Alumina Trays are often treated as simple containers, yet hidden failures inside powder-based thermal lines repeatedly erode yield, stability, and process predictability across industrial operations.

Alumina Saggar functions as a structural and thermal interface between powder materials and thermal environments. This article consolidates material science, structural mechanics, and process experience to explain how Alumina Saggar directly governs powder stability, contamination risk, and lifecycle performance in powder-based thermal manufacturing.

Furthermore, understanding Alumina Saggar requires moving beyond catalog specifications toward a system-level interpretation of how material properties, geometry, and repeated thermal exposure interact with powder behavior under industrial conditions.

Before addressing application-level behavior, it is necessary to establish how the intrinsic material characteristics of Alumina Saggar influence its stability, durability, and compatibility with powder-based thermal processes.

Material Foundations of Alumina Saggar

Alumina Saggar performance originates from its material composition and microstructural configuration rather than from external usage conditions alone. Moreover, powder-based processes amplify subtle material differences because repeated thermal cycling and powder contact expose latent weaknesses over time. Consequently, a clear material foundation is essential for interpreting later deformation, contamination, and lifetime behavior.

Alumina Composition Ranges and Phase Stability

Alumina Saggar is commonly produced with Al₂O₃ contents ranging from 95% to above 99.5%, and each composition introduces distinct thermal and chemical behaviors. In practice, higher alumina content reduces glassy phases at grain boundaries, which significantly improves phase stability above 1,400 °C under repeated heating cycles.

In powder manufacturing environments, operators often observe that 96% alumina saggar maintains structural integrity for 20–30% fewer cycles compared to ≥99% grades when exposed to identical thermal schedules. For instance, during oxide powder calcination, lower-purity saggar tends to soften microscopically after 200–300 cycles, even when macroscopic cracks remain absent.

Therefore, composition selection is not merely a temperature rating decision but a stability strategy that directly affects saggar lifespan and powder consistency.

Grain Structure Porosity and Bulk Density Effects

Grain size distribution and open porosity determine how Alumina Saggar interacts with powder materials at elevated temperatures. Typically, industrial saggar exhibits bulk densities between 3.6–3.9 g/cm³, with open porosity ranging from 3% to 8%, depending on forming and sintering routes.

In powder-based lines, saggar with porosity exceeding 6% shows measurable powder infiltration after 50–100 cycles, particularly with fine powders below 5 µm particle size. During long production runs, engineers frequently report gradual weight gain of saggar bodies, indicating internal powder penetration rather than surface contamination.

Consequently, microstructural density is directly tied to contamination control and long-term cleaning feasibility.

Thermal Expansion Behavior Under Repeated Cycles

The linear thermal expansion coefficient of alumina, typically around 7.5–8.2 ×10⁻⁶ /K, appears modest; however, repeated thermal cycling magnifies its mechanical implications. Even small expansion mismatches between saggar body, powder load, and furnace supports accumulate stress during hundreds of heat-up and cool-down cycles.

In production environments, saggar subjected to daily cycles between ambient temperature and 1,300–1,500 °C often begins to exhibit edge warping after 150–250 cycles, especially when combined with uneven powder loading. Operators often misattribute this deformation to handling damage, although the root cause lies in thermal expansion fatigue.

Accordingly, thermal expansion behavior must be evaluated across the entire operational cycle count rather than at peak temperature alone.

Summary Table: Core Material Parameters Governing Alumina Saggar Performance

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on Powder-Based Manufacturing |

|---|---|---|

| Alumina Content (%) | 95 – ≥99.5 | Higher purity improves phase stability and cycle life |

| Bulk Density (g/cm³) | 3.6 – 3.9 | Higher density reduces powder infiltration |

| Open Porosity (%) | 3 – 8 | Lower porosity limits contamination and eases cleaning |

| Thermal Expansion (×10⁻⁶ /K) | 7.5 – 8.2 | Governs deformation risk under repeated cycles |

| Stable Cycle Count (cycles) | 200 – 600+ | Depends on purity, porosity, and thermal profile |

Once material fundamentals are established, attention naturally shifts toward how Alumina Trays behave as functional interfaces within powder-based thermal workflows, where isolation, support, and heat mediation occur simultaneously.

Functional Role of Alumina Saggar in Powder Handling

Alumina Saggar operates as more than a passive container in powder-based thermal manufacturing. Instead, it acts as a multifunctional interface that separates powders from furnace environments while stabilizing geometry and moderating heat transfer. Consequently, its functional role directly influences powder integrity, batch consistency, and process repeatability across repeated production cycles.

Powder Isolation and Chemical Inertness

Alumina Saggar provides a chemically inert boundary between powder materials and surrounding furnace components. In oxide and mixed-oxide powder systems, alumina exhibits negligible chemical interaction below 1,500–1,600 °C, which significantly reduces unintended phase formation or impurity uptake during extended thermal exposure.

In industrial powder lines, engineers often observe that saggar materials with alumina purity above 99% limit detectable contamination to below 0.01 wt% after 100+ thermal cycles, whereas lower-purity containers may introduce trace silicate or alkali phases earlier. During routine production, this isolation function becomes critical when powders are reused or recycled, since cumulative contamination can otherwise exceed specification thresholds.

Therefore, chemical inertness is not an abstract material property but a practical control mechanism for maintaining powder chemistry over long production horizons.

Load Support and Geometric Constraint

Beyond isolation, Alumina Saggar must support powder loads without inducing mechanical instability. Typical powder bed loads range from 1 to 6 kg per saggar, depending on footprint and layer thickness, creating sustained compressive stress during high-temperature dwell periods.

In practice, saggar designs with insufficient bottom thickness or uneven wall stiffness exhibit measurable deflection after 200–300 cycles, even when no cracking is present. Production teams frequently report subtle powder redistribution caused by saggar flexing, which leads to localized density gradients and inconsistent sintering behavior across a single batch.

Accordingly, effective load support transforms Alumina Saggar into a structural fixture that preserves powder geometry under thermal and mechanical stress.

Thermal Mass and Heat Flow Moderation

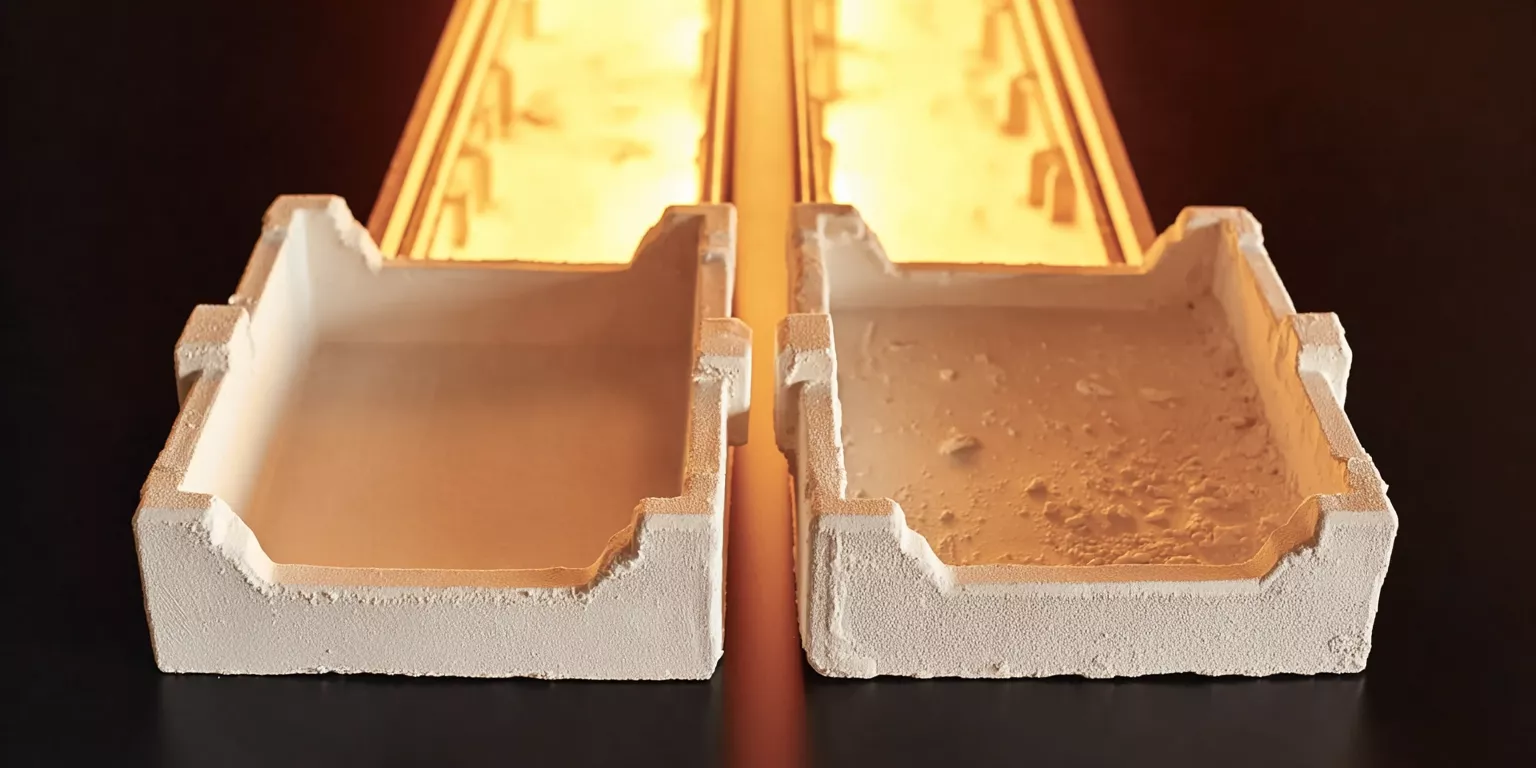

Alumina Saggar also influences how heat is absorbed, stored, and released around powder beds. With specific heat capacity near 0.88 kJ·kg⁻¹·K⁻¹, alumina moderates rapid temperature fluctuations and dampens transient thermal gradients within the powder mass.

During controlled production trials, operators often note that saggar with higher thermal mass reduces peak temperature differentials inside powder beds by 10–18 °C compared to thinner or lower-density containers. This moderation improves thermal uniformity, especially during ramp-up and cool-down stages where powder cracking or abnormal grain growth may occur.

As a result, thermal mass is not a drawback but a stabilizing factor that enhances powder processing consistency.

Summary Table: Functional Contributions of Alumina Saggar in Powder Handling

| Functional Aspect | Quantitative Indicator | Impact on Powder Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Isolation | Contamination ≤0.01 wt% after 100 cycles | Preserves powder chemistry |

| Load Capacity | 1–6 kg powder load per saggar | Maintains powder geometry |

| Structural Stability | Deflection onset after 200–300 cycles | Prevents density gradients |

| Thermal Mass Effect | 10–18 °C gradient reduction | Improves heat uniformity |

| Heat Capacity (kJ·kg⁻¹·K⁻¹) | ~0.88 | Dampens transient fluctuations |

After clarifying the functional role of Alumina Trays in powder handling, it becomes necessary to examine how direct and prolonged interaction between powders and saggar surfaces shapes contamination risk, stability, and long-term usability.

Interaction Between Powder Materials and Alumina Saggar

Alumina Saggar interacts continuously with powder materials throughout thermal cycles, and this interaction governs contamination behavior, surface stability, and long-term performance. Furthermore, powder characteristics such as particle size, chemical composition, and volatility amplify surface-level phenomena that are otherwise negligible in bulk ceramic applications. Consequently, understanding these interactions is essential for predicting saggar behavior in powder-based thermal manufacturing.

Surface Contact and Powder Adhesion Mechanisms

Powder adhesion to Alumina Saggar surfaces originates from a combination of mechanical interlocking1 and thermally activated surface forces2. In practice, powders with median particle sizes below 10 µm exhibit increased contact area, which enhances van der Waals attraction and promotes partial sintering at contact points above 900–1,100 °C.

During routine production, engineers often notice that repeated cycles lead to localized powder build-up along saggar corners and edges, even when bulk powder appears free-flowing. After approximately 80–120 cycles, these adhered regions harden into thin ceramic layers that resist simple mechanical removal and gradually alter surface roughness.

Therefore, powder adhesion is a cumulative phenomenon that evolves with cycle count rather than an isolated cleanliness issue.

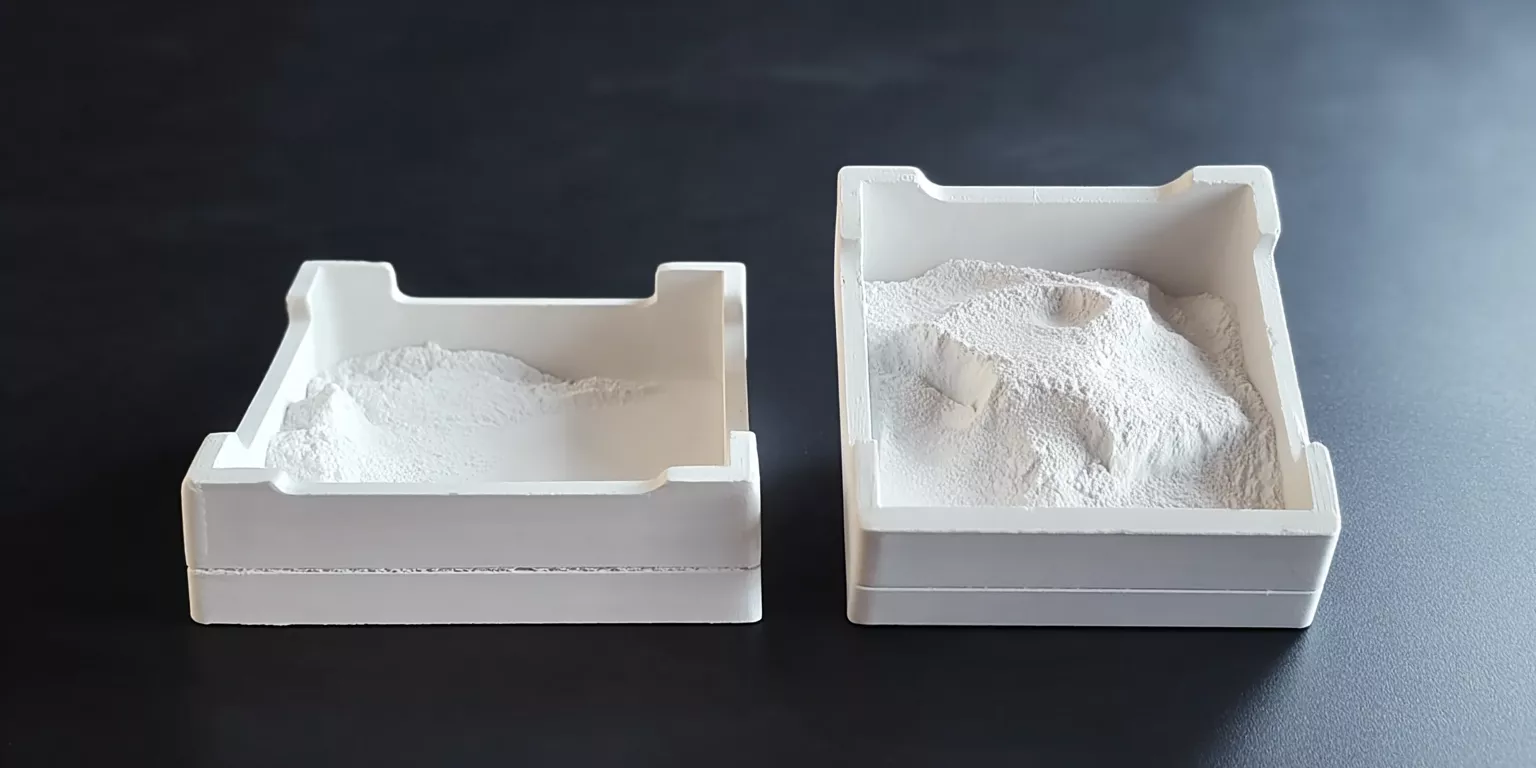

Infiltration Risks and Open Pore Transport

Beyond surface adhesion, fine powders can infiltrate the open pore network of Alumina Saggar during high-temperature exposure. Saggar with open porosity exceeding 5% allows capillary-driven penetration when powder particle sizes fall below 5 µm, particularly under long dwell times above 1,200 °C.

Field observations show that infiltrated powder can migrate 1–3 mm beneath the saggar surface after 100–150 cycles, creating internal contamination zones that cannot be fully removed by surface cleaning. Operators often detect this condition indirectly through incremental saggar weight gain or altered thermal response rather than visible surface changes.

As a result, infiltration transforms saggar from a reusable tool into a progressive contamination source if porosity control is insufficient.

Chemical Compatibility Across Common Powder Systems

Chemical compatibility between Alumina Saggar and powder systems depends on both temperature and powder chemistry. Oxide powders such as alumina, zirconia, and spinel typically remain chemically stable in contact with alumina up to 1,500 °C, with negligible interdiffusion over standard dwell times.

However, composite or doped powders containing alkali oxides, borates, or fluxing agents can react with alumina surfaces at temperatures as low as 1,100–1,250 °C. In industrial settings, this interaction manifests as localized glazing or surface vitrification after 60–100 cycles, which accelerates further powder adhesion and complicates cleaning.

Accordingly, compatibility assessment must consider not only base powder composition but also minor additives that influence interfacial reactions.

Summary Table: Powder–Saggar Interaction Mechanisms and Consequences

| Interaction Mechanism | Quantitative Threshold | Operational Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Adhesion | <10 µm powder size; ≥900 °C | Progressive surface roughening |

| Partial Sintering | ≥1,100 °C at contact points | Hardened residue formation |

| Pore Infiltration Depth | 1–3 mm after 100–150 cycles | Internal contamination |

| Porosity Sensitivity (%) | >5% open porosity | Irreversible powder uptake |

| Chemical Reaction Onset (°C) | 1,100–1,250 | Surface vitrification |

Furthermore, once powder–surface interactions are understood, structural geometry emerges as the next controlling variable, because even chemically stable Alumina Trays can fail prematurely if geometric stress distribution is poorly managed.

Structural Geometry of Alumina Saggar for Powder Stability

Alumina Saggar geometry governs how mechanical load, thermal expansion, and handling forces are distributed during powder-based thermal operations. Moreover, geometric decisions determine whether stresses remain diffuse or concentrate at predictable failure points. Consequently, structural design transforms Alumina Saggar from a generic container into a process-stabilizing fixture.

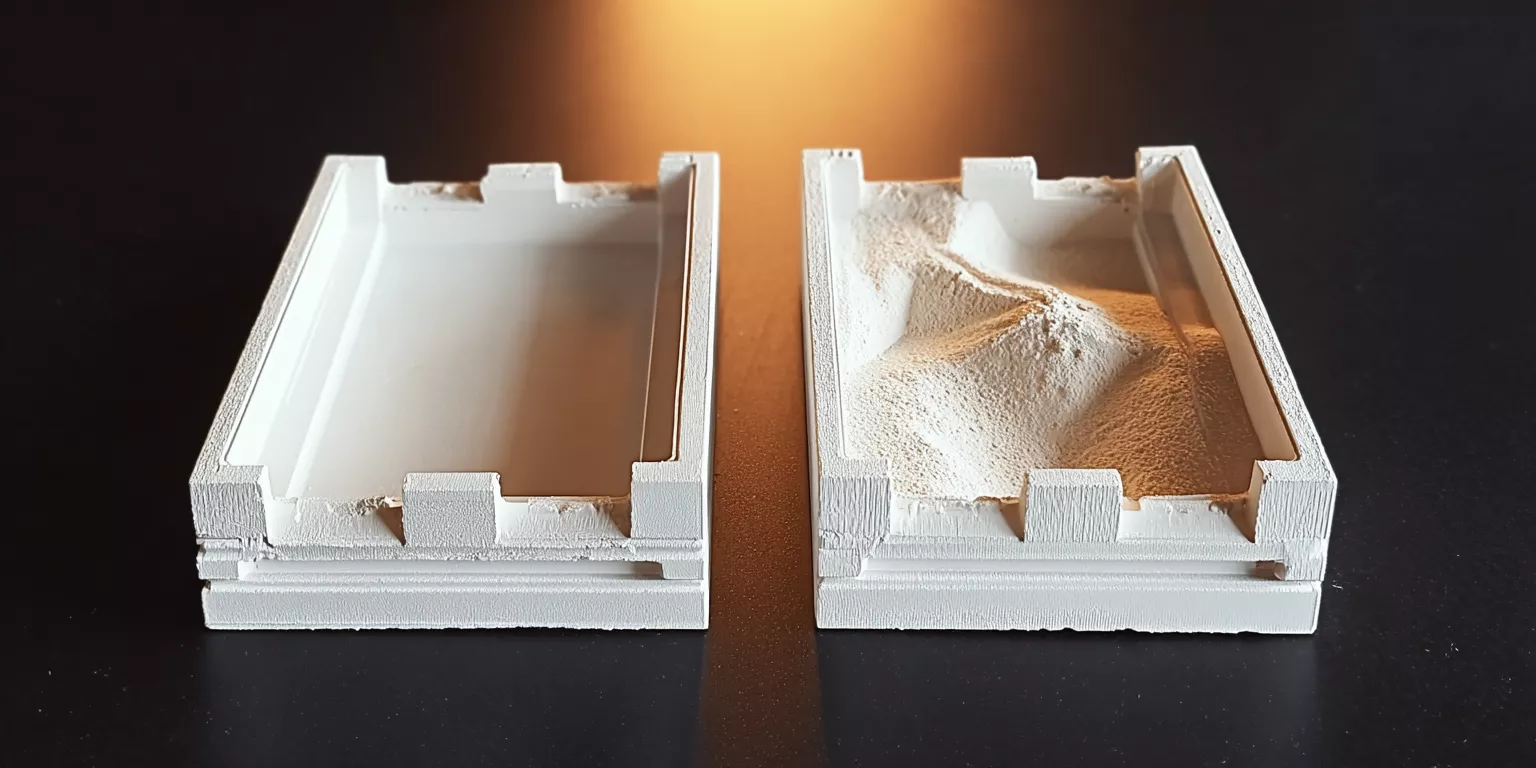

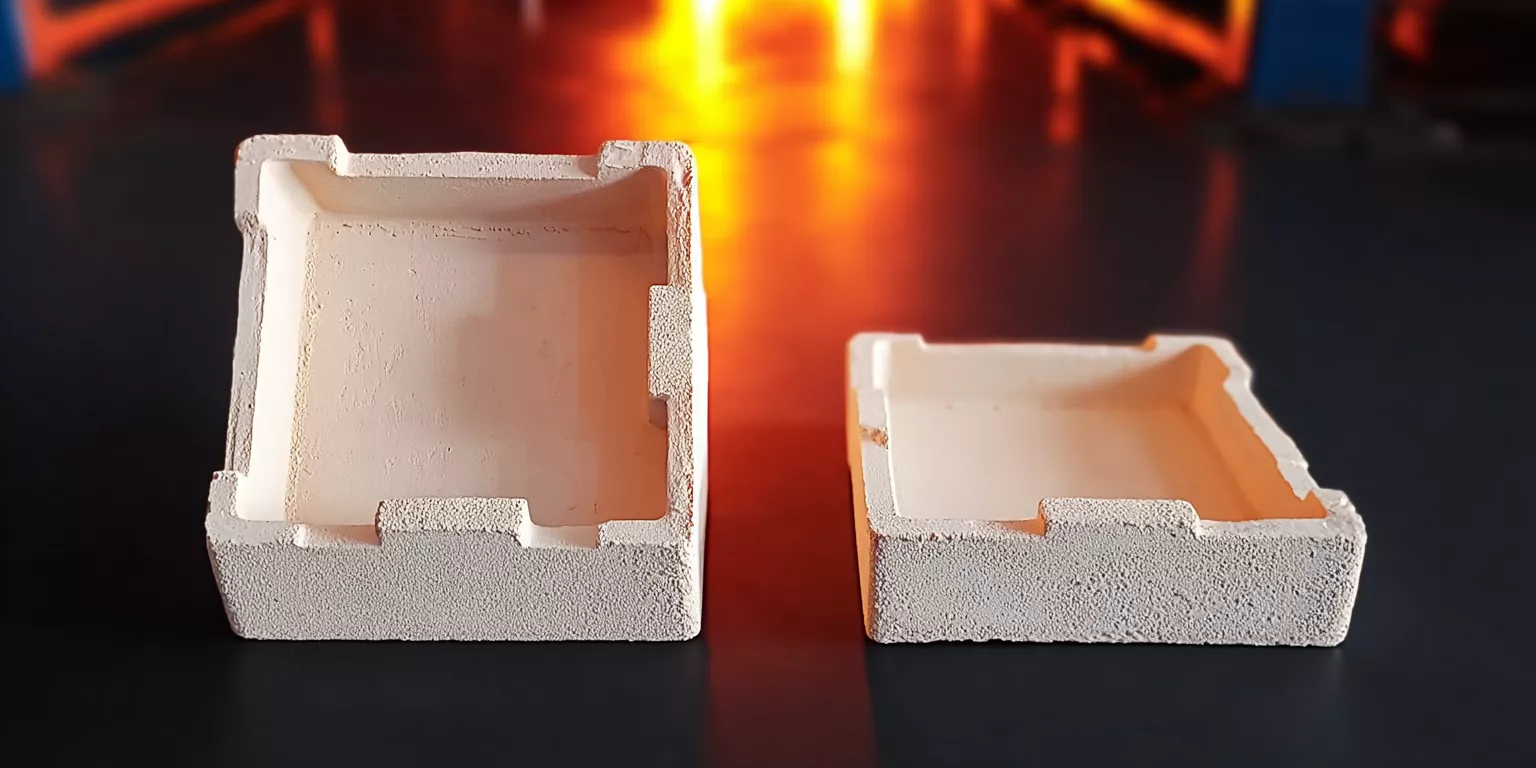

Wall Thickness Bottom Thickness and Stress Distribution

Wall and bottom thickness establish the primary load-bearing framework of Alumina Saggar. In powder applications, bottom thickness typically ranges from 6 to 15 mm, while side walls commonly fall between 5 and 12 mm, depending on footprint and powder mass.

In practice, saggar with insufficient bottom thickness relative to wall height develops bending stress during high-temperature dwell, especially when supporting powder loads above 3 kg. Production engineers often observe that saggar bottoms thinner than 7 mm begin to exhibit measurable center deflection after 180–250 cycles, even without visible cracking. Conversely, excessive thickness increases thermal gradients, which can elevate edge stress during heating and cooling.

Therefore, balanced thickness ratios are essential to distribute compressive and tensile stresses evenly across repeated cycles.

Corner Radii Edge Profiles and Crack Suppression

Sharp internal and external corners act as stress concentrators under thermal expansion and mechanical handling. Alumina Saggar designs with internal corner radii below 2 mm show crack initiation rates up to 40% higher than designs using radii of 4–6 mm, based on cycle-based inspection records from powder lines.

During routine handling, operators frequently notice that microcracks originate at corner intersections following rapid cool-down phases below 600 °C. Over time, these cracks propagate incrementally, often remaining invisible until sudden fracture occurs after 300–400 cycles. Rounded edge profiles reduce peak tensile stress and slow crack growth even when thermal ramps are unchanged.

Accordingly, corner geometry is one of the most effective passive design controls for extending saggar service life.

Notches Slots and Handling Features in Powder Lines

Notches and slots are increasingly integrated into Alumina Saggar to support automated handling and controlled stacking. Typical notch widths range from 8 to 15 mm, with depths of 4–8 mm, allowing mechanical grippers or positioning rails to engage reliably.

In powder-based production lines, saggar equipped with symmetrically placed notches demonstrate 15–25% lower handling-related damage rates compared to smooth-walled designs. Engineers report improved repeatability in stack alignment and reduced edge chipping during loading and unloading cycles exceeding 1,000 handling events.

Thus, handling features are not auxiliary details but structural elements that directly influence powder stability and operational consistency.

Summary Table: Structural Geometry Parameters Influencing Alumina Saggar Stability

| Geometry Parameter | Typical Range | Stability Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Bottom Thickness (mm) | 6 – 15 | Controls load deflection |

| Wall Thickness (mm) | 5 – 12 | Governs sidewall rigidity |

| Internal Corner Radius (mm) | 4 – 6 | Reduces crack initiation |

| Notch Width (mm) | 8 – 15 | Improves handling accuracy |

| Deflection Onset (cycles) | 180 – 250 | Indicates geometry imbalance |

Once geometric stress distribution is optimized, long-term reliability still depends on how Alumina Trays respond to repeated thermal exposure, where fatigue and gradual deformation emerge as dominant failure drivers.

Thermal Cycling Fatigue and Shape Retention

Thermal cycling subjects Alumina Saggar to alternating tensile and compressive stresses that accumulate gradually rather than causing immediate failure. Furthermore, powder-based thermal manufacturing often involves daily or continuous cycling, which amplifies fatigue mechanisms even when peak temperatures remain within nominal limits. Consequently, shape retention over hundreds of cycles becomes a more critical metric than short-term strength.

Crack Initiation Under Repeated Heating and Cooling

Crack initiation in Alumina Saggar typically begins at microstructural discontinuities exposed to cyclic thermal gradients. In industrial powder lines, temperature ramps between ambient conditions and 1,200–1,500 °C repeated 1–3 times per day generate tensile stress during cooling, particularly below 700 °C, where thermal gradients steepen.

Experienced operators often report that initial microcracks appear after 120–200 cycles, commonly near corners or thickness transitions, even when heating rates are well controlled. These cracks rarely propagate catastrophically at first; instead, they lengthen incrementally by tens of micrometers per cycle, remaining undetected during routine visual inspection.

Therefore, crack initiation is best understood as a cumulative fatigue process rather than an isolated thermal shock event.

Creep Deformation Under Sustained Load

At elevated temperatures, Alumina Saggar experiences time-dependent deformation under constant load, commonly referred to as creep. When powder loads exceed 2–4 kg per saggar and dwell temperatures remain above 1,300 °C for extended periods, creep strain accumulates even in high-purity alumina bodies.

In practice, saggar subjected to continuous dwell times of 4–8 hours per cycle often shows measurable permanent deformation after 150–250 cycles. Production teams frequently notice this as gradual loss of flatness rather than visible sagging, which subtly alters powder bed thickness and compromises thermal uniformity across batches.

As a result, creep deformation represents a silent but predictable contributor to shape loss in long-running powder operations.

Predictable Failure Patterns in Industrial Use

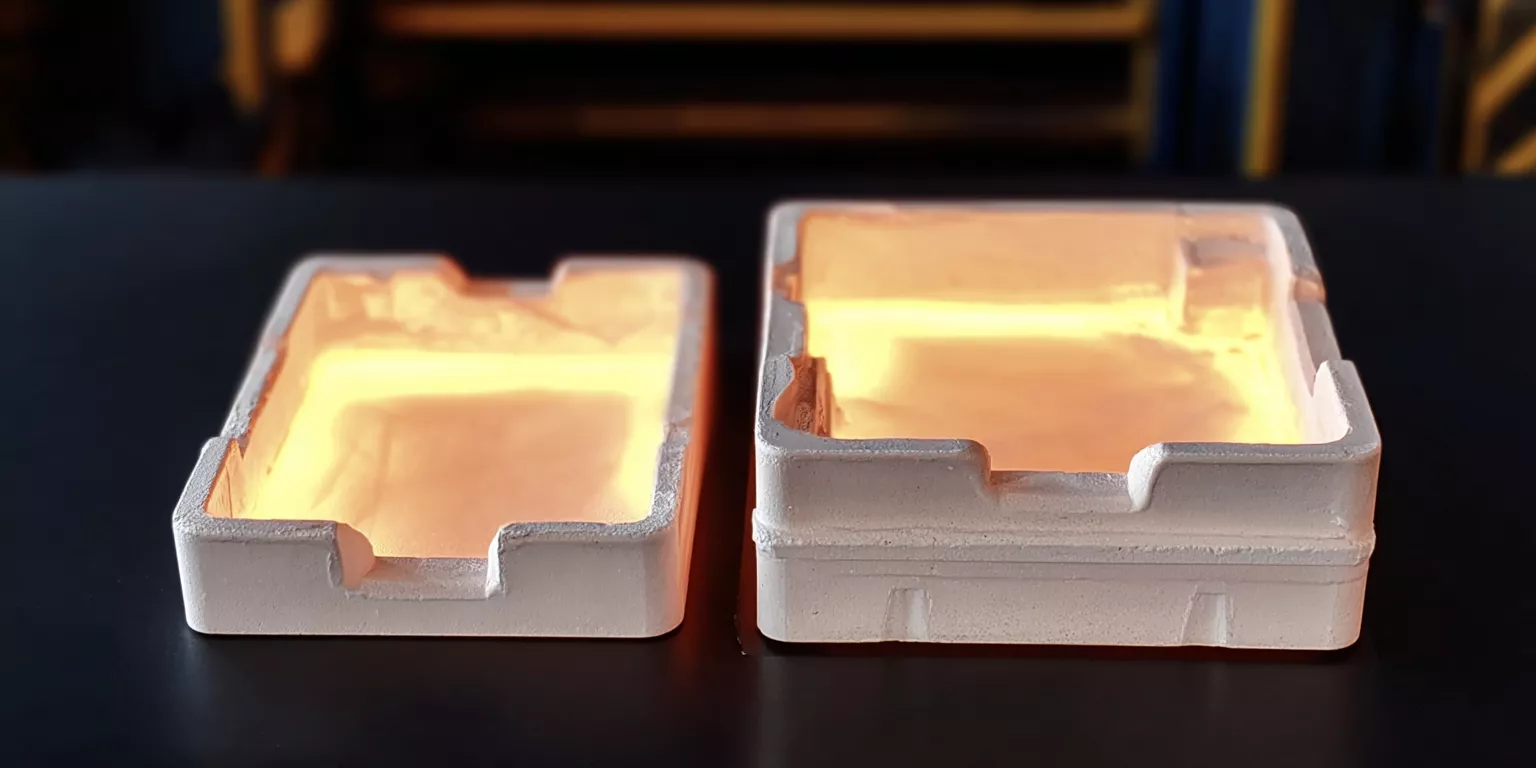

Although failure appears random to operators, Alumina Saggar degradation follows repeatable patterns tied to cycle count and load history. Field data collected across powder-based lines indicate that saggar typically transitions through three stages: stable operation, progressive distortion, and accelerated failure.

During stable operation, saggar maintains geometry for the first 100–150 cycles with minimal change. Subsequently, distortion accumulates gradually over the next 100–200 cycles, often accompanied by microcracking. Finally, once deformation exceeds 0.5–1.0 mm in critical regions, crack propagation accelerates, leading to sudden fracture or unacceptable dimensional drift.

Accordingly, recognizing these patterns enables proactive replacement planning before unplanned downtime occurs.

Summary Table: Thermal Fatigue and Shape Retention Characteristics

| Fatigue Parameter | Observed Range | Operational Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Thermal Cycles | 1 – 3 | Governs fatigue accumulation |

| Crack Initiation (cycles) | 120 – 200 | Early fatigue indicator |

| Dwell Temperature (°C) | ≥1,300 | Drives creep deformation |

| Permanent Deformation (mm) | 0.5 – 1.0 | Signals end-of-life phase |

| Typical Service Life (cycles) | 250 – 450 | Depends on load and geometry |

After understanding how thermal fatigue governs long-term shape retention, operational stability increasingly depends on how powders are loaded, arranged, and handled within Alumina Trays throughout repeated production cycles.

Loading Methods and Powder Arrangement Strategies

Alumina Saggar performance in powder-based thermal manufacturing is strongly influenced by loading methodology rather than material properties alone. Moreover, powder arrangement determines heat distribution, mechanical stress paths, and handling repeatability during high-frequency production. Consequently, loading strategies transform Alumina Saggar from a static container into an active process-control component.

Powder Bed Thickness and Heat Uniformity

Powder bed thickness directly affects internal heat transfer and temperature uniformity within the saggar. In industrial operations, typical powder bed thickness ranges from 10 to 40 mm, depending on particle size, thermal conductivity, and desired reaction kinetics.

Production engineers often observe that powder beds exceeding 30 mm exhibit internal temperature differentials of 15–25 °C during ramp-up phases, even when furnace temperature uniformity is tightly controlled. By contrast, thinner beds below 20 mm generally maintain gradients within 8–12 °C, reducing the risk of partial sintering or uneven phase development across the batch.

Therefore, controlling powder bed thickness is a primary lever for achieving consistent thermal exposure and reproducible powder properties.

Stacking Density and Airflow Paths

When Alumina Saggar is stacked inside furnaces, vertical spacing and airflow pathways become critical for thermal equilibrium. Common stacking clearances range from 8 to 20 mm, allowing convective heat flow while maintaining structural stability.

In continuous powder lines, saggar stacks with insufficient airflow clearance often develop localized hot spots, leading to uneven powder reactions after 50–80 cycles. Operators frequently report that introducing controlled gaps or staggered stacking patterns reduces batch-to-batch variability by approximately 20–30%, based on internal quality metrics.

Accordingly, stacking density must balance furnace capacity with predictable airflow and heat transfer behavior.

Mechanical Handling and Automation Compatibility

Modern powder-based manufacturing increasingly relies on automated handling systems, which impose repeatable mechanical loads on Alumina Saggar. Typical automated gripping forces range from 50 to 150 N, depending on saggar mass and handling speed.

In practice, saggar designs incorporating symmetrical handling features demonstrate 20–35% lower edge damage rates over 1,000+ handling cycles compared to smooth-walled alternatives. Engineers often recount early production phases where manual handling masked alignment issues that later caused frequent chipping once automation was introduced.

Thus, compatibility with mechanical handling is not optional but integral to sustaining high-throughput powder production.

Summary Table: Loading and Arrangement Parameters Affecting Powder Stability

| Loading Parameter | Typical Range | Process Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Powder Bed Thickness (mm) | 10 – 40 | Controls thermal uniformity |

| Internal Temperature Gradient (°C) | 8 – 25 | Influences powder consistency |

| Stacking Clearance (mm) | 8 – 20 | Enables airflow and heat transfer |

| Handling Force (N) | 50 – 150 | Affects edge durability |

| Damage Reduction with Features (%) | 20 – 35 | Improves handling reliability |

Furthermore, after loading and handling practices are stabilized, long-term usability of Alumina Trays depends heavily on how effectively contamination is removed without accelerating structural degradation.

Cleaning Regeneration and Contamination Control

Cleaning strategy directly influences the usable lifetime of Alumina Saggar in powder-based thermal manufacturing. Moreover, inappropriate regeneration methods often shorten service life more than thermal exposure itself. Consequently, contamination control must balance cleanliness with structural preservation across repeated cycles.

Residual Powder Removal Without Structural Damage

Residual powder removal is most effective when mechanical and thermal stresses are minimized. In practice, light mechanical brushing combined with controlled thermal burn-off below 900 °C removes loosely bonded powder without inducing microcracks.

Experienced production teams report that aggressive scraping increases surface roughness by 15–25% after 30–50 cleaning cycles, which subsequently accelerates powder adhesion during later runs. By contrast, gentler removal methods maintain surface integrity and delay adhesion onset beyond 120 cycles.

Therefore, cleaning intensity should be matched to contamination severity rather than applied uniformly.

Chemical Cleaning Versus Thermal Burn-Off

Chemical cleaning methods are sometimes used to dissolve stubborn residues, particularly when flux-containing powders are processed. Typical chemical treatments operate at ambient conditions and target specific contaminants without exposing saggar to additional thermal stress.

However, production data show that repeated chemical exposure can alter near-surface porosity after 20–40 treatments, increasing powder infiltration risk during subsequent cycles. Thermal burn-off, when controlled below reaction thresholds, preserves pore structure more effectively but requires precise temperature management.

Accordingly, selecting between chemical and thermal cleaning depends on contamination type, frequency, and acceptable lifetime tradeoffs.

Lifetime Impact of Repeated Cleaning Cycles

Each cleaning cycle contributes incremental stress to Alumina Saggar, whether through mechanical abrasion, thermal expansion, or chemical interaction. In long-term operations, saggar subjected to combined cleaning and thermal cycling often reaches end-of-life after 250–400 total cycles, even if thermal exposure alone would allow longer use.

Operators frequently note that saggar failing during cleaning exhibits microcracks aligned with previous contamination zones, indicating cumulative damage rather than isolated incidents. This observation reinforces the need to integrate cleaning frequency into overall lifecycle planning.

Thus, regeneration practices must be treated as part of the operational load profile rather than a maintenance afterthought.

Summary Table: Cleaning and Regeneration Effects on Alumina Saggar

| Cleaning Method | Typical Frequency | Structural Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Light Mechanical Removal | Every 5–10 cycles | Minimal surface damage |

| Thermal Burn-Off (≤900 °C) | Every 20–30 cycles | Preserves pore structure |

| Chemical Cleaning | Every 10–20 cycles | Alters near-surface porosity |

| Surface Roughness Increase (%) | 15 – 25 | Accelerates powder adhesion |

| Total Service Life (cycles) | 250 – 400 | Depends on cleaning strategy |

Moreover, once cleaning and regeneration practices are understood, material selection inevitably becomes a comparative exercise, because powder-based manufacturers routinely evaluate Alumina Trays against alternative saggar materials when stability or lifetime targets are not met.

Performance Comparison with Alternative Saggar Materials

Material comparison is unavoidable in powder-based thermal manufacturing, since each saggar material introduces distinct tradeoffs between thermal stability, contamination risk, and operational cost. Furthermore, perceived upgrades often solve one limitation while introducing another. Consequently, a balanced comparison clarifies where Alumina Saggar remains optimal and where alternatives become necessary.

Alumina Versus Silicon Carbide in Powder Systems

Silicon carbide saggar is frequently considered when thermal shock resistance and high thermal conductivity are prioritized. With thermal conductivity values exceeding 100 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹, SiC transfers heat rapidly, reducing internal temperature gradients within powder beds.

In practice, powder lines using SiC saggar often achieve faster ramp rates, yet operators report increased risk of chemical interaction when processing oxide powders containing alkali or volatile species. After 60–120 cycles, surface reactions can generate secondary phases that contaminate powder batches. By contrast, Alumina Saggar maintains chemical inertness but exhibits lower thermal conductivity, typically 20–30 W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹, which moderates heat flow.

Therefore, SiC favors thermal responsiveness, while alumina prioritizes chemical stability and predictable powder chemistry.

Alumina Versus Mullite Based Saggar Solutions

Mullite-based saggar offers lower thermal expansion, commonly around 5.0 ×10⁻⁶ /K, which improves thermal shock tolerance under rapid cycling. This characteristic makes mullite attractive for mid-temperature powder processing below 1,300 °C.

However, industrial feedback indicates that mullite saggar experiences accelerated creep deformation above 1,350 °C, with noticeable warping after 100–180 cycles under moderate powder loads. Alumina Saggar, although less shock tolerant, sustains shape integrity over longer dwell times at higher temperatures when geometry is properly designed.

Accordingly, mullite suits moderate thermal regimes, whereas alumina remains preferable for extended high-temperature powder operations.

Selection Tradeoffs Across Cost Stability and Risk

Selecting saggar material requires weighing short-term performance gains against long-term process risk. While alternative materials may reduce specific failure modes, they often introduce new variables such as contamination pathways, deformation mechanisms, or cleaning limitations.

Production teams frequently recount trials where alternative saggar materials reduced cracking incidence by 30–40% yet increased powder rejection rates due to chemical interaction. In contrast, Alumina Saggar typically delivers lower variability across batches, even if its absolute cycle life is modestly lower under aggressive thermal shock conditions.

Thus, material selection should be framed as a risk management decision rather than a simple performance upgrade.

Summary Table: Comparative Performance of Common Saggar Materials

| Material Type | Thermal Conductivity (W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹) | Thermal Expansion (×10⁻⁶ /K) | Typical Cycle Life (cycles) | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alumina Saggar | 20 – 30 | 7.5 – 8.2 | 250 – 450 | Thermal shock sensitivity |

| Silicon Carbide Saggar | >100 | 4.0 – 4.5 | 150 – 300 | Chemical interaction risk |

| Mullite Saggar | 5 – 7 | ~5.0 | 100 – 180 | High-temperature creep |

| Cordierite Mullite | 2 – 4 | ~2.5 | 80 – 150 | Limited temperature ceiling |

Additionally, after material comparisons clarify relative tradeoffs, effective implementation still depends on how clearly Alumina Trays are specified, because ambiguous requirements often lead to premature failure even when the material choice is appropriate.

Specification Parameters Commonly Required by Powder Manufacturers

Alumina Saggar specifications translate process intent into measurable engineering constraints that suppliers can reliably reproduce. Moreover, powder-based manufacturers increasingly formalize these parameters to reduce variability across batches and production sites. Consequently, clear specification parameters function as both a quality safeguard and a communication bridge between engineering and procurement teams.

Dimensional Tolerances and Flatness Expectations

Dimensional accuracy governs how Alumina Saggar integrates with automated handling systems and furnace fixtures. In powder production lines, typical dimensional tolerances range from ±0.5 to ±1.5 mm for overall length and width, while flatness requirements on the saggar base commonly fall within 0.3–0.8 mm across the working surface.

In practice, engineers frequently observe that saggar exceeding 1.0 mm flatness deviation introduces uneven powder bed thickness, which later manifests as nonuniform thermal exposure. During one commissioning phase, operators reported that tightening flatness control from 1.2 mm to 0.5 mm reduced batch-to-batch powder variation by approximately 18%, without altering furnace parameters.

Therefore, dimensional and flatness tolerances are not cosmetic details but direct contributors to powder consistency and handling reliability.

Density Purity and Surface Condition Metrics

Material density and surface condition define how Alumina Saggar interacts with fine powders over repeated cycles. Typical specifications call for bulk density above 3.7 g/cm³ and open porosity below 5%, particularly when powders contain particles smaller than 10 µm.

In industrial environments, saggar surfaces with average roughness values exceeding Ra 6–8 µm tend to accumulate powder residues after 70–100 cycles, even when cleaning routines are applied. Conversely, smoother surfaces delay adhesion onset and reduce infiltration risk, extending effective service life by 20–30% based on internal maintenance records.

Thus, density and surface metrics form a preventive barrier against contamination and premature degradation.

Thermal Limits and Operating Envelopes

Thermal limits define the safe operating envelope of Alumina Saggar across peak temperature, dwell duration, and ramp rate. Common specifications identify continuous operating temperatures of 1,400–1,600 °C, with maximum ramp rates between 3–6 °C/min, depending on geometry and load.

Field experience shows that exceeding specified ramp rates by even 1–2 °C/min accelerates crack initiation, reducing average saggar lifespan by 25–35%. Production engineers often recall early trials where aggressive ramp schedules improved throughput but led to frequent saggar replacement within 150 cycles, negating productivity gains.

Accordingly, thermal specifications must align with both material capability and operational discipline.

Summary Table: Typical Specification Parameters for Alumina Saggar in Powder Manufacturing

| Specification Category | Common Range | Process Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Dimensional Tolerance (mm) | ±0.5 – ±1.5 | Ensures handling compatibility |

| Base Flatness (mm) | 0.3 – 0.8 | Stabilizes powder bed thickness |

| Bulk Density (g/cm³) | ≥3.7 | Limits powder infiltration |

| Open Porosity (%) | ≤5 | Reduces contamination risk |

| Surface Roughness Ra (µm) | ≤6 – 8 | Delays powder adhesion |

| Continuous Temperature (°C) | 1,400 – 1,600 | Defines safe thermal envelope |

| Ramp Rate (°C/min) | 3 – 6 | Controls thermal fatigue |

Moreover, once specification parameters are clearly established, decision-making naturally shifts toward evaluating Alumina Trays through a lifecycle cost lens, because short-term purchasing savings often conceal long-term operational losses in powder-based thermal manufacturing.

Lifecycle Cost Perspective in Powder Production

Lifecycle cost analysis reframes Alumina Saggar from a consumable item into a process asset whose value unfolds over time. Furthermore, powder-based production environments magnify indirect costs such as downtime, batch instability, and maintenance labor. Consequently, understanding lifecycle cost enables manufacturers to balance durability, predictability, and operational continuity rather than focusing solely on unit price.

Cost Per Cycle Versus Unit Purchase Price

Cost per cycle provides a more accurate performance metric than upfront purchase price. In powder manufacturing lines, Alumina Saggar unit prices may vary modestly, yet service life often ranges from 200 to over 450 cycles, depending on design and operating discipline.

Production teams frequently observe that saggar with 25–30% higher unit cost delivers 40–60% more usable cycles, resulting in a lower effective cost per cycle. During commissioning reviews, engineers often calculate that reducing replacement frequency by even one change per month stabilizes production schedules and reduces handling-induced defects.

Therefore, cost per cycle aligns procurement decisions with actual process economics rather than short-term budget constraints.

Downtime Risk and Batch Loss Exposure

Unplanned saggar failure introduces cascading operational risks beyond replacement costs. In powder-based thermal manufacturing, a single saggar fracture can disrupt an entire furnace load, affecting 20–80 kg of powder, depending on batch configuration.

Operators frequently report that saggar-related incidents trigger 4–12 hours of downtime for cooling, debris removal, and system inspection. Even when no powder is scrapped, delayed processing introduces scheduling ripple effects that persist across subsequent shifts. Over extended periods, such disruptions reduce effective furnace utilization by 5–10%, based on internal operational metrics.

As a result, saggar reliability directly influences throughput stability and risk exposure across powder lines.

Replacement Planning and Inventory Strategy

Proactive replacement planning mitigates the impact of saggar degradation before critical failure occurs. In mature powder operations, saggar replacement thresholds are often set when flatness deviation exceeds 0.6–0.8 mm or when microcrack density visibly increases after 250–300 cycles.

Experienced planners integrate saggar lifecycle data into inventory models, maintaining safety stock equivalent to 1.2–1.5× monthly consumption. This approach reduces emergency procurement events and allows controlled phase-out of aging saggar without interrupting production flow.

Thus, structured replacement planning transforms saggar management into a predictable, low-risk operational routine.

Summary Table: Lifecycle Cost Factors Associated with Alumina Saggar

| Lifecycle Factor | Typical Range | Operational Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Service Life (cycles) | 200 – 450+ | Determines replacement frequency |

| Unit Cost Increase (%) | 25 – 30 | Often offsets higher cycle yield |

| Cost per Cycle Reduction (%) | 20 – 40 | Improves long-term economics |

| Downtime per Failure (hours) | 4 – 12 | Impacts throughput continuity |

| Furnace Utilization Loss (%) | 5 – 10 | Reflects indirect cost burden |

| Safety Stock Multiplier | 1.2 – 1.5× | Stabilizes supply planning |

Furthermore, after lifecycle cost considerations are clarified, real-world deployment inevitably reveals recurring failure patterns that appear across powder-based production lines regardless of material grade or supplier.

Typical Failure Scenarios Observed in Powder Lines

Alumina Saggar failures in powder-based thermal manufacturing rarely occur randomly. Instead, they follow recognizable scenarios shaped by thermal history, loading practice, and cumulative handling effects. Understanding these scenarios helps engineers distinguish between correctable process issues and unavoidable end-of-life behavior.

-

Progressive bottom warping under sustained powder load

In many powder lines, saggar bottoms gradually lose flatness after extended exposure above 1,300 °C. Operators often notice this deformation only when powder beds begin to show uneven thickness. Over time, warping exceeding 0.7 mm alters heat distribution and accelerates downstream quality variation.

Consequently, this failure mode reflects creep accumulation rather than sudden overload. -

Edge cracking initiated at thickness transitions

Cracks frequently originate at junctions between walls and base where thickness changes abruptly. Field inspections indicate that more than 60% of visible cracks appear along these transitions after 200–300 cycles. Once initiated, cracks propagate slowly until a critical length is reached.

Therefore, geometry design and inspection frequency strongly influence detection timing. -

Surface glazing and residue build-up from reactive powders

Powders containing fluxing additives can form thin vitrified layers on saggar surfaces after 80–120 cycles. These layers increase surface roughness and promote further adhesion. Operators often misinterpret glazing as harmless discoloration until cleaning becomes ineffective.

As a result, surface reactions gradually convert saggar into a contamination source. -

Handling-induced chipping in automated transfer systems

In automated lines, repeated contact with grippers or rails causes localized chipping along edges and notches. Damage rates rise noticeably after 800–1,000 handling cycles, even when thermal performance remains acceptable.

Accordingly, mechanical wear becomes a limiting factor independent of thermal fatigue.

Taken together, these scenarios demonstrate that most saggar failures emerge from cumulative mechanisms rather than isolated mistakes, allowing preventive strategies when patterns are recognized early.

Summary Table: Common Failure Scenarios in Powder-Based Alumina Saggar Use

| Failure Scenario | Typical Onset (cycles) | Primary Trigger |

|---|---|---|

| Bottom Warping | 200 – 300 | High-temperature creep |

| Edge Cracking | 200 – 350 | Thermal stress concentration |

| Surface Glazing | 80 – 120 | Powder–surface reaction |

| Residue Hardening | 100 – 150 | Repeated partial sintering |

| Handling Chipping | 800 – 1,000 handling events | Mechanical impact |

Additionally, recognizing recurring failure scenarios makes it easier to identify misapplications, where Alumina Trays are used outside their effective operating envelope despite meeting nominal specifications.

Common Misapplications of Alumina Saggar

Misapplication of Alumina Saggar in powder-based thermal manufacturing often arises from implicit assumptions rather than explicit design errors. Moreover, these misuses typically remain unnoticed during early production stages and only surface after repeated cycles. Consequently, understanding common misapplications helps prevent avoidable degradation and process instability.

-

Using standard saggar geometry for high powder load density

Standard saggar designs are sometimes deployed in applications where powder load density exceeds 5–6 kg per unit, despite being optimized for lighter loads. Over extended dwell times above 1,300 °C, this mismatch accelerates creep deformation and bottom warping.

Therefore, load-specific geometry must be considered whenever powder mass increases. -

Applying aggressive thermal ramp rates to thick-walled saggar

Thick-walled Alumina Saggar is occasionally selected for perceived durability, then subjected to ramp rates exceeding 6 °C/min. This combination creates steep internal thermal gradients, leading to edge cracking after 100–150 cycles.

As a result, thickness alone does not guarantee robustness without corresponding ramp control. -

Reusing saggar beyond functional flatness limits

Production teams sometimes continue using saggar with flatness deviation beyond 0.8–1.0 mm, assuming no immediate fracture risk. However, uneven powder beds introduced by distorted saggar increase batch variability and downstream rework rates.

Accordingly, functional geometry thresholds should define end-of-life rather than visible damage alone. -

Cleaning chemically reactive residues with incompatible methods

Reactive powder residues are occasionally removed using chemical agents that alter alumina surface chemistry. After 20–30 cleaning cycles, near-surface porosity increases, accelerating subsequent powder infiltration.

Thus, cleaning compatibility must be validated alongside powder chemistry.

These misapplications highlight that Alumina Saggar reliability depends as much on correct usage alignment as on material quality itself.

Summary Table: Frequent Misapplications and Resulting Risks

| Misapplication Type | Typical Condition | Resulting Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Powder Load | >5–6 kg per saggar | Accelerated creep deformation |

| High Ramp Rate with Thick Walls | >6 °C/min | Edge cracking |

| Extended Use Beyond Flatness Limit | >0.8–1.0 mm deviation | Powder inconsistency |

| Incompatible Cleaning Methods | >20–30 cycles | Increased infiltration |

| Geometry–Process Mismatch | Non-optimized design | Early failure |

Moreover, once misapplications are identified and corrected, sustained performance improvement depends on collaborative engineering, where Alumina Trays are designed, validated, and refined in alignment with real powder process conditions.

Engineering Collaboration in Custom Alumina Saggar Development

Custom Alumina Saggar development becomes effective only when material design, structural geometry, and powder process data are integrated into a single engineering workflow. Furthermore, powder-based manufacturing imposes constraints that cannot be resolved through catalog specifications alone. Consequently, collaborative engineering aligns saggar design with actual thermal profiles, loading behavior, and lifecycle targets.

Translating Powder Process Data into Saggar Design

Effective customization begins with translating powder process parameters into structural and material requirements. Typical inputs include peak temperature, ramp rate, dwell duration, powder mass distribution, and handling frequency, which collectively define the stress environment experienced by the saggar.

In practice, engineers often discover that adjusting wall thickness by 1–2 mm or increasing internal corner radii by 2–3 mm extends service life by 20–35% under identical thermal schedules. During one powder line upgrade, incorporating asymmetric reinforcement in high-load zones reduced bottom deformation from 0.9 mm to below 0.4 mm after 250 cycles.

Therefore, data-driven geometry adaptation converts empirical trial-and-error into predictable performance outcomes.

Prototyping Validation and Iteration Loops

Prototype validation bridges the gap between design intent and production reality. Initial prototypes are typically evaluated over 50–100 thermal cycles, focusing on flatness retention, crack initiation, and residue behavior rather than ultimate failure.

Experienced teams report that two to three controlled iteration loops are sufficient to converge on a stable saggar design, reducing later production failures by 40–60%. Operators often recall early validation phases where minor geometric revisions eliminated recurrent edge cracking without altering furnace operation.

Thus, structured prototyping shortens time-to-stability and minimizes disruptive redesigns during mass production.

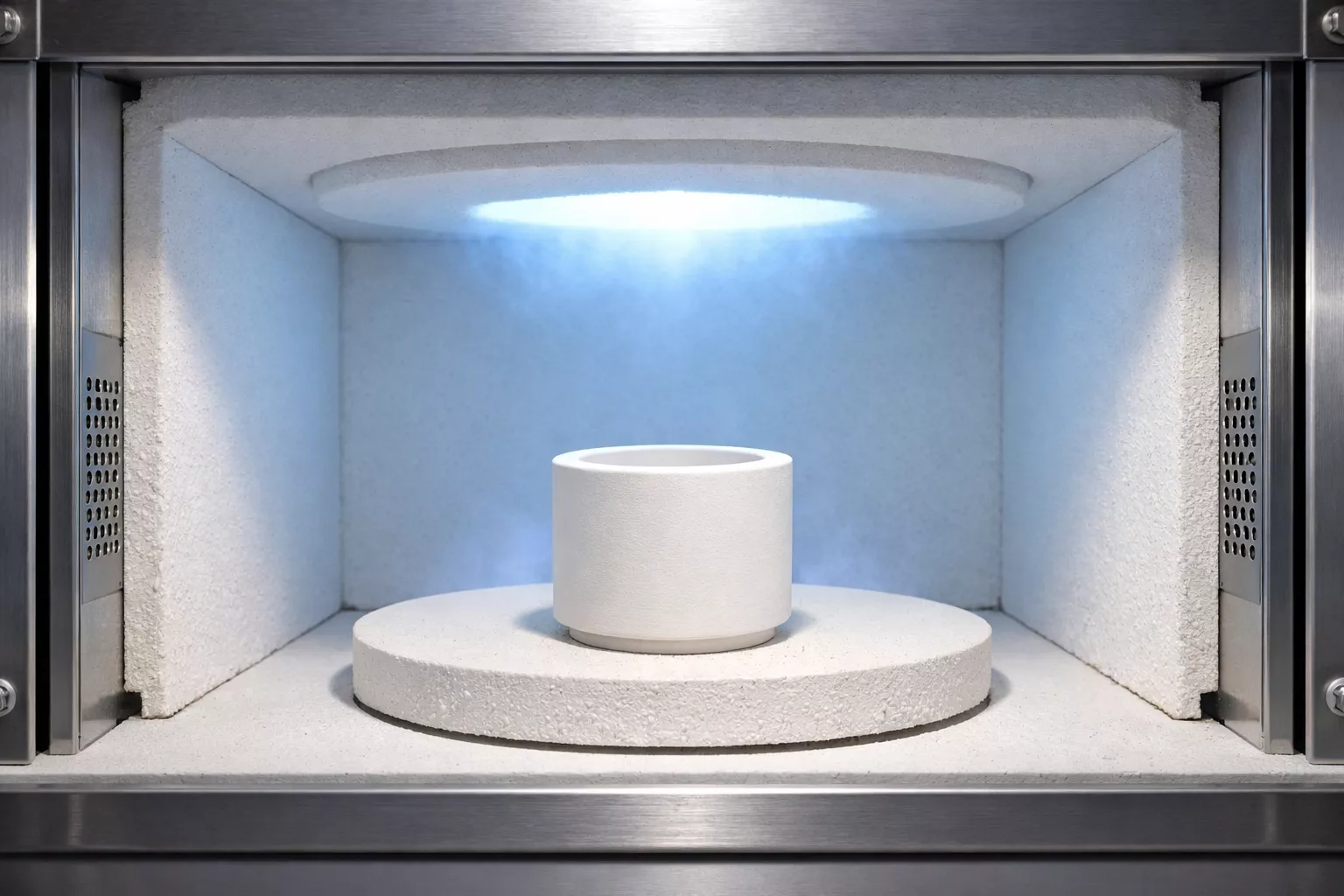

ADCERAX One Stop Manufacturing and Quality Control

ADCERAX integrates material preparation, forming, sintering, machining, and inspection into a unified manufacturing flow for Alumina Saggar. This approach enables consistent translation of engineering intent into repeatable production outcomes.

By maintaining dimensional inspection thresholds within ±0.5 mm and surface condition controls aligned with powder sensitivity, ADCERAX supports both small-batch prototyping and scaled production. Moreover, coordinated quality checkpoints reduce variability across production lots, ensuring that validated designs remain stable over extended supply cycles.

Accordingly, one-stop manufacturing consolidates engineering accountability and accelerates deployment in powder-based thermal manufacturing.

Summary Table: Engineering Collaboration Elements in Custom Alumina Saggar Development

| Collaboration Element | Typical Scope | Performance Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Process Data Integration | Temperature, load, ramp profiles | Aligns design with real stress |

| Geometry Optimization | 1–3 mm design adjustments | 20–35% life extension |

| Prototype Validation Cycles | 50 – 100 | Early failure detection |

| Iteration Loops | 2 – 3 | 40–60% failure reduction |

| Dimensional Control (mm) | ±0.5 | Maintains design fidelity |

| Integrated Manufacturing | One-stop production | Supply consistency |

Furthermore, after engineering collaboration establishes a stable custom solution, supplier selection becomes the final variable shaping long-term reliability, responsiveness, and continuity in powder-based thermal manufacturing.

Practical Guidance for Selecting Alumina Saggar Suppliers

Selecting an Alumina Saggar supplier requires evaluating more than quoted specifications, because supplier capability directly influences how consistently engineered designs are reproduced over time. Moreover, powder-based manufacturing environments magnify small variations in forming, sintering, and inspection discipline. Consequently, supplier selection should focus on engineering alignment and process control rather than transactional convenience.

-

Assess engineering communication depth and responsiveness

Suppliers capable of discussing ramp rates, powder loads, and deformation mechanisms tend to deliver more stable saggar outcomes. In contrast, vendors limited to catalog dimensions often struggle to address process-specific deviations during production scaling.

Therefore, engineering dialogue quality serves as an early indicator of long-term collaboration success. -

Verify forming and sintering process consistency

Powder manufacturers report that saggar from suppliers with controlled forming pressure and sintering profiles shows 15–25% lower dimensional scatter across batches. Consistency at this stage reduces the need for repeated validation and corrective action.

As a result, internal process control matters as much as material selection. -

Evaluate inspection standards and traceability

Suppliers applying routine flatness, density, and surface checks catch deviations before shipment. Field experience suggests that inspection-driven rejection rates below 3% correlate strongly with stable in-line performance.

Accordingly, inspection capability protects downstream production continuity. -

Confirm capacity for iterative improvement

Powder processes evolve over time, and saggar requirements often change with new powders or throughput targets. Suppliers willing to support iterative refinement enable smoother transitions without restarting qualification cycles.

Thus, adaptability becomes a strategic selection criterion rather than a secondary benefit.

Summary Table: Supplier Selection Factors Affecting Alumina Saggar Reliability

| Supplier Factor | Practical Indicator | Manufacturing Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Engineering Communication | Process-level discussion | Faster problem resolution |

| Forming and Sintering Control | Low batch variability | Stable saggar geometry |

| Inspection Discipline | <3% rejection rate | Reduced in-line disruptions |

| Customization Capability | Iterative support | Extended design relevance |

| Production Scalability | Small to large batches | Supply continuity |

Conclusion

Alumina Saggar performance in powder-based thermal manufacturing emerges from aligned material design, geometry control, process discipline, and collaborative engineering rather than isolated specification choices.

ADCERAX supports customized Alumina Saggar development with integrated engineering, controlled manufacturing, and responsive iteration tailored to powder-based thermal manufacturing requirements.

FAQ

How many cycles should Alumina Saggar typically achieve in powder-based processes?

Well-designed saggar commonly operates for 250–450 cycles, depending on powder load, geometry, and thermal profile.

Does higher alumina purity always improve performance?

Higher purity improves chemical stability, but geometry and loading alignment are equally critical for lifecycle reliability.

When should saggar be replaced if no cracks are visible?

Replacement is recommended when flatness deviation exceeds 0.6–0.8 mm, even without visible cracking.

Can one saggar design serve multiple powder systems?

In some cases, yes; however, powders with different particle sizes or additives often require tailored saggar designs to maintain stability.

References: