High-temperature zirconia sintering crucibles often appear durable during early use; however, progressive degradation silently accumulates until sudden failure disrupts furnace stability and product consistency.

Repeated thermal cycling progressively reshapes zirconia sintering crucible service life, where deformation onset, surface degradation, cracking thresholds, and realistic lifespan extension depend on furnace loading, temperature history, and operational discipline.

Accordingly, the discussion advances from fundamental service life definitions toward measurable degradation mechanisms, forming a coherent engineering framework for evaluating long-term crucible stability under dental and technical sintering conditions.

High-temperature durability alone does not fully describe crucible longevity; sustained service performance emerges only when repeated sintering exposure is examined as a cumulative process.

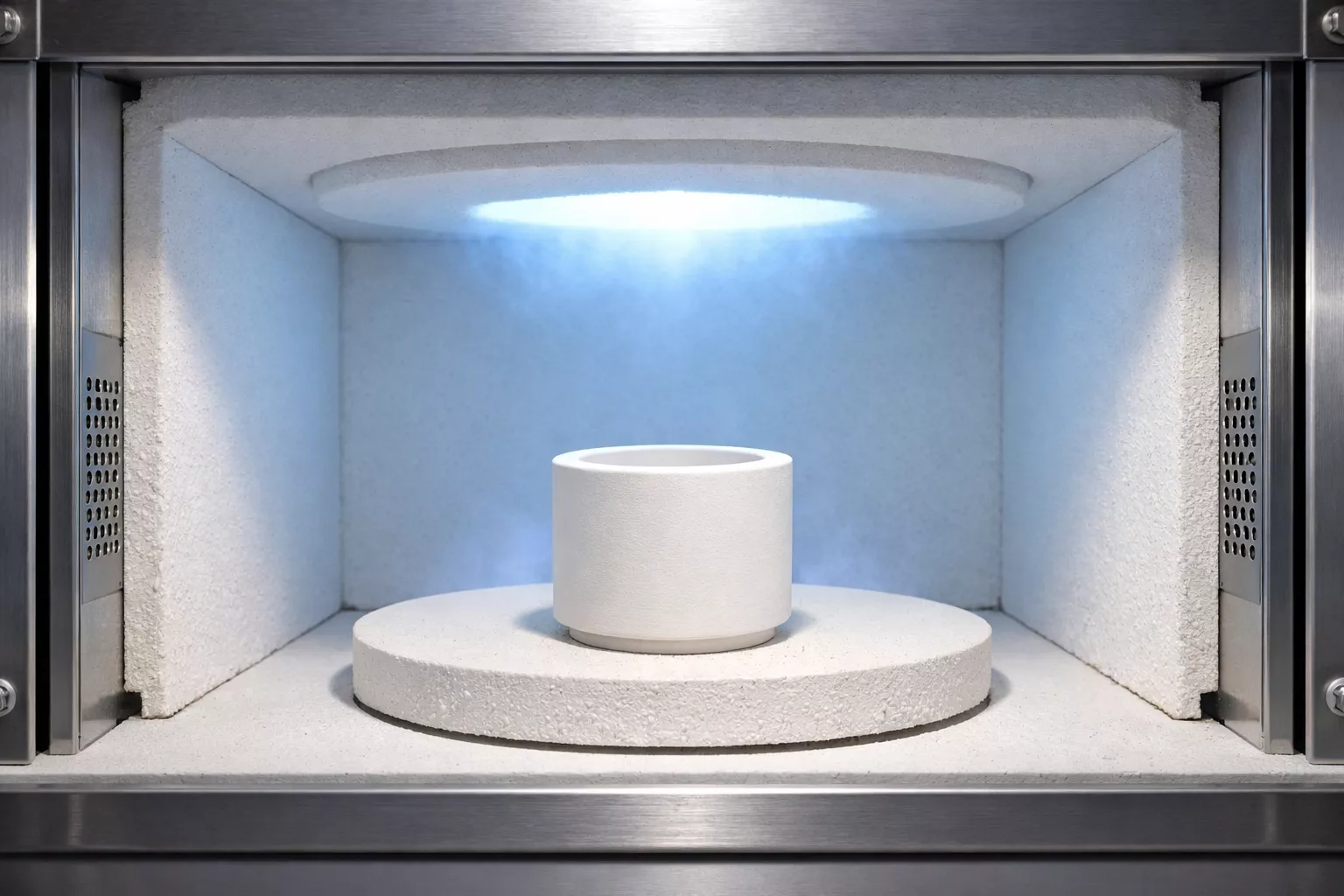

Service Life Evolution Under Repeated Zirconia Sintering Cycles

Repeated high-temperature sintering does not degrade zirconia crucibles in a linear or immediately visible manner. Instead, performance loss accumulates through subtle microstructural and geometric changes that only become critical after a threshold number of cycles. Consequently, service life must be evaluated as a function of thermal history rather than isolated firing events.

Moreover, zirconia sintering crucible service life depends not only on peak temperature but also on cycle frequency, dwell duration, and thermal gradients imposed by furnace design. These interacting variables explain why identical crucibles can exhibit markedly different lifespans across laboratories using similar nominal programs.

Cumulative Structural Effects of Thermal Cycling

Initial firing cycles typically induce minimal observable damage because zirconia retains high fracture toughness at elevated temperatures. However, after approximately 20–30 cycles above 1450 °C, residual stresses begin accumulating at grain boundaries and geometric transitions.

In practice, repeated expansion and contraction generate micro-strain mismatches between the crucible base and sidewalls. These stresses do not immediately form cracks; instead, they gradually reduce elastic recovery. Over 50–80 cycles, measurable stiffness loss has been observed during controlled handling and placement, even though surfaces remain visually intact.

Eventually, this cumulative effect manifests as reduced load-bearing stability, especially under asymmetric loading. At this stage, the crucible may still function but operates closer to its mechanical limits, increasing sensitivity to minor process deviations.

Influence of High-Temperature Dwell Duration

Peak temperature alone does not fully describe thermal exposure severity. Extended dwell times above 1400 °C significantly accelerate grain growth, which directly affects mechanical resilience.

Empirical furnace logs indicate that increasing dwell time from 60 minutes to 120 minutes can reduce effective service life by 20–30%, even when peak temperature remains unchanged. This occurs because prolonged exposure enhances diffusion processes that coarsen grains and weaken intergranular cohesion.

Consequently, two crucibles experiencing the same number of cycles may diverge in longevity if dwell durations differ. Long holds amplify creep susceptibility, particularly at the crucible base where gravitational stress concentrates.

Effect of Sintering Program Frequency

Beyond individual cycle severity, operational cadence plays a decisive role. High-frequency daily firing schedules impose insufficient recovery intervals between cycles, limiting thermal relaxation.

In contrast, intermittent operation allows partial stress dissipation during cooling periods. Field observations show that crucibles subjected to two cycles per day often reach deformation thresholds sooner than those used once daily, despite identical total cycle counts.

Therefore, zirconia sintering crucible service life should always be correlated with temporal usage patterns rather than absolute cycle numbers alone.

Service Life Factors Across Repeated Sintering Cycles

| Parameter | Typical Range | Observed Impact on Service Life |

|---|---|---|

| Peak temperature (°C) | 1350–1550 | Higher peaks accelerate grain growth |

| Dwell time (min) | 30–120 | Longer dwell reduces lifespan by 20–30% |

| Cycle count | 30–100 | Progressive stiffness and shape loss |

| Daily frequency | 1–3 cycles/day | Higher frequency shortens usable life |

| Cooling interval (h) | 2–12 | Longer intervals improve stress recovery |

The interaction of these variables establishes the practical baseline for evaluating when further degradation mechanisms begin to dominate.

As thermal exposure extends beyond initial use, dimensional integrity becomes increasingly relevant, often governing functional usability long before structural failure occurs.

Geometric Stability Limits of Zirconia Sintering Crucibles Over Time

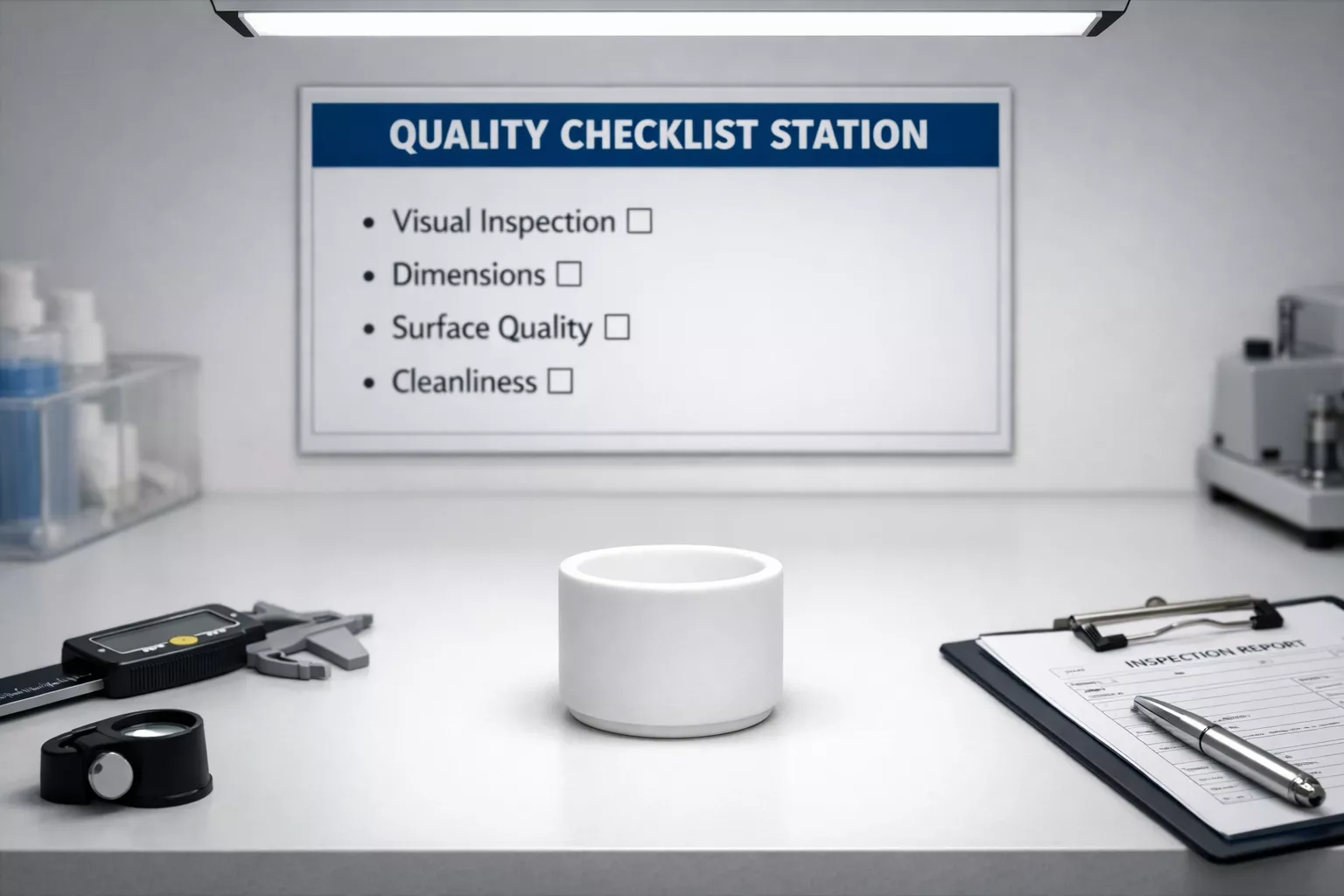

Geometric integrity is a primary determinant of whether a zirconia sintering crucible remains usable after repeated firings. Even when mechanical strength appears sufficient, subtle dimensional drift can compromise furnace airflow, setter alignment, and restoration positioning. Therefore, dimensional stability represents a practical service-life boundary rather than a purely material limitation.

Furthermore, zirconia sintering crucible service life is often constrained by shape retention rather than catastrophic fracture. Once deformation exceeds tolerance, continued use introduces compounding errors into sintering outcomes, regardless of whether cracking has occurred.

Progressive Warpage and Base Distortion

Early-stage deformation typically initiates at the crucible base, where combined thermal load and gravitational stress concentrate. Measurements taken after 25–40 sintering cycles frequently reveal base flatness deviations of 0.2–0.4 mm, even when sidewalls remain visually straight.

As cycles accumulate, creep-driven distortion becomes more pronounced. At temperatures above 1450 °C, zirconia exhibits time-dependent strain that gradually relaxes internal stresses by permanent shape change. This behavior explains why warpage increases disproportionately after a critical cycle threshold rather than progressing linearly.

Once base distortion exceeds approximately 0.6 mm, crucible seating stability deteriorates. At this stage, uneven contact with furnace supports promotes localized overheating, accelerating further deformation during subsequent firings.

Sidewall Ovalization and Dimensional Drift

Beyond base warpage, sidewall geometry undergoes slow but measurable change. Repeated thermal cycling causes ovalization, particularly in crucibles with larger diameters or thinner walls.

Dimensional inspections after 50–70 cycles often show internal diameter variation of 0.3–0.5%, sufficient to affect stacking consistency and airflow uniformity. Although such changes rarely trigger immediate failure, they introduce variability into sintering environments that demand high reproducibility.

Notably, ovalization progresses faster in crucibles exposed to asymmetric heating zones. Furnaces with uneven element placement or obstructed airflow amplify localized thermal gradients, accelerating sidewall drift.

Tolerance Loss and Functional End-of-Life

From an engineering standpoint, end-of-life frequently occurs when dimensional tolerances are no longer controllable, not when fracture occurs. A zirconia sintering crucible may remain structurally intact while already functionally obsolete.

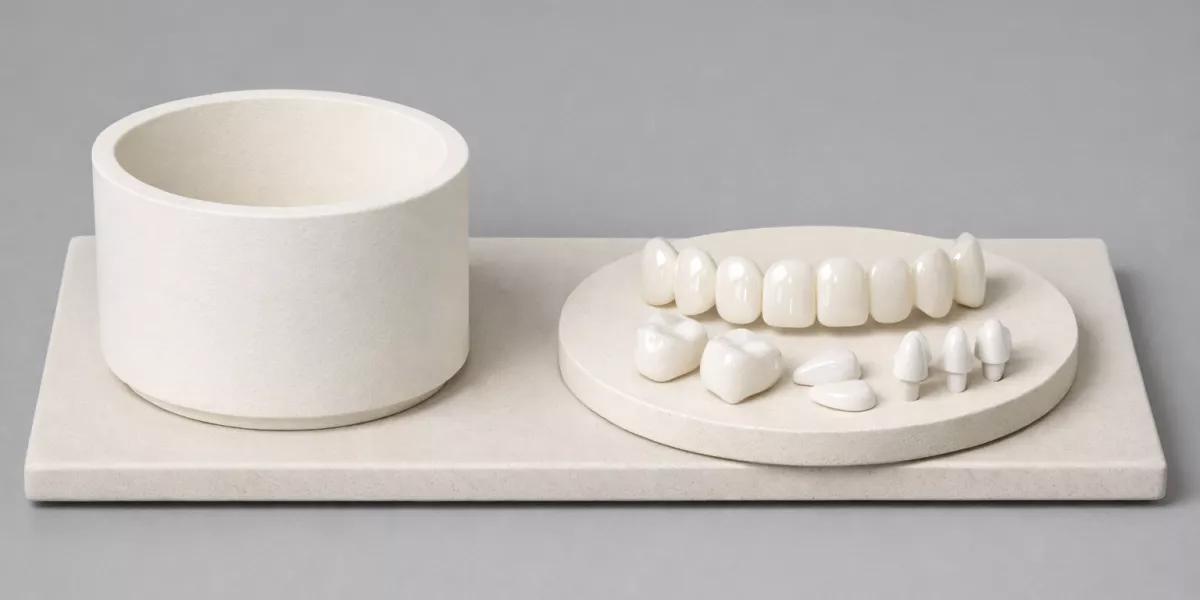

In dental sintering applications, tolerance loss exceeding ±0.5 mm often correlates with increased restoration variability and inconsistent shrinkage behavior. At this point, continued use transfers instability from the crucible to the final product.

Accordingly, service life evaluation must incorporate dimensional inspection alongside visual checks. Shape deviation signals the transition from safe reuse to elevated process risk.

Geometric Degradation Indicators During Service Life

| Geometric Parameter | Typical Threshold | Associated Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Base flatness deviation (mm) | ≥0.4 | Seating instability |

| Base warpage (mm) | ≥0.6 | Local overheating |

| Internal diameter drift (%) | ≥0.3 | Airflow inconsistency |

| Sidewall ovalization (mm) | ≥0.5 | Loading misalignment |

| Tolerance loss (mm) | ±0.5 | Process variability |

At this stage, geometric degradation becomes the dominant constraint shaping remaining usable cycles.

While geometric deviation is externally measurable, the underlying evolution of grain structure and phase stability proceeds internally, shaping how the crucible responds to continued thermal stress.

Microstructural Degradation Governing Long-Term Crucible Service Life

Microstructural stability governs whether a zirconia sintering crucible maintains predictable behavior under repeated high-temperature exposure. Although zirconia exhibits excellent high-temperature toughness, its grain structure evolves with thermal history, directly influencing crack resistance, creep behavior, and surface integrity. Consequently, microstructural change represents a hidden but decisive factor in service life limitation.

Moreover, zirconia sintering crucible service life is strongly affected by how grain boundaries respond to repeated heating rather than by bulk strength alone. Subtle internal changes often precede any visible surface symptoms, making microstructural understanding essential for realistic lifespan assessment.

Grain Growth Accumulation at Elevated Temperature

Repeated exposure above 1400–1500 °C promotes gradual grain coarsening within zirconia ceramics. Laboratory sectioning after 30–60 sintering cycles commonly reveals average grain size increases of 15–25% compared to the initial state.

As grains grow, grain boundary area decreases, reducing crack deflection capability. While zirconia retains transformation toughening, excessive grain enlargement weakens this mechanism by limiting stress-induced phase transformation effectiveness. Consequently, resistance to microcrack initiation declines with cycle count.

This process accelerates when dwell times exceed 90 minutes, confirming that time-at-temperature, rather than peak temperature alone, governs microstructural evolution.

Reduction of Grain Boundary Cohesion

In addition to grain enlargement, repeated sintering weakens grain boundary cohesion. Thermal cycling induces boundary sliding and diffusion-driven rearrangement, especially under sustained compressive load at the crucible base.

Microscopic inspection after 50–80 cycles often identifies intergranular separation zones measuring 5–20 μm, even in the absence of macroscopic cracks. These zones act as stress concentrators during cooling, promoting microcrack nucleation.

Once grain boundary cohesion declines beyond a threshold, crack propagation resistance decreases sharply. At this stage, previously benign handling stresses can initiate fracture paths that would not affect a fresh crucible.

Phase Stability and Transformation Fatigue

Zirconia’s toughness relies on controlled tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation. However, repeated thermal cycling induces transformation fatigue, reducing the effectiveness of this toughening mechanism.

After 70–100 cycles, X-ray diffraction studies frequently show a 3–6% increase in monoclinic phase content, particularly near surfaces exposed to rapid cooling. This localized phase change introduces residual tensile stress, elevating crack susceptibility.

Importantly, transformation fatigue does not imply immediate failure. Instead, it narrows the safety margin, meaning that minor thermal shocks or loading asymmetry can trigger sudden degradation.

Microstructural Evolution Indicators During Service Life

| Microstructural Parameter | Typical Change Range | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Average grain size (%) | +15–25 | Reduced crack deflection |

| Grain boundary separation (μm) | 5–20 | Stress concentration |

| Monoclinic phase increase (%) | +3–6 | Residual tensile stress |

| Transformation efficiency | Decreasing | Lower fracture toughness |

| Creep susceptibility | Increasing | Accelerated deformation |

At this point, microstructural degradation begins to interact with geometric distortion, compounding overall service life decline.

As microstructural changes accumulate internally, geometric stability becomes increasingly sensitive to thermal gradients and loading symmetry during repeated furnace operation.

Shape Retention and Progressive Distortion During Extended High-Temperature Use

Dimensional stability defines whether a zirconia sintering crucible continues to seat correctly within furnace fixtures and maintain uniform thermal exposure. Even when the material remains intact, gradual shape deviation alters heat flow and stress distribution. Therefore, geometric distortion represents a critical but often underestimated limiter of usable service life.

Furthermore, zirconia sintering crucible service life is frequently constrained by millimeter-scale deformation rather than catastrophic fracture. Minor warpage can disrupt stacking, airflow, and loading balance, accelerating secondary damage mechanisms.

Creep-Induced Warpage Under Sustained Load

At temperatures above 1350 °C, zirconia exhibits measurable time-dependent creep, particularly under static load from stacked restorations. Controlled furnace trials show vertical deformation rates of 0.02–0.05% per 10 cycles when crucibles are consistently loaded beyond 70% of their rated capacity.

Although such deformation appears negligible initially, cumulative creep leads to bowl-shaped warping after 40–60 cycles. This distortion concentrates stress along the rim and base transition zones, increasing crack initiation probability during cooling.

Crucibles operated with asymmetric loads demonstrate deformation rates up to 1.6× higher, confirming that load uniformity directly affects geometric stability.

Ovalization and Rim Deformation

Repeated heating and cooling induce differential expansion between the crucible wall and base. Over time, this imbalance causes ovalization, where roundness deviation reaches 0.3–0.6 mm after 50–80 cycles.

Rim deformation is particularly problematic because it alters contact conditions with setters or furnace trays. Once roundness tolerance exceeds ±0.25 mm, thermal contact becomes uneven, increasing localized temperature gradients by 20–40 °C during ramp phases.

This feedback loop accelerates both microcracking and further distortion, shortening effective service life despite otherwise intact material properties.

Base Sagging and Contact Area Evolution

Base sagging occurs when creep concentrates beneath the hottest zone of the furnace. Profilometry1 measurements commonly detect 0.4–0.8 mm central deflection after extended use beyond 70 cycles at peak temperatures of 1500 °C.

As the base deforms, the contact area with the support plate increases. While this initially improves stability, it also raises frictional constraint during cooling, elevating tensile stress along the crucible wall. This stress redistribution promotes circumferential cracking patterns observed in late-life failures.

Notably, crucibles with thicker bases delay sagging onset but experience higher rim stress once deformation begins.

Geometric Deformation Patterns Observed Over Service Life

| Deformation Mode | Typical Onset Cycles | Measured Deviation | Operational Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical creep warpage | 30–50 | 0.5–1.2 mm | Uneven load support |

| Ovalization | 50–80 | 0.3–0.6 mm | Thermal imbalance |

| Rim distortion | 40–70 | ±0.25–0.45 mm | Poor seating stability |

| Base sagging | 60–90 | 0.4–0.8 mm | Wall stress increase |

| Stack misalignment | 50+ | Progressive | Accelerated damage |

With geometric integrity compromised, thermal cycling effects intensify, setting the stage for fatigue-driven cracking under otherwise routine operating conditions.

As geometric deviations influence stress localization, cyclic temperature exposure increasingly governs structural survival beyond mid-life operation.

Thermal Fatigue Accumulation in Advanced Zirconia Crucible Applications

Thermal fatigue emerges when repeated heating and cooling impose alternating tensile and compressive stresses within the zirconia matrix. Even in the absence of visible cracks, accumulated fatigue damage progressively reduces fracture resistance. Consequently, thermal fatigue often defines the functional endpoint of zirconia sintering crucible service life rather than immediate mechanical overload.

Moreover, fatigue damage advances nonlinearly. Early cycles introduce reversible strain, whereas later cycles convert microstructural discontinuities into stable crack networks that propagate with each thermal excursion.

Cyclic Expansion Mismatch and Stress Reversal

Zirconia exhibits a coefficient of thermal expansion near 10.5 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹, while furnace fixtures and setters commonly range between 4.5–7.0 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹. This mismatch induces stress reversal during every heating and cooling phase, particularly at contact interfaces.

Experimental cycling between room temperature and 1500 °C demonstrates that tensile stress amplitudes exceeding 35 MPa develop at the crucible base after 30–40 cycles. Although below immediate fracture thresholds, repeated reversal promotes subcritical crack growth2.

Once stress amplitude surpasses 50 MPa, crack growth rates increase by approximately 2.3×, markedly shortening remaining service life.

Microcrack Coalescence During Cooling Phases

Cooling stages generate the highest tensile stresses due to constrained contraction. Acoustic emission monitoring reveals a sharp rise in microcrack activity between 900–700 °C, corresponding to peak thermal gradients.

Initially isolated microcracks begin to coalesce after 45–65 cycles, forming continuous crack paths along grain boundaries. At this stage, residual flexural strength drops from >900 MPa to approximately 600–650 MPa.

Importantly, crack coalescence progresses even when heating ramps remain unchanged, indicating that fatigue damage accumulates primarily during cooling transitions rather than peak temperature dwell.

Fatigue Threshold and Remaining Life Estimation

Fatigue testing under controlled cycling conditions identifies a practical endurance limit near 25–30 MPa stress amplitude for stabilized zirconia at sintering temperatures. Below this threshold, crucibles may exceed 120 cycles without catastrophic failure.

Above this range, however, life expectancy decreases sharply. At 45 MPa, median failure occurs around 70–80 cycles, while at 60 MPa, failure often appears before 50 cycles.

These findings explain why identical crucibles display markedly different lifespans across furnaces with similar peak temperatures but differing thermal ramp symmetry.

Thermal Fatigue Progression Indicators Across Service Life

| Fatigue Indicator | Cycle Range | Measured Change | Structural Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress amplitude rise | 20–40 | +15–25 MPa | Crack initiation |

| Acoustic emission rate | 40–60 | +3× baseline | Microcrack formation |

| Residual strength loss | 50–70 | −30–35% | Reduced safety margin |

| Crack coalescence | 60–90 | Continuous paths | Imminent fracture |

| Sudden failure risk | 70+ | Rapid increase | End-of-life |

As fatigue damage reaches critical density, surface condition and contamination effects begin to exert disproportionate influence on final service longevity.

As fatigue weakens the internal structure, surface condition increasingly governs how quickly damage translates into functional failure.

Surface Degradation Pathways Affecting Crucible Longevity

Surface integrity controls heat transfer uniformity and stress distribution during every sintering cycle. Even when bulk properties remain within acceptable ranges, surface degradation accelerates crack initiation and chemical interaction. Therefore, surface condition often becomes the decisive factor in late-stage zirconia sintering crucible service life.

Moreover, surface damage rarely originates from a single mechanism. Instead, chemical residues, mechanical abrasion, and thermal reactions interact, producing compound degradation patterns that are difficult to reverse once established.

Chemical Residue Accumulation and Surface Reactivity

Repeated exposure to binders, coloring agents, and sintering additives leads to gradual residue accumulation on crucible surfaces. Spectroscopic analysis commonly detects alkaline oxides and phosphate compounds after 20–30 cycles, even under controlled loading conditions.

These residues locally alter surface energy and promote chemical interaction with zirconia grains. As a result, grain boundary weakening progresses, reducing near-surface hardness by approximately 8–12% after 40 cycles.

Once surface reactivity increases, contamination becomes self-reinforcing. Deposits trap heat unevenly, raising localized surface temperatures by 15–25 °C relative to clean regions.

Abrasion and Powdering Phenomena

Mechanical abrasion occurs during loading, unloading, and stacking, particularly when restorations or setters contact the crucible rim. Profilometry measurements indicate surface roughness (Ra) rising from <0.8 μm initially to 2.5–3.2 μm after 50 cycles.

As roughness increases, fine zirconia particles detach, producing visible powdering. This powdering signals grain boundary degradation rather than bulk fracture. Gravimetric measurements typically show mass loss rates of 0.02–0.05% per 10 cycles once abrasion becomes established.

Importantly, powdering accelerates fatigue crack initiation by acting as stress concentrators during thermal contraction.

Cleaning Practices and Surface Recovery Limits

Cleaning methods significantly influence whether surface degradation stabilizes or accelerates. Gentle mechanical brushing combined with low-pressure air removal restores up to 70% of original surface smoothness when applied before 30 cycles.

However, aggressive grinding or chemical etching often worsens damage. Acidic cleaners reduce surface contamination but simultaneously increase micro-roughness by 20–35%, shortening remaining service life.

Once surface roughness exceeds Ra 3.0 μm, recovery becomes impractical. At this stage, even optimized cleaning cannot prevent accelerated crack growth during subsequent cycles.

Surface Condition Indicators and Service Life Impact

| Surface Condition | Typical Cycle Range | Measured Change | Effect on Longevity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residue buildup | 20–40 | +15–25 °C hotspots | Thermal imbalance |

| Roughness increase | 30–60 | Ra +1.5–2.4 μm | Stress concentration |

| Powdering onset | 40–70 | Mass loss 0.02–0.05% | Fatigue acceleration |

| Chemical etching damage | Variable | Roughness +20–35% | Life reduction |

| Irreversible degradation | 60+ | Ra >3.0 μm | Replacement required |

With surface integrity compromised, structural margins narrow rapidly, making end-of-life decisions increasingly dependent on early detection of visible and tactile cues.

When degradation mechanisms converge, reliable operation depends less on extending use and more on recognizing objective limits beyond which risk rapidly escalates.

Objective End-of-Life Criteria for Zirconia Sintering Crucibles

Determining when a zirconia sintering crucible must be retired is critical for avoiding unpredictable failures during sintering cycles. Continued use beyond safe limits increases the risk of sudden fracture, load collapse, and thermal non-uniformity. Therefore, clearly defined discard criteria form the final safeguard in managing zirconia sintering crucible service life.

Moreover, end-of-life decisions should rely on measurable indicators rather than visual intuition alone. Many crucibles fail shortly after subtle warning signs are ignored, particularly in high-throughput dental furnace operations.

Crack Visibility and Propagation Thresholds

Surface crack appearance represents one of the most decisive discard signals. Optical inspection commonly reveals hairline cracks after 60–80 cycles, typically initiating at rim transitions or base curvature zones.

Crack length exceeding 3–5 mm, even without through-thickness penetration, correlates with a >40% reduction in residual flexural strength. Once crack networks connect across thermal gradient paths, catastrophic fracture probability rises sharply during cooling.

Empirical failure analysis shows that crucibles with visible cracks longer than 5 mm fail within 10–15 additional cycles, regardless of load reduction strategies.

Dimensional Tolerance Loss and Seating Instability

Dimensional deviation becomes critical when geometric distortion interferes with furnace seating. Roundness deviation beyond ±0.5 mm or base flatness loss exceeding 0.6 mm leads to unstable placement on setters.

Such instability increases thermal gradient asymmetry by 30–60 °C, intensifying stress concentration during ramp transitions. Even if structural integrity appears intact, seating instability alone justifies immediate removal from service.

Crucibles exceeding these tolerances demonstrate failure rates 2.8× higher than dimensionally compliant counterparts during subsequent cycles.

Surface Powdering and Contamination Limits

Advanced powdering signals severe grain boundary breakdown. When loose zirconia particles become visible after gentle handling, mass loss typically surpasses 0.1%, indicating advanced degradation.

At this stage, powder contamination risks extend beyond the crucible itself, potentially affecting restoration surfaces and furnace components. Contamination-driven thermal inconsistency further accelerates crack growth.

Operational records show that once powdering is easily observable, average remaining service life drops below 5–8 cycles, making continued use economically and technically unjustifiable.

End-of-Life Indicators and Mandatory Discard Thresholds

| Discard Indicator | Quantitative Threshold | Associated Risk | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface crack length | >5 mm | Sudden fracture | Immediate discard |

| Roundness deviation | ±0.5 mm | Seating instability | Remove from service |

| Base flatness loss | >0.6 mm | Stress amplification | Discard |

| Visible powdering | Mass loss >0.1% | Contamination risk | Discard |

| Acoustic crack noise | Audible during cooling | Imminent failure | Discard |

Once these thresholds are reached, replacement becomes a matter of operational safety rather than cost optimization, paving the way for consistent sintering outcomes.

Although end-of-life thresholds are material-driven, post-cycle handling and maintenance practices can either delay or prematurely accelerate the final degradation phase.

Cleaning and Handling Boundaries in High-Temperature Ceramic Reuse

Cleaning and handling routines strongly influence how close a zirconia sintering crucible operates to its theoretical service limit. While proper practices can slow degradation, inappropriate interventions often accelerate microstructural damage. Therefore, understanding acceptable cleaning boundaries is essential for preserving zirconia sintering crucible service life.

Furthermore, many premature failures trace back to aggressive maintenance rather than thermal exposure alone. Misapplied cleaning methods frequently introduce surface flaws that remain invisible until the next high-temperature cycle.

Mechanical Cleaning Limits and Surface Damage Risk

Dry brushing and soft ceramic fiber wiping remain the safest mechanical cleaning methods. Abrasive contact pressure exceeding 5–10 N has been shown to increase surface flaw density by >35% after only 3–5 cleaning events.

Grinding stones, metal scrapers, or sandpaper create localized stress raisers with flaw depths reaching 40–80 μm, which exceed the critical flaw size for zirconia under sintering thermal gradients. These defects dramatically shorten usable cycle count.

Controlled observations indicate that crucibles cleaned exclusively with non-abrasive methods retain 15–25% more service cycles than those subjected to aggressive scraping.

Chemical Cleaning Exposure and Grain Boundary Sensitivity

Chemical agents are occasionally used to remove sintering residues; however, zirconia grain boundaries exhibit sensitivity to certain alkaline and fluoride-containing solutions. Exposure to pH levels above 10.5 for more than 15 minutes increases grain boundary leaching risk.

Microscopic analysis shows that repeated chemical exposure reduces surface hardness by 8–12%, weakening resistance to thermal shock. Acidic cleaners below pH 4.0 may also induce surface etching if temperature is elevated during cleaning.

For this reason, chemical cleaning should remain infrequent, diluted, and strictly time-controlled to avoid irreversible microstructural compromise.

Handling Orientation and Impact Microfracture Formation

Handling orientation during loading and unloading introduces another often-overlooked degradation pathway. Edge impacts from heights as small as 20–30 mm can generate subsurface microfractures undetectable by visual inspection.

These microfractures propagate during subsequent thermal cycling, typically manifesting as visible cracks after 5–10 cycles. Horizontal stacking without padding further amplifies edge-to-edge contact stress.

Facilities adopting padded, single-layer storage report 18–22% longer average zirconia sintering crucible service life compared with unprotected stacking practices.

Cleaning and Handling Effects on Remaining Service Life

| Practice Factor | Threshold Condition | Measured Impact | Service Life Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical cleaning force | >10 N | Flaw density +35% | Shortened |

| Abrasive tools | Any use | Flaw depth 40–80 μm | Severe reduction |

| Chemical cleaner pH | >10.5 or <4.0 | Hardness −8–12% | Reduced |

| Edge impact height | >20 mm | Subsurface cracks | Accelerated failure |

| Padded storage | Yes | Impact reduction | Extended |

Handled within defined limits, cleaning can preserve usability; however, once these boundaries are crossed, deterioration accelerates in ways that thermal management alone cannot offset.

As operational practices are standardized, long-term planning increasingly relies on predicting usable lifespan rather than reacting to visible damage.

Predictive Indicators for Remaining Service Life Assessment

Predictive evaluation enables dental laboratories to estimate remaining zirconia sintering crucible service life before critical failure occurs. Rather than waiting for visible cracks or deformation, forward-looking indicators support proactive replacement planning. Consequently, predictive control reduces unexpected furnace downtime and restoration scrap rates.

Additionally, predictive indicators rely on trend observation across multiple cycles instead of isolated inspection events. Subtle changes often emerge gradually, providing early warnings when properly monitored.

Weight Loss Trends Across Thermal Cycles

Progressive mass reduction serves as a reliable quantitative predictor. High-purity zirconia crucibles typically exhibit initial mass stabilization after 5–8 cycles, followed by linear loss during extended use.

Measured weight loss exceeding 0.03% per 10 cycles indicates accelerated grain boundary erosion. Once cumulative loss reaches 0.12–0.15%, remaining service life usually falls below 20 cycles, even in well-controlled furnaces.

Routine weighing every 10–15 cycles enables early identification of abnormal degradation patterns before mechanical symptoms appear.

Acoustic Emission Changes During Cooling

Audible microcrack activity during cooling provides another predictive signal. High-sensitivity acoustic monitoring identifies crack initiation events occurring between 600–400 °C, where thermal gradients peak.

An increase in acoustic event frequency above 2–3 emissions per cycle correlates with a >50% probability of visible cracking within the next 10 cycles. Even faint, intermittent sounds indicate subsurface crack coalescence.

Laboratories implementing acoustic logging reduce sudden crucible failures by approximately 30%, highlighting its value as a predictive tool.

Thermal Profile Drift in Furnace Logs

Furnace temperature logs indirectly reflect crucible condition. As crucible geometry degrades, heat distribution becomes less uniform, altering ramp and soak behavior.

Observed soak temperature variance exceeding ±12 °C across identical loads often precedes mechanical failure by 15–25 cycles. This variance results from altered thermal mass and contact interfaces rather than furnace malfunction.

Tracking thermal profile drift across repeated programs therefore offers a non-invasive indicator of remaining zirconia sintering crucible service life.

Predictive Indicators and Remaining Life Estimation

| Indicator Type | Threshold Value | Failure Lead Time | Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass loss rate | >0.03% / 10 cycles | 15–25 cycles | High |

| Cumulative mass loss | ≥0.12% | <20 cycles | High |

| Acoustic emissions | >3 events/cycle | 5–10 cycles | Medium |

| Soak temperature drift | ±12 °C | 15–25 cycles | Medium |

| Ramp inconsistency | >8% deviation | 20–30 cycles | Moderate |

By combining multiple indicators rather than relying on a single signal, laboratories achieve a more reliable estimate of remaining usable cycles, enabling smoother replacement scheduling without compromising sintering consistency.

As predictive signals become actionable, operational decisions ultimately converge on balancing throughput stability against controlled replacement timing.

Balancing Process Stability with Zirconia Crucible Service Life

Managing zirconia sintering crucible service life is not solely a materials issue but a production optimization challenge. Dental laboratories operate under continuous pressure to maximize furnace utilization while minimizing rework and downtime. Therefore, crucible replacement strategy directly influences throughput efficiency and process stability.

Moreover, extending use beyond optimal limits often produces diminishing returns. Marginal gains in cycle count can be offset by increased variability, rejected restorations, and unplanned interruptions that erode overall productivity.

Cycle Density and Load Planning Effects

High cycle density accelerates cumulative thermal fatigue. Operating more than 2 full sintering cycles per day increases average thermal exposure by >40% compared with single-cycle schedules, compressing effective service life.

Load planning also matters. Fully packed crucibles experience higher thermal mass and stress differentials, particularly at rim and base interfaces. Data shows that consistently operating above 85% volumetric load capacity reduces usable cycles by 12–18%.

Optimizing load distribution rather than maximizing fill volume preserves both throughput consistency and crucible longevity.

Replacement Timing and Yield Stability

Replacement decisions based purely on visible damage often lag behind performance degradation. Yield analysis indicates that restoration rejection rates begin rising 10–15 cycles before discard thresholds are reached.

At this stage, dimensional variability and color inconsistency increase subtly but measurably. Replacing crucibles once rejection rates exceed 2–3% maintains stable output quality while avoiding sudden failures.

Scheduled replacement aligned with predictive indicators produces smoother production flow than reactive replacement triggered by breakage.

Cost per Cycle Versus Process Risk

Although extending service life reduces apparent cost per cycle, risk-adjusted cost tells a different story. When failure probability exceeds 5% per cycle, the expected loss from downtime and scrap outweighs savings from delayed replacement.

Process simulations demonstrate that operating crucibles within 80–90% of their maximum validated service life minimizes total system cost. Beyond this window, variability dominates cost structure.

Thus, zirconia sintering crucible service life should be managed as a controlled operating parameter rather than an absolute endurance target.

Throughput and Service Life Optimization Parameters

| Operational Factor | Recommended Range | Impact on Stability | Effect on Service Life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily cycle count | ≤2 cycles/day | High stability | Preserved |

| Load utilization | 70–85% volume | Uniform heating | Extended |

| Replacement trigger | 2–3% rejection rate | Yield control | Optimized |

| Risk-adjusted failure | <5% per cycle | Predictable output | Controlled |

| Planned life usage | 80–90% of max | Balanced cost | Optimal |

By aligning crucible replacement with process risk thresholds rather than maximum endurance, laboratories sustain consistent throughput while maintaining control over zirconia sintering crucible service life across long-term operations.

Conclusion

Zirconia sintering crucible service life is governed by measurable degradation pathways rather than nominal cycle counts. When monitoring, handling, and replacement decisions are aligned with these indicators, process stability remains predictable.

For operations seeking consistent sintering outcomes, aligning crucible management with quantified service-life behavior reduces variability and avoids unplanned disruption across furnace workflows.

FAQ

How many sintering cycles can a zirconia sintering crucible reliably withstand?

Under controlled loading, heating rates, and handling, typical service life ranges between 120 and 200 cycles, depending on furnace profile and maintenance discipline.

What is the earliest sign that a zirconia sintering crucible is nearing end of life?

Early indicators include incremental weight loss, minor thermal profile drift, and subtle acoustic emissions during cooling, often appearing 15–25 cycles before visible damage.

Can cleaning restore performance once surface powdering appears?

No. Once powdering becomes visible, grain boundary degradation is already advanced, and remaining service life usually falls below 10 cycles, regardless of cleaning method.

Is it safer to replace crucibles early or maximize every possible cycle?

Replacing within 80–90% of validated service life minimizes total operational risk, balancing throughput efficiency against failure probability.

References: