Alumina crucibles that are not cleaned correctly lose accuracy, waste furnace time, and fail years earlier than they should.

Proper cleaning of alumina crucibles maintains high-temperature performance, reduces contamination carryover, and stabilizes experimental results over hundreds of cycles. This guide explains practical methods, safety rules, and decision thresholds based on real industrial and laboratory practice so that users can extend crucible life instead of replacing it prematurely.

In the following sections, alumina crucibles are treated as engineered tools rather than disposable consumables, and each method is linked to contamination type, temperature history, and risk level so that users can choose procedures that fit their own furnace, chemistry, and workload.

Before understanding individual steps, it is important to see why cleaning alumina crucibles is not just a hygiene task but a core part of thermal process control and data quality management.

Why Proper Cleaning of Alumina Crucibles Matters

Clean alumina crucibles support reproducible analyses, lower scrap rates, and protect furnaces from unintended reactions during repeated thermal cycles.

Properly cleaned alumina crucibles keep the thermal environment stable, reduce unexpected reactions, and prevent trace impurities from accumulating with each firing. Moreover, when deposits are removed in time, microcracks grow more slowly and the crucible survives more heat cycles before catastrophic failure. Consequently, cleaning strategy becomes a lever for quality, safety, and total cost rather than a minor housekeeping detail.

Impact on Measurement Accuracy and Experimental Repeatability

Accurate results depend on alumina crucibles that contribute almost no unknown contamination to the sample. When organics, metal oxides, or flux residues remain inside the bowl, they interact with new batches during firing, and this gradually shifts measured mass or composition. Furthermore, even a residual layer of just 10–20 micrometers can change local atmosphere and wetting behavior, so titration or ash content results start to drift between runs.

In analytical workflows, a relative error1 shift of 1–2% caused by dirty alumina crucibles quickly becomes unacceptable. For instance, in battery cathode R&D where lithium content must be controlled within ±0.3%, such drift can hide genuine formulation effects. Therefore, a clean crucible surface is treated as part of the instrument calibration chain rather than a secondary accessory.

Over time, users who log their results notice that variability shrinks significantly once a strict cleaning protocol is implemented. As a consequence, fewer repeats are required to confirm each data point, furnace time is freed, and statistical confidence improves without investing in new instruments.

Effect on Crucible Structural Integrity and Thermal Shock Performance

Contamination also damages the body of alumina crucibles. When flux or glassy slags freeze on the inner wall, they contract differently from the ceramic during cooling, and this introduces tensile stresses that propagate microcracks. Additionally, metal droplets that infiltrate micro-pores can oxidize on repeated heating, and this expansion accelerates grain boundary degradation.

After dozens of harsh cycles, crucibles that are rarely cleaned show a measurable drop in residual strength. For example, internal testing in many labs finds that flexural strength after 100 cycles can fall by more than 25% when thick flux residues are left in place, whereas cleaned alumina crucibles may retain over 85% of their initial strength at the same cycle count. Thus, appearance is not the only reason to keep surfaces clean.

As cracks grow, thermal shock resistance also declines. Consequently, a crucible that once tolerated a 300°C temperature step without failure may start cracking at only 180–200°C. In production environments using fast furnace ramps, this loss of safety margin increases the chance of an unexpected break and associated furnace contamination.

Cost, Downtime, and Inventory Implications

From a cost perspective, cleaning alumina crucibles is far cheaper than replacing them frequently. If a crucible rated for 500 cycles fails after 150 cycles due to poor cleaning, then more than two-thirds of its potential service life has been wasted. Moreover, emergency replacement often forces users to purchase small quantities at premium prices or to interrupt campaigns while waiting for new stock.

Downtime is equally important. When a crucible fails mid-run, the furnace may need 4–8 hours for cool-down, cleaning, and reheating. In continuous operations such as catalyst calcination or ash determination lines, this interruption can delay shipment schedules and consume electricity that produces no saleable output. Therefore, many plants track mean time between crucible failures as a performance metric.

In addition, poor cleaning forces sites to hold more spare alumina crucibles to hedge against unexpected breakage. By contrast, a robust cleaning regime that doubles average life can allow inventory levels to drop by 30–40% while maintaining the same risk profile.

Summary of Cleaning Benefits in Quantitative Terms

| Aspect | Typical issue if crucible is dirty | Improvement with proper cleaning (%) | Example environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass measurement repeatability | Drift of 1.5–2.0% over 30 runs | Variability reduced by 50–70% | Analytical laboratory furnace |

| Mean crucible life (cycles) | Breakage after 150–200 cycles | Life extended to 350–450 cycles | Materials R&D sintering lab |

| Emergency downtime (hours/month) | 6–10 hours of unplanned stoppage | Cut to 2–4 hours | Pilot production line |

| Spare crucible inventory | Safety stock at 120% of monthly use | Reduced to 70–80% of monthly use | Industrial calcination workshop |

Before choosing a cleaning procedure, users must identify which contamination is actually present on their alumina crucibles instead of relying on visual impression alone.

Identify the Contamination Type Before Cleaning

Identifying what is stuck on alumina crucibles helps avoid over-aggressive methods that shorten life or the wrong chemicals that create new residues.

Correct identification of contamination on alumina crucibles guides users toward the least aggressive method that still works reliably. Furthermore, classification by residue type allows cleaning workflows to be standardized, which reduces trial-and-error and lowers the risk of incompatible chemicals or temperatures. As a result, contamination diagnosis becomes the first formal step before any heat or acid treatment.

Organic and Carbonaceous Residues

Organic residues derive from binders, oils, polymers, and incomplete combustion of powders. When alumina crucibles are used for organic ash tests2, they often show brown to black films or patchy soot-like areas along the inner wall. Additionally, these deposits usually soften or char around 400–600°C and burn away if enough oxygen and dwell time are provided.

In practice, surfaces covered mainly by organics still feel relatively smooth when touched with a clean ceramic rod. For example, a crucible used for polymer burnout may show a thin matte film but no hard glassy spots, and this indicates that thermal cleaning in air is the primary remedy. Typically, such stains can be removed in 1–2 furnace cycles without any chemical treatment.

Because organic deposits release gases during burnout, insufficient pre-cleaning can cause local overpressure and spalling of delicate sintered parts placed above the crucible in the same furnace.

Metal and Oxide Deposits

Metallic and oxide residues form when alumina crucibles are used for alloy melting, slag testing, or oxide synthesis. These residues often appear as dull grey, green, or rust-colored patches that bond strongly to the ceramic. Moreover, their melting points are usually higher than the previous process temperature, so simple reheating does not detach them.

When a crucible interior shows distinct colored islands, sometimes with a metallic sheen or rough crystallized surfaces, the contamination is likely dominated by oxides or intermetallic phases. For instance, iron-rich slags can leave reddish-brown layers, whereas copper-containing melts may result in dark green or black-green adherent areas. Therefore, targeted chemical dissolution using acids or alkalis becomes necessary.

If such deposits exceed a thickness of about 0.3–0.5 mm, they also act as local stress raisers that accelerate crack initiation during repeated heating and cooling.

Glassy Flux and Slag Residues

Fluxes and glassy slags produce shiny, vitreous films or pools on alumina crucibles. These residues are usually translucent to opaque, with colors ranging from colorless to green or amber depending on composition. Additionally, their thermal expansion often differs significantly from that of alumina, so they tend to craze or chip under thermal cycling.

In many laboratories, crucibles used with borate or phosphate fluxes show a characteristic smooth glass lining near the bottom. Because this layer can have hardness comparable to or exceeding that of the alumina crucibles themselves, mechanical scraping is risky and slow. Consequently, controlled chemical attack with suitable reagents, combined with partial mechanical assistance, is preferred.

When glassy layers cover more than 30–40% of the internal surface, they should be evaluated critically, since the remaining clean alumina area for future reactions becomes too small for reliable results.

Contamination Types and Preferred Cleaning Approaches

| Contamination type | Typical visual cues | Dominant risk to alumina crucibles | Primary cleaning method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic / carbonaceous | Brown to black matte films, soot-like patches | Gas evolution, incomplete burnout | Thermal cleaning in air |

| Metal / metal oxides | Colored rough islands, metallic or dull sheen | Chemical reaction with Al2O3 | Chemical cleaning with acids |

| Glassy flux / slags | Smooth shiny layers, vitreous pools | Differential expansion, cracking | Chemical plus gentle mechanical |

Once residue type is known, the next step is to ensure that cleaning does not create new hazards for personnel or damage the alumina crucibles through unsafe handling.

Safety Principles Before Cleaning Alumina Crucibles

Safety rules for cleaning alumina crucibles focus on hot-surface hazards, corrosive chemicals, and fine particulate dust generated during brushing.

Safe cleaning of alumina crucibles combines standard laboratory PPE with procedures tailored to hot ceramics and corrosive reagents. Furthermore, because many cleaning steps involve reheating, soaking, or brushing dry residues, protection against thermal burns and inhalation of fine particles is essential. Therefore, a brief safety review before each cleaning session prevents small mistakes from escalating into injuries.

Personal Protective Equipment and Workspace Setup

Before starting, users should wear chemical-resistant gloves, splash goggles, and a lab coat whose sleeves fully cover the wrists. Additionally, when brushing dry residues from alumina crucibles, a particulate mask rated at least FFP2 or N953 is recommended in order to keep airborne dust exposure below typical occupational limits. As crucibles may still retain hidden hot spots, heat-resistant gloves should be kept within reach.

The workspace should provide a stable surface that resists heat and chemical attack. For example, many labs place a ceramic tile or refractory board under alumina crucibles during cleaning so that accidental spills or drops do not damage the bench. Moreover, a local exhaust hood or downdraft table helps capture dust and fumes from acids, especially when treating multiple crucibles in one batch.

Because repeated cleaning sessions can create a false sense of routine, some facilities keep a short printed checklist near the sink or furnace to confirm PPE and ventilation are in place before work begins.

Hot Surface, Thermal Shock, and Handling Hazards

Alumina crucibles may look cool long before they reach safe handling temperatures. For instance, a crucible removed from an 800°C furnace can still measure more than 250°C at the rim after 15 minutes in still air. Consequently, all crucibles should be treated as hot unless their temperature has been verified with an infrared thermometer or they have rested for a defined time on a heat-safe surface.

Rapid quenching of hot alumina crucibles in water is rarely acceptable. Even when thermal shock resistance is advertised as good, plunging from 900°C to room temperature can cause internal microcracking that only becomes visible after several more cycles. Therefore, cool-down stages should be planned, such as lowering temperature at 3–5°C per minute or transferring hot crucibles to a ventilated refractory shelf.

Using dedicated tongs sized for the crucible geometry further reduces the risk of dropping or squeezing the crucible, which otherwise could result in chipped rims and shortened service life.

Chemical Handling and Waste Management

Chemical cleaning of alumina crucibles often uses acids such as nitric or hydrochloric, or occasionally alkaline solutions to attack silicate residues. Consequently, splash risks are significant, especially when handling volumes of 500–2000 ml for industrial-sized crucibles. Acids should always be poured slowly along the inner wall of the beaker or container to avoid sudden boiling or splashing caused by exothermic reactions.

Spent solutions must be collected in labeled waste containers rather than poured directly into drains. For example, metal-rich acid used after cleaning crucibles from alloy melting can contain tens to hundreds of milligrams per liter of nickel, chromium, or copper, and this requires treatment by a licensed waste handler. Moreover, neutralization reactions can release heat or gas, so they should be done in small increments under a fume hood.

Clear labeling that links each waste bottle to “alumina crucibles cleaning” helps future audits and demonstrates that ceramic-maintenance activities are properly controlled.

Proper handling and safety preparation create the foundation for every cleaning workflow, and the following alumina crucible cleaning methods ensure reliable performance across diverse contamination scenarios.

Cleaning Methods for Alumina Crucibles

Cleaning methods for alumina crucibles must be selected according to the chemical nature, thickness, and bonding strength of the residues formed during high-temperature use. Moreover, each method offers distinct advantages that address organic films, metallic deposits, or glassy flux layers with different levels of aggression and precision. Consequently, understanding these method categories ensures that subsequent cleaning actions remain controlled, reproducible, and compatible with the crucible’s structural integrity.

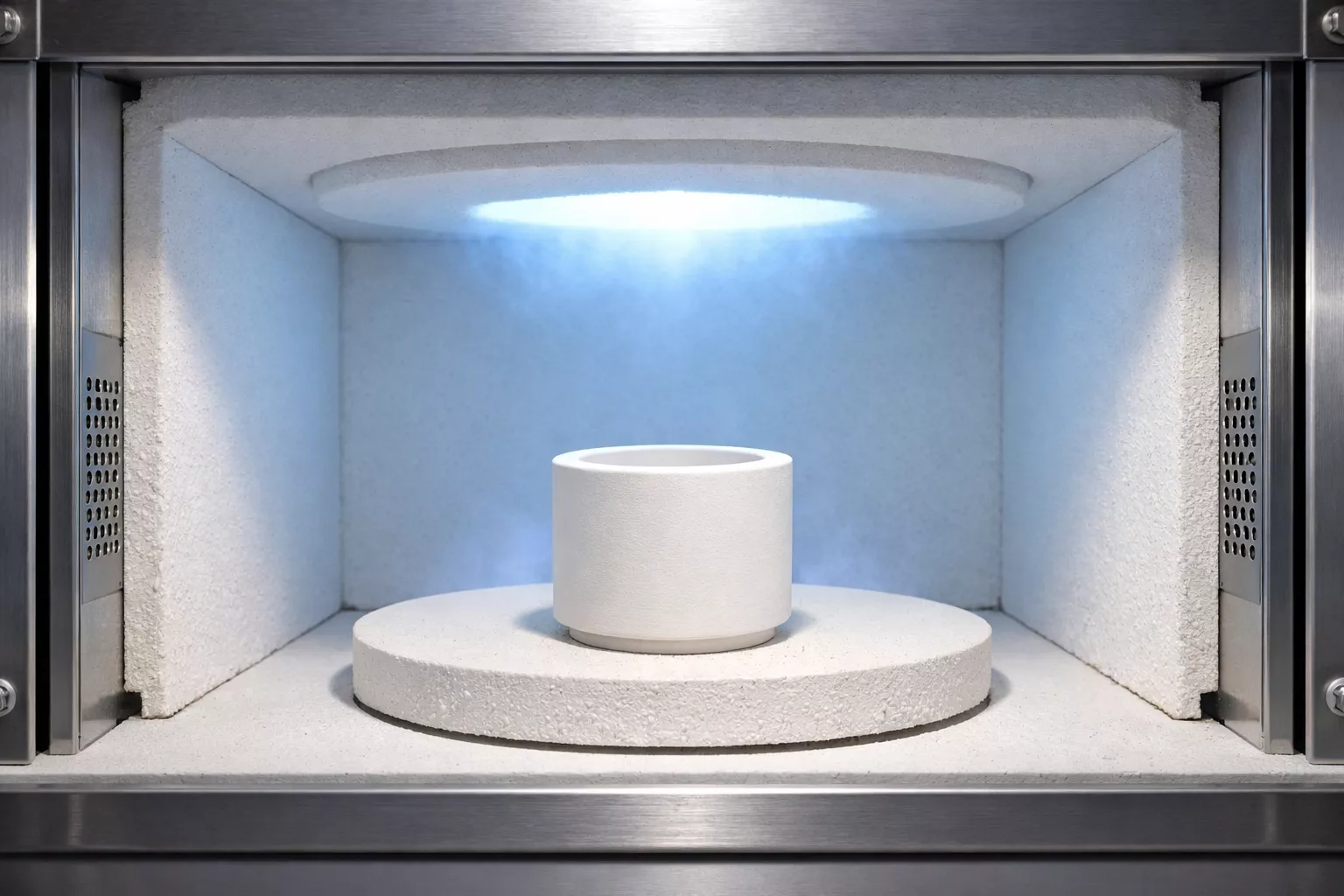

Method 1: Thermal Cleaning (Recommended for Organic Residues)

For alumina crucibles loaded mainly with organics or light carbon, thermal cleaning in air often restores a clean surface with minimal additional risk.

Thermal cleaning leverages the high temperature capability of alumina crucibles to oxidize organics directly in the furnace, thereby avoiding chemical waste. Additionally, when furnace ramps and dwell times are controlled, this method removes residues while keeping thermal gradients low enough to preserve crucible strength. As a result, many laboratories adopt thermal cleaning as their default first step before considering acids or mechanical methods.

When Thermal Cleaning Is Appropriate

Thermal cleaning works best when visual inspection shows thin films or soot without thick glassy or metallic layers. If a stainless-steel spatula or ceramic probe glides smoothly over the surface and leaves mainly dark smears, the residue is probably combustible carbon rather than hard slag. In that case, heating the alumina crucibles under air or slightly oxygen-enriched atmosphere is efficient.

However, if bright metallic islands or glossy vitreous spots are visible, thermal cleaning alone will not be sufficient. In such cases, overheating in an attempt to “burn everything out” can damage the crucible glaze or even react alumina with aggressive slags. Therefore, maximum cleaning temperature is typically limited to 100–150°C above normal operating temperature but still within the rated limit, often around 1000–1100°C for routine work.

As a rule of thumb, thermal cleaning is considered economical if residues are reduced by at least 80% in one or two cycles. Beyond that, additional furnace time brings diminishing returns, and alternative methods should be considered.

Recommended Furnace Ramp and Dwell Parameters

A typical thermal cleaning schedule for alumina crucibles starts with a slow pre-heat to drive off moisture and low-boiling organics. For example, they may be heated from room temperature to 200°C at 2–3°C per minute and held for 30–60 minutes. Afterwards, the ramp can be increased to 5°C per minute up to 600–800°C to oxidize carbonaceous material, with dwell times between 1 and 3 hours depending on load and residue thickness.

During this process, alumina crucibles should be spaced at least 5–10 mm apart to allow circulation of hot air or furnace gases. Moreover, placing them on an alumina setter plate reduces direct contact with furnace shelves and helps distribute mechanical stresses. When the burnout step is complete, controlled cooling at 3–5°C per minute prevents thermal shock and protects crucible integrity.

In many cases, color and smell provide intuitive confirmation: any visible smoke and pungent organic odor should disappear by the end of the soak period, leaving the alumina crucibles pale white or ivory again with only faint discoloration.

Example Thermal Cleaning Schedule for Organic Contamination

| Stage | Temperature range (°C) | Ramp rate (°C/min) | Typical dwell time (min) | Main purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-dry | 25 → 200 | 2–3 | 30–60 | Remove moisture and low-boiling solvents |

| Carbon burnout | 200 → 650 | 3–5 | 60–120 | Oxidize carbonaceous residues |

| High-temperature polish | 650 → 900 | 3–5 | 30–90 | Complete combustion, smooth surface |

| Controlled cool | 900 → 200 | 3–5 | 60–120 | Avoid thermal shock and microcracking |

Case Study: Battery Cathode Lab in South Korea (S. Kim)

S. Kim, Process Manager in the cathode development line of a South Korean battery manufacturer, noticed that gravimetric ash measurements were drifting by roughly 1.2% over a month. Initially, the team suspected balance calibration or powder inhomogeneity; however, visual inspection showed that alumina crucibles had developed uniform dark films after 40–50 cycles of binder burnout.

After reviewing furnace logs, Kim introduced a standardized thermal cleaning run every Friday evening for all alumina crucibles that had handled organic-rich slurries. The schedule used a 2°C per minute ramp to 200°C, then 5°C per minute to 750°C with a 2-hour hold in air. Additionally, crucibles were now spaced on alumina setter plates instead of being stacked in tight clusters.

Within three weeks, control charts showed that measurement drift had fallen below 0.3%, and crucible replacements due to cracking dropped by about 40% over the next quarter. Consequently, management approved this cleaning run as a permanent part of the weekly maintenance plan, and furnace scheduling software was adjusted so that alumina crucibles cleaning no longer conflicted with production firing.

When thermal cleaning cannot remove metal or flux residues, chemical dissolution becomes the next controlled option, provided it is matched carefully to contaminant chemistry.

Method 2: Chemical Cleaning (For Metals, Oxides, Flux Residues)

Chemical cleaning of alumina crucibles targets metal oxides and glassy slags using controlled acid or alkali solutions that selectively attack residues.

Chemical treatment is essential when alumina crucibles carry thick or strongly bonded residues that barely respond to thermal cleaning. Moreover, by choosing appropriate reagents and concentrations, users can dissolve many metallic and silicate phases faster than they would be abraded mechanically. Nevertheless, because aggressive chemistry can also etch alumina, cleaning cycles and solution strengths must be limited and recorded systematically.

Choosing Suitable Acids or Alkalis for Each Residue Type

Different residues respond to different chemistries, so users should classify them before mixing solutions. Many transition metal oxides from Fe, Ni, or Co melts can be removed with moderately strong nitric acid solutions between 10% and 30% by volume. On the other hand, silicate-rich glassy slags often require warm alkali solutions, such as sodium hydroxide near 5–10%, to attack the Si–O network more effectively.

However, hydrofluoric acid is generally avoided for routine alumina crucibles cleaning because it attacks Al2O3 itself and introduces serious safety hazards. Similarly, concentrated caustic solutions at high temperature can roughen the alumina surface and lower its flexural strength by more than 10–15% after only a few cycles. Therefore, users often start with milder reagents and increase exposure time rather than jumping to extreme chemistries.

In all cases, small-scale tests on heavily damaged or sacrificial crucibles are recommended first. If weight loss of the alumina substrate exceeds 0.3–0.5% per cleaning cycle, the procedure should be considered too aggressive for routine use.

Practical Soaking and Rinsing Procedure

A typical workflow begins by placing cooled alumina crucibles into a beaker or polypropylene container large enough that solution covers residues by at least 10–15 mm. Subsequently, the chosen acid or alkali is added slowly to reach a working volume that fills 60–80% of the vessel, leaving room for effervescence. Gentle stirring or occasional swirling improves contact between the solution and stubborn residues.

Soaking times vary from 30 minutes to several hours depending on contamination thickness and temperature; for instance, warm baths at 40–60°C often cut required time by half compared to room temperature. After soaking, crucibles are rinsed thoroughly with deionized water until pH of the rinse remains stable and near neutral. They are then dried at 100–150°C for 1–2 hours before any further heating.

To prevent cross-contamination, users typically separate cleaning baths by residue category, such as “Fe/Ni alloy residues” or “borate flux residues,” and replace solutions once metal concentration or dissolved solids exceed predetermined thresholds.

Example Parameters for Common Chemical Cleaning Scenarios

| Residue type | Typical solution | Temperature (°C) | Soak time range (min) | Notes on alumina crucibles impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron-rich oxides | 20–30% HNO3 in water | 20–40 | 30–120 | Minimal etching when cycles are limited |

| Nickel / cobalt oxides | 15–25% HCl or mixed acids | 20–40 | 45–180 | Monitor for pitting after repeated cycles |

| Borate-based glassy fluxes | 5–10% NaOH aqueous solution | 40–60 | 60–240 | Can roughen surface if overexposed |

| Silicate slags | 5–8% NaOH or KOH | 40–70 | 90–240 | Use plastic tools for mechanical assist |

Case Study: Research Institute in Germany (Dr. Markus H.)

Dr. Markus H., from the Materials Analysis Department at a German research institute, led a project analyzing alloy inclusions using borate flux fusion followed by ICP. Over time, his team observed that alumina crucibles developed persistent greenish glass layers which made complete flux transfer difficult and occasionally contaminated blanks.

Initial attempts at longer thermal cleaning cycles brought only minor improvement and consumed valuable furnace capacity. Therefore, Dr. Markus introduced a dedicated chemical cleaning step using a 7% sodium hydroxide solution at 60°C. Alumina crucibles were soaked for 90 minutes, then lightly brushed with a plastic rod and rinsed thoroughly before being dried at 120°C.

Within two months, flux carryover measurements dropped by nearly 60%, and crucible rejection rates fell from around 18% per quarter to under 7%. Furthermore, microscopic inspection after ten cleaning cycles showed surface roughness increase of less than 0.3 micrometers, which was acceptable for their application. As a consequence, this combined chemical and light mechanical protocol became part of their standard operating procedure for alumina crucibles used in fusion work.

When chemical soaking alone cannot dislodge strongly sintered residues, carefully controlled mechanical assistance can be added without turning alumina crucibles into consumable abrasives.

Method 3: Mechanical-Assisted Cleaning (For Tough Sintered Residues)

Mechanical assistance, when applied correctly, removes localized stubborn residues from alumina crucibles while limiting damage to the ceramic substrate.

Mechanical cleaning helps where metal-rich or glassy residues resist both thermal cycling and moderate chemical baths. Furthermore, by restricting abrasion to selected areas and using tools softer than alumina, users can restore usable surface without introducing deep scratches. Nevertheless, indiscriminate scraping with hard metal tools accelerates wear, so this method must be used sparingly and with clear criteria.

Selecting Tools Softer Than the Alumina Body

Because alumina crucibles typically reach Vickers hardness values between 13 and 18 GPa, cleaning tools should remain significantly softer. Many facilities therefore choose plastic or wood scrapers for general work and reserve fine silicon carbide papers only for extreme cases. Additionally, worn diamond files, although harder, can be used in very localized spots when replacement is already being considered.

In practice, a three-stage approach is common: users first test whether residues loosen after chemical soaking by using a polypropylene spatula; next, they may move to a dense hardwood stick for slightly more pressure; finally, ultra-fine abrasive papers between 800 and 1200 grit are reserved for persistent spots near the rim where structural risk is lower. Each step is documented so that cumulative material removal on alumina crucibles stays within acceptable limits.

To quantify wear, some labs weigh crucibles before and after mechanical cleaning and limit total mass loss over their service life to around 2–3%.

Combining Mechanical Action with Previous Methods

Mechanical cleaning rarely works alone; instead, it complements thermal and chemical steps. For example, thermal burnout may first convert sticky residues into brittle ash, which is then easier to dislodge with a soft scraper. Similarly, chemical soaking can weaken the interface between glassy slags and alumina, so that only a few passes with fine abrasive are needed.

After each mechanical pass, it is helpful to inspect the surface under good lighting or low-magnification optics. Any new scratch that exceeds approximately 0.1 mm in width or depth should be considered a potential crack initiator, especially near the bottom radius of the alumina crucibles where stresses concentrate. Consequently, users may restrict mechanical work in highly stressed areas and accept small residual stains that no longer influence process chemistry.

In many industrial sites, a guideline is adopted that limits mechanical cleaning to no more than three full cycles for each crucible over its lifetime, with all other cleanings relying on thermal and chemical methods.

Typical Mechanical-Assisted Cleaning Scenarios

| Situation | Pre-treatment used | Mechanical tool applied | Target area on alumina crucibles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brittle carbon after burnout | Thermal cleaning at 750–850°C | Polypropylene spatula | Entire inner surface, low pressure |

| Weakened glass after NaOH soak | Chemical cleaning at 60°C | Hardwood stick | Local bottom pools and side streaks |

| Local metal inclusion near rim | Acid soak at room temperature | 800–1200 grit SiC paper | Upper 5–10 mm from rim only |

Case Study: Japanese Manufacturing Plant (K. Suzuki)

K. Suzuki, part of the engineering team at a Japanese manufacturing company producing specialty glass powders, faced repeated problems with alumina crucibles showing thick glassy rings after long sintering cycles. Thermal and alkali cleaning reduced residues but still left uneven layers that caused samples to stick and chipped when removed.

To address this, Suzuki introduced a combined method: alumina crucibles first underwent a 6% NaOH soak at 55°C for two hours, followed by a gentle rinse. Afterwards, operators used a custom-shaped hardwood stick to apply light pressure along the softened glass ring, which flaked off in narrow segments. Finally, any remaining islands near the top edge were polished with 1000-grit silicon carbide paper under running water.

After adopting this approach, average crucible life increased from about 80 cycles to nearly 150 cycles, and incidents of glass flaking into subsequent batches dropped by roughly 70%. Because mechanical work was limited mainly to non-critical areas, structural failures did not increase, confirming that the controlled method was compatible with long-term use of alumina crucibles.

Some operating conditions push alumina crucibles close to their temperature limits; cleaning them requires special caution beyond the standard methods described above.

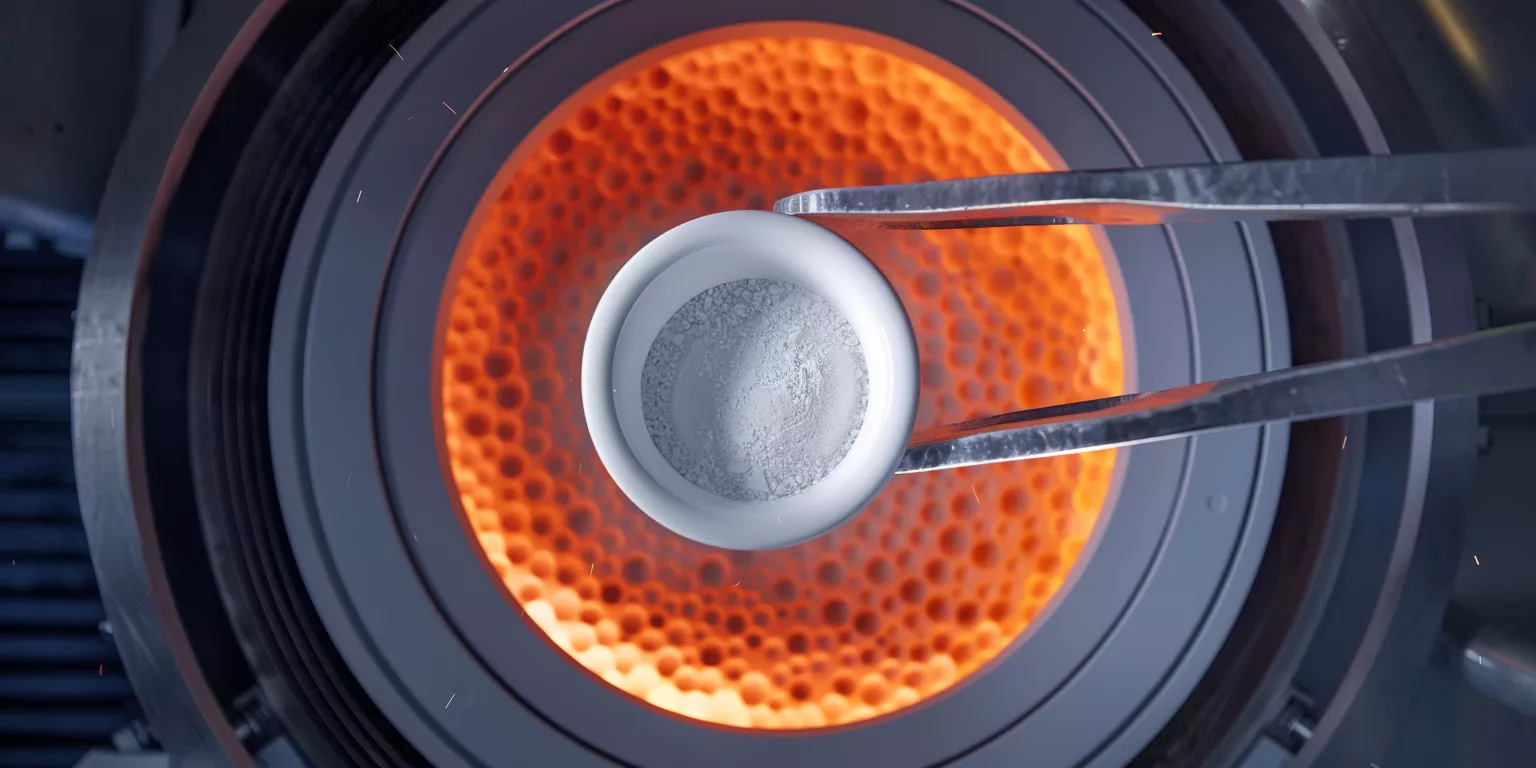

Method 4: High-Temperature (>1600°C) Reaction Residue Cleaning

Alumina crucibles exposed to temperatures above 1600°C often exhibit microstructural changes and severe slags that demand conservative cleaning strategies.

High-temperature applications such as advanced ceramic sintering or specialized alloy melting push alumina crucibles close to their structural and chemical limits. Consequently, their surfaces may partially react with samples or fluxes, forming complex layers that no longer behave like simple contaminants. Therefore, cleaning efforts must balance recovery of function against the risk of exposing a weakened substrate that could fail in future runs.

Microstructural Changes After Extreme Service

At temperatures exceeding roughly 1650°C, grain growth in alumina accelerates and porosity may change, especially at the hot face of crucibles. When aggressive slags are present, reaction layers can grow to several hundred micrometers in thickness. In such cases, removal of all visible residue might actually reveal a heavily attacked zone whose remaining strength is significantly lower than that of fresh material.

Moreover, repeated high-temperature cycling can change the thermal expansion behavior of the near-surface region of alumina crucibles. This means that even if cleaning appears successful, subtle mismatches between inner and outer layers may increase the probability of spalling under future thermal gradients. Consequently, conservative criteria for continued use are justified after each deep cleaning.

Because of these concerns, many users limit high-temperature alumina crucibles to a defined maximum number of cycles, such as 50–80, regardless of cleaning success, and then retire them to lower temperature duties.

Conservative Cleaning Steps for High-Temperature Cracking Risk

When alumina crucibles have seen temperatures above 1600°C, thermal cleaning should use slower ramps and lower peak temperatures than those used during operational firing. For example, a burnout at 1300–1400°C may be sufficient to remove remaining organics without driving further grain growth. Chemical cleaning should also be gentler, using lower acid or alkali concentrations and shorter soaking periods.

Non-destructive checks such as tapping tests or dye-penetrant inspection around the outer wall can help reveal accumulated cracking. If a crucible emits a dull sound where it once rang clearly, this suggests internal damage; continued heavy cleaning is rarely justified. Instead, the crucible may be reassigned to non-critical tasks like pre-calcination of raw powders where failure risk carries less impact.

Typical Parameters for High-Temperature Service Crucible Cleaning

| Previous maximum use temperature (°C) | Recommended burnout limit (°C) | Suggested chemical solution strength | Maximum remaining critical cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1600–1650 | 1300–1400 | 10–15% of standard concentration | 40–60 |

| 1650–1700 | 1300–1350 | 5–10% of standard concentration | 20–40 |

| >1700 | 1200–1300 | Chemical cleaning only for local areas | 0–20 (often downgraded duty) |

Case Study: US Foundry Systems Operation (M. Rivera)

M. Rivera, Operations Lead at a US-based foundry systems supplier, managed alumina crucibles used for trial melts near 1700°C with aggressive oxide slags. After several test campaigns, cleaning staff reported that even mild chemical and mechanical procedures caused rims to chip unexpectedly, raising concerns about hidden damage.

Rivera implemented a stricter classification system. Alumina crucibles that had exceeded 1650°C were tagged with a high-temperature label, and their maximum additional uses were capped at 30 cycles after the first full cleaning. The cleaning protocol was adjusted to limit burnout temperatures to 1300°C and to use diluted acid solutions at half the previous concentration, applied only to local slag rings.

Over one year, the plant observed a 50% reduction in sudden crucible failures, while overall consumable cost increased only slightly because fewer extremely stressed crucibles were kept in service beyond their safe life ceiling. Rivera concluded that accepting earlier retirement for heavily loaded alumina crucibles was preferable to chasing marginal cleaning gains that risked costly furnace incidents.

Even the best cleaning methods have limits; users need clear criteria to decide when continued efforts are no longer justified and replacement is the safer option.

When to Stop Cleaning and Replace the Crucible

Certain visual and functional indicators on alumina crucibles show that further cleaning will not restore safe, reliable performance and that replacement is the rational choice.

Structural Damage Indicators

When alumina crucibles show through-wall cracks, chips larger than about 3 mm along the rim, or measurable warping beyond 1–2% of diameter, the probability of failure during the next cycles rises sharply and replacement should be prioritized.

Persistent Contamination After Multiple Cycles

If two or three full cleaning cycles still leave thick, adherent layers that cover more than 30–40% of the interior surface, or if previous residues clearly alter new sample color or wetting behavior, the crucible is no longer suitable for precise work and should be retired.

Life-Cycle and Traceability Limits

In many controlled operations, alumina crucibles receive a unique ID and maximum cycle count, often between 300 and 500 for moderate duty. Once this limit is reached, they are removed from critical processes regardless of current appearance.

Replacement Thresholds Overview

| Indicator type | Typical threshold value for replacement | Rationale for alumina crucibles retirement |

|---|---|---|

| Crack or chip size | Defect > 3 mm or visible through-wall | High probability of sudden failure under heating |

| Residue coverage | >35% of internal surface after full cleaning | Unacceptable risk of cross-contamination |

| Total use cycles | Above documented maximum for duty level | Statistical increase in breakage and leakage risk |

Good cleaning can be amplified by everyday practices that slow down wear and contamination, thereby extracting the full value from alumina crucibles.

Best Practices to Extend Alumina Crucible Service Life

Service life of alumina crucibles increases when users combine gentle firing schedules, correct loading, and disciplined cleaning cycles with proper storage and handling.

Routine practices that seem minor individually can, in combination, extend usable life of alumina crucibles by a factor of 1.5–2.0. Moreover, they often cost little or nothing to implement, as they depend mainly on operator training and simple procedural changes. Therefore, sites that treat crucibles as critical assets rather than disposable items usually see measurable cost and reliability benefits.

Optimized Firing Profiles and Loading Practices

Avoiding excessively steep heating or cooling ramps is one of the easiest ways to reduce thermal stress. For many applications, limiting effective ramp rates to 3–5°C per minute and ensuring uniform load distribution inside alumina crucibles keeps temperature gradients manageable. In addition, placing powders or parts so that they do not create extreme local hot spots reduces differential expansion.

Repeated overfilling is another hidden enemy of crucible life. When material regularly reaches the rim, spillage and frozen overflows tend to create mechanical leverage points that chip the edge during handling. As a result, many plants set a maximum fill height of 70–80% of internal depth for alumina crucibles used in demanding thermal cycles.

Storage, Handling, and Documentation Habits

Between uses, alumina crucibles should be stored on padded shelves or in trays where rims do not contact hard surfaces. Stacking more than two or three units inside each other is discouraged, because small misalignments can create concentrated stresses that only become visible later as radial cracks. Instead, some users adopt custom foam or ceramic racks that hold crucibles in vertical rows.

Simple documentation also helps. Recording the number of cycles, type of service, and last cleaning method for each group of alumina crucibles allows engineers to link failures to specific practices. Over time, this data supports optimization of ramp rates, chemical exposure limits, and retirement thresholds for each duty class.

Typical Targets for Extended Service Life Programs

| Practice area | Recommended target for alumina crucibles | Expected life extension factor | Example measurement metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heating / cooling ramps | ≤5°C/min for routine cycles | 1.2–1.4× | Mean cycles before first failure |

| Fill height | ≤80% of internal depth | 1.1–1.3× | Fraction of crucibles with chipped rims |

| Cleaning schedule | Defined after X uses (e.g., every 5–10) | 1.3–1.6× | Share of crucibles within spec after 300 cycles |

Even well-designed methods occasionally produce unexpected results; a concise troubleshooting framework helps users quickly diagnose and correct common problems during alumina crucibles cleaning.

Troubleshooting Common Cleaning Problems

Troubleshooting issues that arise while cleaning alumina crucibles prevents minor deviations from turning into recurring defects or premature failures.

Black Stains That Persist After Thermal Burnout

When dark stains remain after standard burnout, the furnace atmosphere may be oxygen-poor, or heating time may be insufficient. In many cases, extending dwell time by 30–60 minutes or slightly increasing maximum temperature within limits resolves the issue.

Milky or Roughened Surface After Chemical Cleaning

If alumina crucibles develop a milky appearance or feel significantly rougher after soaking, the solution concentration or temperature is likely too high. Reducing both by 30–50% and shortening exposure usually prevents further degradation.

New Cracks Appearing After Mechanical-Assisted Cleaning

Fresh cracks appearing shortly after mechanical work indicate that tools were too hard or pressure too high. Restricting abrasion to localized, non-critical zones and using softer scrapers can stop this pattern.

Troubleshooting Guide for Typical Cleaning Issues

| Observed problem | Likely root cause | Primary corrective action for alumina crucibles |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent black staining | Insufficient oxygen or dwell time | Increase burnout time or airflow |

| Surface becomes dull and chalky | Overly strong acid / alkali or high temperature | Dilute solution and shorten soak |

| New cracks near rim | Excessive mechanical pressure | Switch to softer tools and reduce force |

| Residues redeposit after rinsing | Dirty rinse water or inadequate flow | Use fresh deionized water and longer rinse |

In summary, users who treat cleaning as an integral part of process design will obtain more consistent results and longer-lasting alumina crucibles.

Conclusion

Consistent, residue-specific cleaning combined with realistic replacement rules protects both data quality and furnace uptime for alumina crucibles.

If your current alumina crucibles often fail earlier than expected or contribute to noisy analytical results, review your contamination types, safety practices, and cleaning parameters using this guide as a benchmark. Then, document a standard operating procedure that your whole team can follow and refine over time.

FAQ

How often should alumina crucibles be cleaned?

Frequency depends on loading and chemistry, but many labs clean alumina crucibles after every 5–10 cycles for moderate duty. High-contamination applications such as flux fusion often justify at least a light cleaning after each use, followed by a deeper chemical treatment every 5–10 runs.

Can household detergents be used for cleaning alumina crucibles?

Mild detergents help remove loose dirt or fingerprints but do little against metal oxides or flux residues. They are suitable as a pre-cleaning step before thermal or chemical treatment, yet they should not replace dedicated methods when alumina crucibles carry high-temperature contamination.

Does repeated chemical cleaning weaken alumina crucibles?

Yes, repeated exposure to strong acids or alkalis gradually etches the ceramic and reduces strength. When solution strength and soak time are optimized, weight loss per cycle can be kept below about 0.3–0.5%, which allows dozens of safe cleanings, but aggressive conditions will significantly shorten the life of alumina crucibles.

Is it safe to reuse alumina crucibles for different materials?

Reuse is acceptable only when cleaning removes residues to the point where they no longer influence new materials. For high-sensitivity analyses, many facilities dedicate groups of alumina crucibles to specific chemistries, because even trace cross-contamination of a few parts per million can be problematic in advanced materials and analytical work.

References:

-

Understanding relative error is crucial for accurate scientific analysis, as even small shifts can significantly impact research outcomes and data reliability. ↩

-

Understanding organic ash tests can enhance your knowledge of material properties and their behavior under heat. ↩

-

Learn about the significance of using FFP2 or N95 masks to protect against airborne dust in laboratory settings. ↩