controlled cool-down below 800 °C significantly reduce thermal shock risk, particularly in plates subjected to cyclic operation.

Edge Geometry and Stress Concentration

Edge geometry amplifies or mitigates thermal shock sensitivity. Sharp corners act as stress concentrators where transient tensile stress accumulates. Even minor geometry differences can shift fracture thresholds by 20–30% under identical ramp conditions.

In furnace retrofits, engineers often find that replacing sharp-edged plates with chamfered or radiused edges extends service life dramatically without altering material grade. For example, introducing a 1–2 mm edge radius has been shown to delay crack initiation beyond 500 cycles in batch furnaces operating with ΔT of 300–350 °C per cycle.

Thus, geometry refinement offers a low-cost, high-impact mitigation strategy. Edge treatment should be considered a primary design parameter rather than a finishing detail, especially in shock-prone systems.

Plate Thickness Versus Thermal Shock Resistance

Thickness influences thermal shock resistance in competing ways. Thicker plates increase structural stiffness and load capacity; however, they also intensify through-thickness temperature gradients during rapid ramps. As thickness increases beyond 15–20 mm, allowable ramp rates often decrease unless compensated by slower heating schedules.

In pilot-scale heating systems, engineers frequently report that reducing thickness from 20 mm to 12 mm while maintaining support spacing improves shock tolerance without sacrificing mechanical stability. This improvement arises because thinner plates equilibrate temperature faster, reducing transient stress.

Consequently, thickness selection must balance load-bearing requirements against ramp sensitivity. Optimal thickness often emerges from thermal modeling rather than from conservative oversizing, particularly in systems with frequent cycling.

Summary of Thermal Shock Parameters

| Thermal shock parameter | Typical value | Failure impact | Engineering control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safe heating rate (°C/min) | 2–10 | Surface cracking | Ramp scheduling |

| Critical cooling zone (°C) | 800–400 | Edge fracture | Controlled cool-down |

| Edge radius (mm) | 1–2 | Stress reduction | Geometry refinement |

| Plate thickness (mm) | 5–20 | Gradient magnitude | Thickness optimization |

| Cycle ΔT (°C) | 250–400 | Fatigue accumulation | Cycle limitation |

| Crack onset cycles | 200–500 | Sudden failure | Stress mitigation |

Before advanced geometry optimization is discussed, it is necessary to clarify how Alumina Plate functions simultaneously as a structural element and an insulating barrier inside high-temperature heating systems.

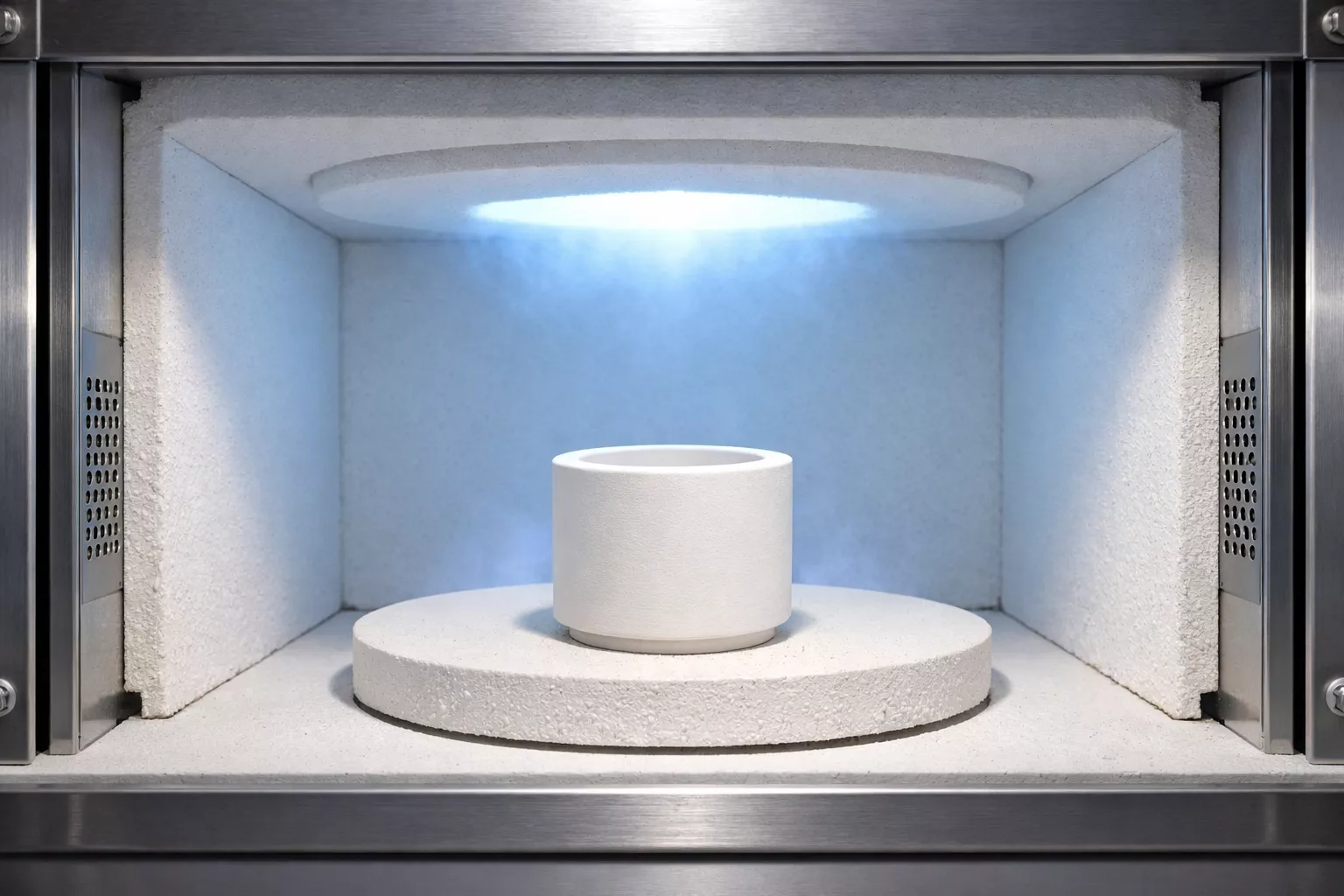

Alumina Plate as Structural and Insulating Components

Alumina Plate rarely serves a single function in industrial furnaces or reaction systems. Instead, it operates at the intersection of load-bearing support, thermal separation, and electrical isolation. Consequently, performance limitations often arise when one function is optimized without regard for the others.

-

Structural spacers in heating chambers

Alumina Plate is frequently used as a spacer supporting fixtures, heating elements, or reaction vessels. At temperatures above 1200 °C, compressive stiffness decreases, and load redistribution becomes significant. Therefore, plate placement and support spacing must account for time-dependent deformation rather than static strength alone. -

Electrical isolation at elevated temperatures

In resistance-heated furnaces and hybrid thermal systems, Alumina Plate isolates live components while operating at temperatures where polymers fail. Dielectric strength remains stable beyond 1000 °C; however, surface contamination and microcracks can reduce insulation margins. Consequently, cleanliness and surface integrity directly influence electrical safety. -

Support interfaces between hot and cold zones

Alumina Plate often bridges regions with large temperature differentials. This role introduces bending stress driven by thermal gradients across the plate surface. Accordingly, designers must allow controlled movement at interfaces to prevent constraint-induced cracking.

Together, these roles require balanced specification. Treating Alumina Plate as either purely structural or purely insulating often leads to premature failure, whereas integrated design extends service life and system reliability.

Before interaction effects are addressed, geometry and dimensional stability must be examined, because shape retention at temperature directly governs alignment, load transfer, and process repeatability.

Geometry Design and Dimensional Stability at High Temperature

Geometry determines how Alumina Plate responds once elastic behavior gives way to time-dependent deformation. Moreover, dimensional instability often manifests gradually, making it harder to detect until alignment drift or uneven heating appears. Consequently, geometry design must anticipate hot-state behavior rather than relying on cold-state measurements.

In industrial furnaces and high-temperature reactors, plates operate under combined bending, compression, and thermal gradients. Therefore, flatness retention, aspect ratio, and machining tolerances become functional parameters rather than cosmetic specifications.

Flatness Retention Under Long-Term Heating

Flatness retention reflects the ability of Alumina Plate to maintain planarity during prolonged dwell at elevated temperature. At 1400–1550 °C, even minor creep strain can translate into visible bowing over spans exceeding 300 mm. In continuous furnaces, deflection of 0.8–1.5 mm after 100–300 hours is commonly reported when geometry is not optimized.

During system validation, engineers often notice secondary effects before visible warpage. Uneven contact pressure, altered radiative exposure, and localized overheating typically precede measurable deformation. Consequently, flatness degradation can amplify thermal gradients, accelerating further distortion in a feedback loop.

Therefore, flatness specifications should be paired with service temperature and dwell duration. Hot-state flatness tolerance is a more meaningful criterion than room-temperature flatness, particularly for alignment-critical fixtures.

Aspect Ratio and Stress Redistribution

Aspect ratio influences how thermal and mechanical stress redistributes across the plate. Long, narrow plates concentrate bending stress along their length, while wide plates distribute stress more evenly but become sensitive to support placement. Ratios exceeding 5:1 frequently exhibit higher edge stress under identical loading.

In pilot reactor platforms, engineers have observed that reducing plate length by 10–15% while maintaining thickness significantly lowers mid-span stress without altering process capacity. This adjustment shifts stress distribution closer to supports, reducing crack initiation probability at free edges.

As a result, aspect ratio should be evaluated alongside support geometry. Moderate aspect ratios often outperform oversized plates, even when material grade remains unchanged.

Machining Tolerances Versus Thermal Distortion

Machining tolerances define cold-state accuracy, yet thermal distortion governs hot-state behavior. Alumina Plate machined to ±0.05 mm at room temperature may deviate beyond ±0.3 mm after extended heating if geometry promotes uneven expansion.

Engineers frequently encounter cases where tight tolerances increase failure risk by constraining thermal movement. For example, interference fits that appear precise during assembly can induce compressive stress exceeding ceramic limits once temperature rises above 1200 °C. Consequently, overly aggressive tolerances may shorten service life rather than improve performance.

Therefore, tolerance strategy must differentiate between locating features and free-expansion zones. Selective tolerance relaxation often improves reliability more effectively than uniform precision.

Summary of Geometry and Stability Factors

| Geometry factor | Typical range | High-temperature effect | Design priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plate span (mm) | 200–600 | Deflection sensitivity | High |

| Aspect ratio | 2:1–6:1 | Stress concentration | Medium |

| Hot-state flatness drift (mm) | 0.3–1.5 | Alignment loss | Critical |

| Thickness (mm) | 6–20 | Stiffness vs gradient | High |

| Machining tolerance (mm) | ±0.05–0.2 | Constraint stress | Medium |

| Dwell duration (h) | 20–300+ | Creep accumulation | High |

Before failure patterns are generalized, interaction effects must be examined, because Alumina Plate performance is strongly shaped by contact with refractory linings and metallic fixtures rather than by isolated material behavior.

Interaction with Refractory and Metallic Components

Alumina Plate rarely operates in isolation inside high-temperature heating systems. Instead, it interfaces continuously with refractories, metallic frames, and composite insulation structures. Moreover, these interfaces evolve as temperature rises, materials expand, and mechanical constraints shift. Consequently, interaction behavior often governs real service life more decisively than intrinsic ceramic properties.

In OEM furnace designs, interface assumptions made at room temperature frequently fail under hot conditions. Therefore, contact mechanics, relative motion, and chemical compatibility must be evaluated as part of system-level design rather than treated as installation details.

Contact Interfaces with Refractory Materials

Refractory materials surrounding Alumina Plate typically exhibit lower thermal conductivity and higher compliance. At temperatures above 1200 °C, many refractories undergo measurable creep, gradually increasing contact pressure on adjacent ceramic plates. This pressure redistribution can induce bending stress even when initial fits were generous.

During long-duration furnace trials, engineers often observe that plates crack along edges in contact with rigid refractory blocks rather than at free surfaces. In several installations, reducing refractory contact area by 15–25% through chamfering or spacing relieved stress concentration and extended plate life beyond 2× previous cycle counts. Therefore, interface geometry between alumina and refractory components plays a decisive role.

Accordingly, Alumina Plate should be allowed to slide or float against refractories whenever possible. Soft interfaces and controlled contact zones reduce constraint-driven fracture, especially during prolonged dwell.

Alumina Plate Against Metal Fixtures at High Temperature

Metal fixtures introduce a different challenge due to thermal expansion mismatch. Typical furnace steels expand at 11–17 ×10⁻⁶ /°C, compared with 7–8 ×10⁻⁶ /°C for alumina. As temperature increases, metal components grow faster, generating compressive stress on constrained ceramic plates.

In practice, engineers frequently encounter cracks near bolt holes, slots, or rigid clamps after 50–150 cycles, even when thermal ramps remain conservative. Post-failure analysis often shows that metal growth of 0.3–0.6 mm over moderate spans was sufficient to exceed tensile limits at ceramic edges. Consequently, rigid metal-ceramic fixation is a common root cause of premature failure.

Therefore, metal interfaces should incorporate clearance, slots, or compliant layers. Allowing differential expansion is more effective than increasing ceramic thickness, particularly in cyclic systems.

Chemical Compatibility at Interface Zones

Chemical interaction at interfaces can accelerate degradation without visible mechanical damage. Alkali vapors, silica dust, or metal oxides can react with alumina surfaces, forming low-melting boundary layers above 1300–1400 °C. These layers reduce friction predictability and may weaken surface integrity.

In mixed-use furnaces, engineers often notice plate discoloration or localized glazing after 100–300 hours, coinciding with changes in heating uniformity. Although the alumina core remains intact, surface reactions alter emissivity and contact behavior, indirectly increasing thermal gradients and stress.

Thus, interface chemistry must be controlled alongside mechanics. Clean furnace environments and compatible refractory selections significantly reduce secondary degradation mechanisms.

Summary of Interface Interaction Factors

| Interface aspect | Typical condition | Failure tendency | Design mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refractory contact pressure | Increases with dwell | Edge cracking | Reduced contact area |

| Metal CTE mismatch (×10⁻⁶ /°C) | 4–10 difference | Constraint fracture | Sliding interfaces |

| Restrained metal growth (mm) | 0.3–0.6 | Tensile overload | Clearance slots |

| Surface chemical films | Alkali or silica | Emissivity shift | Atmosphere control |

| Interface friction | Variable at temp | Stress localization | Compliant layers |

| Mixed-material assemblies | Common | Complex stress paths | System-level review |

Before selection logic is formalized, recurring failure patterns must be summarized, because these patterns reveal how Alumina Plate behaves under real furnace conditions rather than under idealized assumptions.

Failure Patterns Observed in Furnace Applications

Failure patterns in Alumina Plate applications tend to repeat across furnace types, regardless of scale. Moreover, these failures often develop progressively, giving early signals that are overlooked during routine operation. Consequently, recognizing characteristic patterns allows OEMs and process teams to intervene before catastrophic plate loss occurs.

-

Edge cracking after repeated cycles

Edge cracking is the most common failure mode in cyclic furnaces operating with ΔT of 250–400 °C. Cracks typically initiate at corners or contact points after 200–500 cycles, especially where plates are partially constrained. Although cracks may remain stable initially, continued cycling promotes propagation toward the center. Therefore, edge condition and support compliance are critical preventive measures. -

Mid-span sagging during prolonged high-temperature dwell

Sagging emerges in continuous or long-dwell furnaces above 1400 °C, where creep deformation accumulates over 100–300 hours. Plates remain intact but lose flatness, often by 0.8–1.5 mm across spans exceeding 300 mm. This deformation alters fixture alignment and heat distribution, indirectly triggering secondary failures. Consequently, creep resistance and span control dominate reliability in long-run systems. -

Surface degradation without visible fracture

Surface degradation appears as discoloration, glazing, or roughened patches after extended exposure to contaminated atmospheres. Although structural integrity remains, altered emissivity and friction change local heating patterns by 10–20%, increasing thermal gradients. As a result, plates may fail later through cracking driven by secondary stress rather than by chemical attack itself.

Collectively, these patterns show that Alumina Plate rarely fails abruptly without warning. Most failures evolve through identifiable stages, enabling predictive maintenance when engineers know what to monitor.

Before customization pathways are introduced, selection logic must be consolidated, because OEMs and system integrators require a repeatable decision framework rather than isolated material facts.

Selection Logic for OEM and System Integrators

Selection logic translates operating envelopes, material architecture, and mechanical interactions into actionable specification choices. Moreover, effective selection reduces trial-and-error iterations during commissioning. Consequently, Alumina Plate decisions should follow a structured path that aligns process demands with realistic design margins.

In furnace and high-temperature system projects, selection failures often stem from optimizing a single parameter, such as purity or thickness, while ignoring system interactions. Therefore, the following logic emphasizes balance rather than maximum values.

Matching Alumina Grade to Heating Profile

Heating profiles determine which alumina grade performs reliably. Short-cycle furnaces with peak temperatures near 1400 °C often tolerate 96–99% Al₂O₃, provided ramp rates remain controlled. By contrast, long-dwell processes above 1450 °C benefit from ≥99% Al₂O₃, which delays grain-boundary softening and creep.

During pilot line expansion, engineers frequently upgrade grade without altering geometry, yet still encounter sagging. This outcome illustrates that grade selection must reflect both temperature and dwell duration. Heating profile duration is as decisive as peak temperature, especially for continuous systems.

Thickness and Geometry Trade-Off Strategy

Thickness improves stiffness but increases thermal gradients. In practice, plates between 8–15 mm often represent an optimal balance for industrial furnaces, combining sufficient load capacity with manageable shock sensitivity. Excessive thickness beyond 20 mm typically demands slower ramps to avoid cracking.

Engineers routinely discover that reducing thickness while improving support spacing yields better performance than simply oversizing plates. For example, reducing span by 20% often lowers bending stress more effectively than increasing thickness by 5 mm. Therefore, geometry optimization should precede thickness escalation.

When Standard Plates Become Insufficient

Standard Alumina Plate formats meet many applications; however, complex load paths, extreme gradients, or constrained assemblies often exceed standard assumptions. In such cases, custom geometry, tailored edge treatment, or material grading becomes necessary.

OEM teams often reach this conclusion after repeated plate replacement during validation. Rather than iterating blindly, defining custom solutions based on observed failure modes accelerates stabilization. Customization is justified when system behavior consistently violates standard plate assumptions, not merely when failures occur.

Summary of Selection Decision Factors

| Selection factor | Typical choice range | System implication | Decision emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alumina purity (%) | 96–99.5 | Creep resistance | Profile-dependent |

| Plate thickness (mm) | 8–20 | Shock vs stiffness | Balanced |

| Support span (mm) | 200–500 | Deflection control | High |

| Ramp rate (°C/min) | 2–10 | Crack avoidance | Critical |

| Dwell duration (h) | 0.5–300+ | Deformation risk | High |

| Custom geometry need | Low to high | Reliability margin | Case-driven |

Before concluding system-level performance, customization pathways must be clarified, because standardized formats rarely align perfectly with real furnace constraints and process objectives.

Custom Alumina Plate Solutions with ADCERAX

Custom Alumina Plate solutions become valuable when operating envelopes, load paths, and interface conditions exceed generic assumptions. Moreover, customization is most effective when driven by engineering data rather than by dimensional preference alone. Consequently, ADCERAX approaches customization as a structured technical collaboration rather than a catalog extension.

In furnace and high-temperature system projects, ADCERAX typically begins with drawing-based evaluation. Heating profiles, support geometry, and atmosphere exposure are reviewed simultaneously, allowing material grade, thickness, and edge treatment to be aligned with dominant risk factors. This front-loaded engineering step reduces redesign loops and shortens qualification timelines.

-

Drawing-based evaluation for heating systems

ADCERAX analyzes customer drawings by correlating span length, contact points, and thermal gradients with expected stress distribution. For example, plates operating above 1450 °C with spans exceeding 350 mm often benefit from localized thickness adjustment or modified support geometry. This targeted refinement improves hot-state flatness without increasing overall mass. -

Material and geometry optimization suggestions

Rather than defaulting to higher purity, ADCERAX recommends grade upgrades only when dwell duration or atmosphere demands justify it. Geometry refinements such as edge chamfers of 1–2 mm or selective tolerance relaxation are introduced to mitigate thermal shock and constraint stress. Field feedback shows that these adjustments can extend service life by 30–60% in cyclic furnaces. -

One-stop manufacturing inspection and delivery support

ADCERAX integrates material selection, forming, sintering, precision machining, and inspection into a unified workflow. Density verification, dimensional checks, and surface condition assessment ensure consistency across production batches. As a result, OEMs receive Alumina Plate components that behave predictably from prototype validation through series deployment.

Accordingly, ADCERAX functions as an engineering partner that converts furnace-specific constraints into reliable Alumina Plate solutions, supporting both experimental platforms and industrial-scale equipment.

Before closing the discussion, long-term behavior must be evaluated, because Alumina Plate delivers value in heating systems only when performance remains stable across extended operating life.

Long-Term Reliability and System-Level Value

Long-term reliability reflects how Alumina Plate behaves after hundreds of hours and repeated cycles, rather than how it performs during initial qualification. Moreover, reliability at system level emerges from stability in geometry, insulation function, and interface behavior under cumulative thermal exposure. Consequently, lifecycle value depends on predictability rather than peak performance.

In industrial furnaces and high-temperature reactors, well-specified Alumina Plate typically maintains functional integrity over 10³–10⁴ hours when operating envelopes and interfaces are respected. During this period, deformation progresses slowly, surface conditions stabilize, and crack initiation remains suppressed. By contrast, marginal designs often fail abruptly after long periods of apparent stability, creating unexpected downtime.

From a system integration perspective, reliable Alumina Plate reduces recalibration frequency, fixture adjustment, and spare inventory turnover. OEMs benefit from consistent hot-zone geometry, while process teams gain repeatable thermal profiles across batches. Therefore, Alumina Plate contributes to overall equipment effectiveness through reliability continuity rather than through isolated material metrics.

Summary of Long-Term Performance Indicators

| Lifecycle indicator | Typical stable outcome | System benefit | Engineering implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating duration (h) | 1,000–10,000 | Reduced downtime | Predictable maintenance |

| Hot-state flatness drift (mm) | ≤1.0 | Stable alignment | Consistent heat distribution |

| Crack initiation cycles | >500 | Extended service life | Lower replacement rate |

| Surface condition change | Gradual, limited | Stable emissivity | Uniform processing |

| Interface stability | No progressive locking | Stress mitigation | Reliable assembly |

| Qualification repeatability | High | Faster scale-up | Reduced validation effort |

Conclusion

In conclusion, Alumina Plate succeeds in high-temperature heating systems when thermal envelopes, material architecture, mechanical load paths, and interface behavior are addressed as a unified engineering problem.

For industrial furnaces and high-temperature systems requiring stable and repeatable performance, ADCERAX provides engineering-driven Alumina Plate customization aligned with real operating conditions.

FAQ

What temperature range is suitable for Alumina Plate in industrial furnaces

Most industrial Alumina Plate applications operate reliably between 1200 and 1600 °C, depending on purity, dwell duration, and mechanical loading.

How does dwell time affect Alumina Plate selection

Extended dwell above 1400 °C increases creep risk, making higher purity and optimized geometry more important than peak temperature alone.

Is thicker Alumina Plate always safer at high temperature

Not necessarily. Increased thickness improves stiffness but also intensifies thermal gradients, which can reduce thermal shock tolerance.

When should custom Alumina Plate be considered

Customization becomes appropriate when standard plates exhibit repeated cracking, warping, or interface-related failures despite controlled operating conditions.

References: