Ceramic components can fail abruptly under heat and stress; consequently, zirconia demanded decades of scientific corrections before dependable service became possible.

Zirconia ceramics progressed from mineral curiosity to engineered oxide systems through phase control, defect chemistry, and microstructural discipline. Moreover, each breakthrough emerged from specific failure bottlenecks rather than incremental optimism.

Earlier sections establish how zirconia existed in nature long before laboratory isolation. Subsequently, chemical identification and phase science explain why zirconia resisted conventional ceramic logic, thereby setting up the later stabilization and toughening revolutions.

Before modern processing existed, zirconium-bearing minerals quietly shaped early high-temperature practices; moreover, natural occurrence explains why zirconia ceramic entered human history through geology rather than design.

Zirconia Ceramic as a Natural Substance in Early Human History

Zirconia ceramic history begins in mineral reservoirs rather than kilns. Likewise, geological dispersion and accidental thermal exposure created the first practical clues about refractoriness and inertness.

- Geological occurrence of zirconium-bearing minerals

Zircon ZrSiO41 dominates zirconium occurrence; consequently, zircon sands concentrate through weathering and hydraulic sorting. Additionally, hafnium commonly co-associates at roughly 1–3 wt% in zircon lattices, complicating later separation. As an illustration, heavy-mineral beach sands can reach zircon contents of several percent, enabling repeated contact with high-temperature crafts.

A typical industrial sampling scene shows black-and-gold heavy mineral grains collected after wet sieving; furthermore, density separation concentrates zircon-rich fractions above 4.6 g/cm3. Chemical mapping often reveals zircon grains spanning 50–500 µm, while accessory rutile and ilmenite appear as neighboring phases. Therefore, early “natural feedstock” rarely presented as pure zirconium chemistry, but rather as mixed refractory mineral suites.

Subsequently, the mineral-hosted pathway constrained early recognition because zirconia ceramic does not present as a discrete, easily named material in raw sediments.

- Early encounters in ancient metallurgy and glassmaking

High-temperature crafts intermittently used zircon-bearing sands in furnace linings; nevertheless, material selection occurred by trial rather than phase reasoning. In particular, refractory mixes containing zircon-rich grains can tolerate sustained furnace zones above 1200–1500 °C, whereas many clays soften earlier. To demonstrate, repeated firing cycles often left zircon grains visibly intact while surrounding silicate binders vitrified, producing a crude contrast between stable inclusions and flowing matrix.

Workshop observations frequently include vitrified glaze trails around angular grains; meanwhile, the stable grains retain sharp edges after multiple cycles. Particle-size distributions around 100–300 µm promote packing yet still allow binder flow, which affects spallation risk near hot-face surfaces. Hence, early users encountered “durable grains” without vocabulary for zirconia ceramic, solid solution, or polymorphism.

Afterwards, these empirical encounters seeded later hypotheses once analytical chemistry matured enough to isolate oxide composition from mineral behavior.

- Limitations of pre-scientific understanding

Pre-scientific material knowledge lacked crystallographic language; consequently, polymorphism and martensitic-like transformation remained invisible. More importantly, zirconia ceramic cannot be isolated from zircon without high-temperature or chemical routes that exceed ancient processing control. Specifically, conversion of zircon to zirconia and silica requires aggressive thermal decomposition or chemical digestion, while controlled removal of silica demands reagents and filtration discipline.

Archaeometric reconstructions often find refractory fragments with mixed phases; however, phase assemblages vary across millimeters due to local temperature gradients of 50–200 °C during firing. Microcrack patterns can arise from heterogeneous thermal expansion between silicates and zircon-rich grains, which obscures intrinsic zirconia behavior. Ultimately, zirconia ceramic remained an implicit contributor to refractory resilience, yet remained unrecognized as a standalone engineering oxide.

Summary Signals from the Pre-Engineering Era

| Evidence channel | Typical observable | Characteristic scale (µm) | Indicative temperature window (°C) | Primary constraint |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy-mineral concentrates | Zircon-rich grain fraction | 50–500 | 25–200 | Mixed mineral suite |

| Furnace lining remnants | Intact refractory inclusions | 100–300 | 1200–1500 | No phase framework |

| Fired ceramic fragments | Vitrified matrix around stable grains | 10–200 | 900–1400 | Heterogeneous microcracking |

| Early glass batch residues | Persistent high-melting inclusions | 50–250 | 1100–1400 | No oxide isolation route |

Moreover, systematic experimentation revealed that zirconia ceramic failures were not random defects. Instead, recurring cracking patterns exposed a deeper crystallographic mechanism that classical chemistry alone could not explain.

Zirconia Ceramic Phase Behavior and the Tetragonal Problem

Zirconia ceramic entered a decisive turning point once crystallography and thermal analysis matured. Consequently, researchers realized that instability originated from intrinsic phase transformations rather than processing negligence, thereby redefining zirconia as a fundamentally complex oxide system.

Polymorphism of zirconia ceramic

Zirconia ceramic exhibits three primary crystallographic forms: monoclinic, tetragonal, and cubic. Specifically, monoclinic zirconia remains stable below approximately 1170 °C, tetragonal zirconia dominates between roughly 1170 °C and 2370 °C, while the cubic phase appears near the melting region above 2370 °C. These temperature-dependent transitions distinguish zirconia from most engineering oxides.

Experimental dilatometry traces show abrupt dimensional changes during cooling; notably, the tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation introduces a volumetric expansion approaching 3–5%. In controlled furnace trials, cooling rates as low as 2–5 °C per minute still triggered spontaneous cracking once the transformation temperature was crossed. Therefore, zirconia ceramic bodies fractured even under gentle thermal schedules.

As a result, zirconia ceramic could not be treated as a single-phase material. Instead, its behavior depended on thermal history, grain size, and constraint conditions, complicating every attempt at densification and shaping.

Catastrophic cracking during cooling

Thermal cycling experiments repeatedly demonstrated that zirconia ceramic failure occurred during cooling rather than firing. In particular, specimens appeared intact at peak temperatures yet disintegrated upon furnace exit. This observation contradicted prevailing ceramic intuition, which associated cracking primarily with insufficient sintering.

Microscopic examination reveals radial and intergranular crack networks originating at transformed grains. Furthermore, acoustic emission monitoring detects sudden energy release precisely within the 900–1100 °C window, corresponding to the monoclinic reversion. Quantitatively, fracture events cluster within seconds after crossing the transformation threshold, regardless of specimen geometry.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic earned a reputation as “self-destructive,” since fracture arose internally without external loading. This perception stalled adoption and discouraged further mechanical testing for several decades.

Why zirconia ceramic was once considered unusable

Compared with alumina or magnesia, zirconia ceramic violated the assumption of dimensional stability. Whereas alumina contracts smoothly upon cooling, zirconia expands abruptly during phase reversal. This behavior rendered standard ceramic design rules ineffective.

Mechanical testing further reinforced skepticism. Flexural strength values rarely exceeded 150–200 MPa in early dense specimens, while scatter remained extreme. Moreover, fracture surfaces displayed transformation-induced microcracking rather than flaw-controlled failure, undermining conventional strength models.

Ultimately, zirconia ceramic was classified as a scientific curiosity rather than a structural material. Nevertheless, this classification masked an important insight: the very transformation causing failure also stored latent toughening potential, which would later redefine ceramic mechanics.

Summary of Phase-Related Barriers in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Phase form | Stability temperature range (°C) | Volume change at transition (%) | Engineering consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclinic | <1170 | Reference state | Stable at ambient conditions |

| Tetragonal | 1170–2370 | +3–5 on cooling | Crack initiation risk |

| Cubic | >2370 | Minimal | High-temperature stability |

| Unstabilized body | Cooling through 900–1100 | Sudden expansion | Catastrophic fracture |

| Early dense specimens | Ambient testing | Microcrack networks | Low strength reliability |

Furthermore, repeated failure forced a conceptual shift away from processing optimization toward compositional intervention. Consequently, zirconia ceramic entered an era where chemistry was deliberately used to restrain crystallographic instability rather than merely endure it.

Stabilized Zirconia Ceramic and the Birth of Composition Engineering

Zirconia ceramic stabilization marked a fundamental transition from descriptive materials science to intentional composition engineering. Instead of avoiding phase transformation, researchers learned to control it through targeted dopant incorporation, thereby converting instability into a manageable design variable.

Discovery of oxide stabilizers

The first stabilization strategies emerged when alkaline and rare-earth oxides were introduced into zirconia ceramic lattices. Specifically, additions of yttria (Y₂O₃), calcia (CaO), magnesia (MgO), and later ceria (CeO₂) altered oxygen vacancy concentration and lattice symmetry. These dopants substituted into zirconium sites or created charge-compensating defects, suppressing the monoclinic phase at ambient temperature.

Quantitative phase diagrams2 revealed that 3–5 mol% Y₂O₃ could retain the tetragonal phase metastably at room conditions, while higher dopant levels above 8 mol% promoted a fully cubic structure. As a result, phase transformation temperatures shifted downward by several hundred degrees Celsius. Dilatometric measurements confirmed that volumetric expansion during cooling could be reduced from 3–5% to below 0.3%, dramatically improving dimensional integrity.

Accordingly, zirconia ceramic ceased to be intrinsically unstable. Instead, stability became a function of dopant type, concentration, and distribution, inaugurating a new materials design philosophy.

Partially stabilized zirconia ceramic systems

Partially stabilized zirconia ceramic systems represented a compromise between phase stability and mechanical performance. Rather than eliminating tetragonal zirconia entirely, these compositions preserved finely dispersed tetragonal precipitates within a cubic or constrained matrix. This architecture limited spontaneous transformation while maintaining transformation capability under stress.

Microstructural analysis shows tetragonal grain sizes typically controlled below 0.5 µm, embedded within cubic grains exceeding 1–3 µm. Such configurations allowed stress-induced transformation without bulk expansion. Mechanical testing demonstrated flexural strength improvements to 400–600 MPa, alongside fracture toughness values approaching 6–8 MPa·m¹ᐟ².

Nevertheless, partial stabilization introduced sensitivity to grain growth and dopant segregation. Consequently, sintering temperature windows narrowed to within ±50 °C, requiring stricter thermal discipline. This trade-off highlighted that zirconia ceramic performance depended equally on composition and microstructural control.

Trade-offs introduced by stabilization

While stabilization solved catastrophic cracking, it introduced new engineering constraints. Increased oxygen vacancy concentration enhanced ionic mobility, which benefited functional applications but reduced resistance to hydrothermal environments. In particular, low-temperature degradation3 became observable in humid atmospheres below 300 °C for certain yttria-stabilized systems.

Thermomechanical testing further revealed that fully cubic zirconia ceramic, although dimensionally stable, exhibited lower fracture toughness, typically below 3 MPa·m¹ᐟ². Conversely, lightly stabilized compositions risked spontaneous aging if grain sizes exceeded critical thresholds. Therefore, stabilization was not a universal remedy but a balancing act among competing properties.

Ultimately, stabilization reframed zirconia ceramic as a tunable material platform. Instead of asking whether zirconia could survive processing, engineers began selecting compositions to match stress state, temperature exposure, and environmental chemistry.

Summary of Stabilization Strategies in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Stabilizer oxide | Typical content (mol%) | Retained phase at room temperature | Volume change on cooling (%) | Representative toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y₂O₃ | 3–5 | Metastable tetragonal | <0.3 | 6–8 |

| Y₂O₃ | ≥8 | Cubic | ~0 | 2–3 |

| CaO | 8–12 | Cubic | ~0 | 2–3 |

| MgO | 8–10 | Cubic | ~0 | 2–3 |

| CeO₂ | 10–16 | Tetragonal / cubic | <0.5 | 7–9 |

| Unstabilized | 0 | Monoclinic | 3–5 | <2 |

Additionally, the stabilization era uncovered an unexpected mechanical phenomenon. Instead of merely suppressing failure, zirconia ceramic began to exhibit a self-reinforcing response under stress, thereby overturning long-held assumptions about ceramic brittleness.

Transformation Toughening and the Reinvention of Zirconia Ceramic

Transformation toughening redefined zirconia ceramic from a stabilized refractory into a mechanically competitive material. Consequently, phase transformation shifted from a liability into a controllable energy-dissipation mechanism, establishing zirconia as a cornerstone of advanced structural ceramics.

Stress induced phase transformation

Transformation toughening arises when metastable tetragonal zirconia grains undergo a stress-triggered transformation to the monoclinic phase. Specifically, tensile stress concentrated at a crack tip initiates this transformation locally, producing a volumetric expansion of approximately 3–5% confined to the crack vicinity. This expansion generates compressive stresses that oppose crack propagation.

High-resolution fracture analysis consistently shows transformed monoclinic zones extending 0.5–2 µm ahead of advancing cracks. Moreover, in situ loading experiments demonstrate that crack growth rates can decrease by more than an order of magnitude once transformation initiates. As a result, zirconia ceramic absorbs fracture energy internally rather than releasing it catastrophically.

Therefore, the same phase change once responsible for spontaneous fracture became a protective mechanism when spatially constrained and compositionally controlled.

Fracture mechanics revolution

The impact of transformation toughening on ceramic mechanics was profound. Fracture toughness values for yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystals (Y-TZP) routinely reached 7–10 MPa·m¹ᐟ², surpassing alumina by a factor of three. Flexural strength concurrently increased to 800–1200 MPa in fine-grained bodies.

Mechanical testing campaigns revealed R-curve behavior, wherein resistance to crack growth rises with increasing crack length. This response contrasts sharply with traditional ceramics, which exhibit flat R-curves and brittle failure. Furthermore, cyclic fatigue tests showed endurance limits exceeding 50% of monotonic strength after 10⁶ loading cycles.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic disrupted the classical boundary between brittle ceramics and ductile metals, enabling load-bearing roles previously considered unattainable for oxide ceramics.

Limits and sensitivity of transformation toughening

Despite its advantages, transformation toughening imposes strict microstructural constraints. Grain size must remain below a critical threshold, typically 0.3–0.6 µm for Y-TZP, to prevent spontaneous transformation during cooling or aging. Exceeding this limit destabilizes the tetragonal phase even in the absence of stress.

Environmental exposure further complicates performance. In humid conditions below 300 °C, hydrothermal aging can trigger gradual surface transformation, reducing strength by 20–40% over extended periods. Additionally, excessive stabilizer content suppresses transformation entirely, diminishing toughness to levels comparable with conventional ceramics.

Accordingly, transformation toughening represents a conditional advantage rather than an inherent guarantee. Zirconia ceramic performance depends on precise alignment of composition, grain size, and service environment.

Summary of Transformation Toughening Parameters in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Parameter | Typical range | Quantified effect | Engineering implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetragonal grain size (µm) | 0.2–0.6 | Stable metastability | Enables stress-induced transformation |

| Local volume expansion (%) | 3–5 | Crack tip compression | Crack arrest mechanism |

| Fracture toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | 7–10 | 3× alumina | Structural load capability |

| Flexural strength (MPa) | 800–1200 | High reliability | Precision components |

| Aging strength loss (%) | 20–40 | Environmental sensitivity | Surface engineering required |

Moreover, mechanical breakthroughs alone did not guarantee reliable components. Consequently, zirconia ceramic required a parallel evolution in processing science, where powder chemistry, forming discipline, and sintering kinetics collectively determined whether theoretical properties could be realized in practice.

Zirconia Ceramic Processing Science from Powder to Dense Bodies

Zirconia ceramic processing matured once engineers recognized that phase control depends on microstructural precision. Accordingly, powder synthesis, shaping routes, and thermal schedules became inseparable variables rather than isolated steps.

Powder synthesis routes

Zirconia ceramic performance begins at the powder scale, where chemistry dictates defect distribution and grain evolution. Co-precipitation methods produce chemically homogeneous powders with primary particle sizes typically between 10 and 30 nm, enabling uniform stabilizer dispersion. By contrast, mechanically milled powders often exceed 1 µm, introducing compositional gradients that later manifest as weak zones.

Hydrothermal synthesis further refined powder quality by crystallizing zirconia at temperatures below 300 °C under autogenous pressure. This approach yields narrow particle size distributions around 20–50 nm and reduces agglomeration forces. Consequently, sintering onset temperatures can drop by 150–250 °C compared with coarse powders.

Experimental processing records frequently note that powders with specific surface areas above 12–15 m²/g achieve near-full density without exaggerated grain growth. Therefore, powder synthesis represents the first decisive control point in zirconia ceramic evolution.

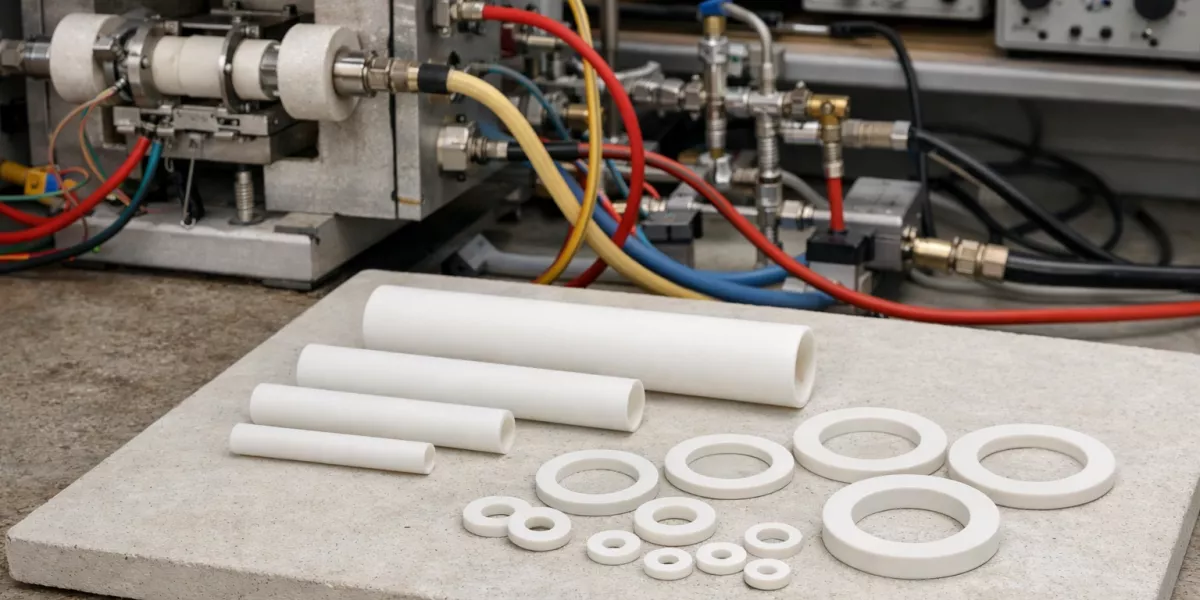

Forming methods for zirconia ceramic

Shaping techniques translate powder quality into macroscopic geometry while preserving microstructural uniformity. Uniaxial pressing remains suitable for simple geometries; however, density gradients of 3–6% across thick sections are common. Such gradients amplify stress concentration during sintering.

Cold isostatic pressing reduces these variations to below 1–2%, enabling thicker components with consistent shrinkage. Meanwhile, ceramic injection molding supports complex shapes with tolerances below ±0.2%, provided binder burnout proceeds uniformly. Field experience consistently shows that incomplete debinding above 400 °C leads to internal porosity exceeding 2 vol%, compromising strength.

Green machining further improves dimensional control by allowing material removal before densification. As a result, zirconia ceramic components achieve tighter tolerances with reduced post-sintering grinding, limiting surface damage accumulation.

Sintering kinetics and grain control

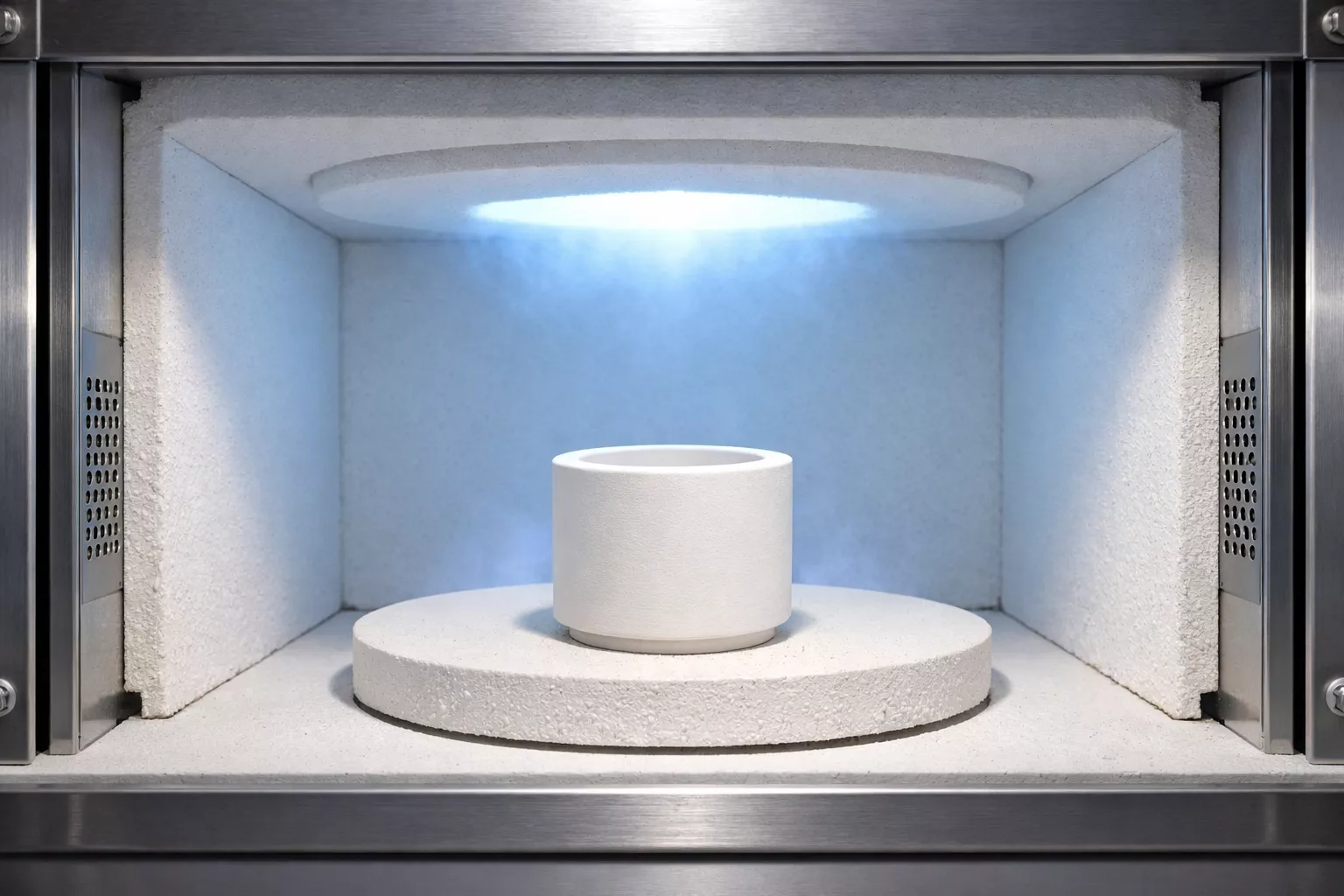

Sintering transforms shaped bodies into load-bearing zirconia ceramic through diffusion-driven densification. Conventional pressureless sintering typically requires peak temperatures of 1350–1500 °C for fine powders, achieving relative densities above 99%. However, excessive dwell times promote grain growth beyond critical stability thresholds.

Hot isostatic pressing introduces external pressure of 100–200 MPa at 1200–1400 °C, closing residual porosity below 0.1%. This technique enhances strength reproducibility, particularly for safety-critical components. Nevertheless, HIP processing demands precise encapsulation to prevent surface contamination.

Grain growth kinetics follow a power-law relationship with temperature and time. Empirical data indicate that maintaining average grain sizes below 0.5 µm preserves tetragonal stability, whereas growth beyond 0.8 µm increases spontaneous transformation risk. Therefore, sintering schedules must balance densification and phase retention simultaneously.

Summary of Processing Parameters Governing Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Processing stage | Typical parameter | Quantified range | Structural outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powder particle size (nm) | Primary crystallite | 10–50 | Enhanced sinterability |

| Specific surface area (m²/g) | Powder reactivity | 12–20 | Lower sintering temperature |

| Forming density variation (%) | Green body uniformity | <2 | Reduced internal stress |

| Sintering temperature (°C) | Pressureless | 1350–1500 | >99% relative density |

| HIP pressure (MPa) | Post-sinter densification | 100–200 | Porosity <0.1% |

| Average grain size (µm) | Post-sinter | 0.3–0.6 | Phase stability retention |

Likewise, once processing reliability converged with transformation toughening, zirconia ceramic transitioned from laboratory specimens to load-bearing hardware. Consequently, mechanical engineers began evaluating zirconia not as a brittle oxide, but as a structural material with predictable fatigue and wear behavior.

Structural Zirconia Ceramic in Mechanical Engineering Systems

Structural deployment marked the moment when zirconia ceramic entered real mechanical duty. Instead of serving as a passive refractory, it began carrying load, resisting wear, and maintaining geometry under cyclic stress, thereby redefining expectations for oxide ceramics.

Wear resistance and strength retention

Zirconia ceramic demonstrates exceptional resistance to sliding and abrasive wear due to its high hardness and transformation-assisted surface stability. Vickers hardness values typically range from 1200 to 1400 HV for Y-TZP, while contact-induced phase transformation locally increases compressive stress at wear interfaces. This mechanism suppresses micro-fracture during repeated sliding.

Pin-on-disk testing frequently reports wear rates below 1 × 10⁻⁶ mm³/N·m against hardened steel counterparts, even under contact stresses exceeding 1 GPa. Moreover, surface roughness remains stable below Ra 0.05 µm after extended operation, indicating limited grain pull-out. As a result, zirconia ceramic shafts, pins, and bearing sleeves maintain dimensional fidelity across long service intervals.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic displaced alumina in applications where surface degradation directly affected precision or seal integrity.

Fatigue behavior under cyclic loading

Cyclic fatigue once represented a critical uncertainty for ceramics. However, zirconia ceramic exhibits atypical endurance behavior due to transformation toughening and crack-tip shielding. Four-point bending fatigue tests demonstrate endurance limits between 400 and 600 MPa after 10⁶ cycles, corresponding to approximately 50–60% of monotonic flexural strength.

Crack initiation under cyclic load occurs later than in conventional ceramics because stress-induced transformation reduces crack-tip stress intensity. Additionally, microcrack accumulation remains localized rather than catastrophic, delaying unstable fracture. Acoustic emission monitoring confirms gradual energy dissipation rather than sudden failure events.

Therefore, zirconia ceramic became viable for rotating and reciprocating components where cyclic stress dominates over static load.

Comparison with silicon nitride and alumina

Material selection among advanced ceramics requires contextual comparison. Alumina offers high stiffness and chemical stability, yet fracture toughness rarely exceeds 4 MPa·m¹ᐟ², limiting impact tolerance. Silicon nitride provides superior thermal shock resistance and comparable toughness, typically 6–8 MPa·m¹ᐟ², but demands complex sintering aids and higher processing costs.

Zirconia ceramic occupies an intermediate position. Its fracture toughness of 7–10 MPa·m¹ᐟ² and flexural strength approaching 1200 MPa enable compact designs under high stress. However, thermal conductivity remains lower, commonly 2–3 W/m·K, which restricts use in heat-dissipative roles.

Accordingly, zirconia ceramic is preferentially selected where wear resistance, strength retention, and geometric stability outweigh thermal transport requirements.

Summary of Structural Performance Metrics in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Property | Zirconia ceramic | Alumina ceramic | Silicon nitride ceramic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexural strength (MPa) | 800–1200 | 300–500 | 700–1000 |

| Fracture toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | 7–10 | 3–4 | 6–8 |

| Wear rate (mm³/N·m) | <1 × 10⁻⁶ | ~1 × 10⁻⁵ | ~5 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Fatigue endurance (% of σₘ) | 50–60 | 30–40 | 50–55 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) | 2–3 | 20–30 | 20–35 |

Similarly, as confidence in mechanical reliability increased, zirconia ceramic crossed an unusual boundary between machines and the human body. Consequently, material science priorities shifted toward purity, surface stability, and long-term interaction with biological environments.

Zirconia Ceramic in Biomedical and Human-Interface Applications

Zirconia ceramic adoption in biomedical contexts emerged from its combination of strength and chemical neutrality. Moreover, the same phase-control principles developed for structural components proved essential for ensuring safety and durability when zirconia interfaces directly with human tissue.

Biocompatibility foundations

Zirconia ceramic exhibits exceptional biological inertness because zirconium ions remain strongly bound within the oxide lattice. In vitro cytotoxicity assays consistently report cell viability above 95% after 72-hour exposure, exceeding thresholds required for implantable materials. Furthermore, ionic release measurements typically remain below 0.01 mg/L under simulated physiological conditions.

Surface chemistry plays a decisive role in tissue response. Polished zirconia ceramic surfaces with roughness below Ra 0.05 µm minimize protein denaturation, while moderately roughened surfaces around Ra 0.5–1.0 µm promote osteointegration. Accordingly, surface preparation became a controllable biological variable rather than a purely aesthetic choice.

As a result, zirconia ceramic achieved acceptance as a bioinert structural material rather than merely a coating or filler.

Dental and orthopedic zirconia ceramic

Dental applications rapidly adopted yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystals due to their high fracture resistance under mastication loads. Typical bite forces generate localized stresses approaching 300–600 MPa; however, Y-TZP crowns and bridges routinely tolerate these loads with safety factors above 2. Flexural strength values near 900–1200 MPa provide sufficient margin against chipping and catastrophic fracture.

Orthopedic uses followed a more cautious trajectory. Femoral heads manufactured from zirconia ceramic exhibit low wear rates against ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene, often below 1 mm³ per million cycles. Nevertheless, early generations experienced unexpected degradation linked to phase instability, highlighting the sensitivity of zirconia ceramic to service environment.

Thus, biomedical success depended not only on bulk strength but also on long-term phase stability under physiological conditions.

Lessons from in-vivo degradation

Clinical observations revealed that hydrothermal aging could occur within the human body, where temperatures near 37 °C and continuous moisture exposure persist. In certain zirconia ceramic formulations, surface tetragonal grains gradually transformed to the monoclinic phase, inducing roughening and microcrack formation. Quantitatively, monoclinic phase fractions increased from below 5% to over 25% after several years in vivo for inadequately stabilized materials.

Mechanical consequences followed surface degradation. Strength reductions of 20–40% were reported in retrieved implants, accompanied by increased wear debris generation. Consequently, stabilizer content, grain size distribution, and surface finishing protocols were reevaluated across the biomedical sector.

Ultimately, these lessons reinforced a central theme of Zirconia Ceramic Evolution: performance emerges from long-term phase equilibrium rather than initial mechanical metrics alone.

Summary of Biomedical Performance Parameters in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Parameter | Typical value | Test or observation condition | Clinical implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell viability (%) | >95 | 72 h in vitro assay | Biocompatibility |

| Ionic release (mg/L) | <0.01 | Simulated body fluid | Chemical inertness |

| Flexural strength (MPa) | 900–1200 | Dental-grade Y-TZP | Load-bearing safety |

| Wear rate (mm³/10⁶ cycles) | <1 | Hip joint simulation | Reduced debris |

| Monoclinic phase increase (%) | <5 to >25 | Long-term implantation | Aging sensitivity |

| Strength reduction (%) | 20–40 | Retrieved implant analysis | Design revision trigger |

Meanwhile, mechanical credibility opened a pathway toward functional deployment. Consequently, zirconia ceramic expanded beyond load-bearing roles into energy systems where ionic transport and thermal endurance dominate performance criteria.

Zirconia Ceramic as a Functional Material in Energy Systems

Zirconia ceramic occupies a unique position among oxides by combining structural stability with oxygen ion mobility. Accordingly, energy technologies leveraged defect chemistry rather than fracture mechanics, shifting emphasis from toughness toward conductivity and long-term thermochemical balance.

Oxygen ion conductivity

Cubic zirconia ceramic exhibits high oxygen ion conductivity due to oxygen vacancies introduced by aliovalent dopants. Specifically, stabilizers such as yttria create vacancy concentrations proportional to dopant level, enabling oxide-ion diffusion through the lattice. Conductivity values typically reach 0.1–0.2 S/cm at 1000 °C for 8 mol% yttria-stabilized zirconia.

Impedance spectroscopy reveals Arrhenius behavior with activation energies around 0.9–1.1 eV, reflecting vacancy migration barriers. Moreover, grain boundary resistance can account for up to 30–40% of total impedance in fine-grained ceramics, particularly below 800 °C. Therefore, microstructural refinement directly influences functional efficiency.

As a consequence, zirconia ceramic design for energy systems prioritizes vacancy distribution uniformity and grain boundary cleanliness rather than transformation toughening.

Solid oxide fuel cells and sensors

Solid oxide fuel cells rely on zirconia ceramic electrolytes to transport oxygen ions while blocking electronic conduction. Typical electrolyte thicknesses range from 5 to 200 µm, with thinner layers reducing ohmic loss but increasing processing complexity. At operating temperatures of 700–1000 °C, stabilized zirconia maintains chemical stability against hydrogen, oxygen, and mixed gas atmospheres.

Electrochemical sensors similarly exploit oxygen ion conductivity to measure partial pressure differentials. Response times below 1 second are commonly achieved at temperatures above 600 °C, while measurement accuracy remains within ±1–2% across wide oxygen concentration ranges. These attributes derive from zirconia ceramic’s stable defect structure under fluctuating redox conditions.

Thus, zirconia ceramic evolved into a functional backbone of high-temperature electrochemical systems rather than merely a supporting structure.

Stability challenges in long-term operation

Despite functional advantages, long-term operation introduces degradation pathways distinct from mechanical aging. Grain boundary segregation of dopants can reduce ionic conductivity by 10–30% after thousands of hours at elevated temperature. Additionally, thermal cycling between ambient and operating temperatures induces microcrack formation if thermal expansion mismatch exists with adjacent electrodes.

Redox cycling further complicates stability. Repeated exposure to reducing atmospheres can alter local oxygen vacancy distribution, affecting both conductivity and mechanical integrity. Empirical endurance tests indicate that conductivity loss rates below 1% per 1000 hours are achievable only when impurity levels remain under 0.1 wt%.

Accordingly, functional zirconia ceramic performance depends on chemical purity, dopant homogeneity, and interface engineering as much as intrinsic conductivity.

Summary of Functional Performance Metrics in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Functional parameter | Typical range | Operating condition | System-level implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen ion conductivity (S/cm) | 0.1–0.2 | 1000 °C | Efficient ion transport |

| Activation energy (eV) | 0.9–1.1 | Arrhenius regime | Vacancy mobility |

| Grain boundary impedance (%) | 30–40 | <800 °C | Microstructure sensitivity |

| Electrolyte thickness (µm) | 5–200 | SOFC stacks | Ohmic loss control |

| Sensor response time (s) | <1 | >600 °C | Rapid signal accuracy |

| Conductivity degradation (%/1000 h) | <1–30 | Long-term operation | Lifetime limitation |

Additionally, as single-phase optimization approached physical limits, zirconia ceramic development shifted toward composite architectures. Consequently, hybridization emerged as a strategy to reconcile competing requirements that no monolithic ceramic could satisfy simultaneously.

Advanced Zirconia Ceramic Composites and Hybrid Systems

Zirconia ceramic composites extend performance boundaries by integrating complementary phases at controlled length scales. Moreover, composite design reframes zirconia from a standalone solution into a tunable constituent within multiphase systems engineered for stress redistribution, thermal compatibility, and damage tolerance.

Zirconia-toughened alumina

Zirconia-toughened alumina combines the stiffness and thermal conductivity of alumina with the transformation toughening of zirconia ceramic. Typically, 10–25 vol% tetragonal zirconia particles are dispersed within an alumina matrix, with zirconia grain sizes constrained below 0.5 µm to preserve metastability. This architecture introduces localized transformation near crack tips while maintaining a rigid load-bearing framework.

Mechanical testing shows flexural strength values of 600–900 MPa and fracture toughness between 6 and 8 MPa·m¹ᐟ², exceeding monolithic alumina by more than 100%. Additionally, elastic modulus remains high, commonly 300–380 GPa, which improves dimensional stability under load. Wear experiments indicate rates below 5 × 10⁻⁶ mm³/N·m in dry sliding, reflecting synergistic surface behavior.

Accordingly, zirconia-toughened alumina became favored where stiffness and wear resistance are critical, yet catastrophic fracture must be avoided.

Functionally graded zirconia ceramic

Functionally graded zirconia ceramic systems address thermal and mechanical mismatches by spatially varying composition. In particular, zirconia content is increased near surfaces exposed to impact or wear, while alumina-rich or zirconia-lean regions occupy the core to control expansion and stiffness gradients. Gradient thicknesses typically range from 0.5 to 3 mm depending on component scale.

Thermomechanical simulations correlate graded profiles with reduced interfacial stress by 20–40% under thermal gradients exceeding 500 °C. Experimental bending tests confirm delayed crack initiation and more stable crack paths compared with abrupt interfaces. Furthermore, graded structures mitigate delamination risks common in layered ceramics.

Thus, functional grading transforms zirconia ceramic from a uniform material into a spatially optimized system aligned with service stress fields.

Multi-phase hybridization limits and controls

Composite benefits depend on precise interphase control. Excessive zirconia content can lower thermal conductivity to below 6 W/m·K in ZTA systems, while insufficient constraint permits premature transformation. Grain-boundary chemistry must also be managed, as impurity segregation above 0.2 wt% can weaken interfaces and accelerate aging.

Processing routes such as tape casting, slurry infiltration, and co-sintering demand synchronized shrinkage within ±1% to avoid residual stress. In practice, successful hybrids exhibit residual stress levels below 50 MPa after cooling, preserving long-term integrity.

Ultimately, composite zirconia ceramic systems demonstrate that performance gains arise from architectural design as much as intrinsic material properties.

Summary of Composite Strategies in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Composite system | Zirconia content (vol%) | Fracture toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | Flexural strength (MPa) | Key advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monolithic zirconia ceramic | 100 | 7–10 | 800–1200 | High toughness |

| Zirconia-toughened alumina | 10–25 | 6–8 | 600–900 | Stiffness–toughness balance |

| Alumina matrix composite | <10 | 4–6 | 500–700 | Thermal stability |

| Functionally graded ceramic | Spatially varied | 6–9 | 600–1000 | Stress redistribution |

| Layered hybrid systems | Variable | 5–8 | 550–950 | Interface tailoring |

Nevertheless, progress in zirconia ceramic performance never followed a linear ascent. Instead, each advance exposed new failure modes, thereby forcing iterative reassessment of assumptions that once appeared settled.

Manufacturing Bottlenecks and Failure Lessons in Zirconia Ceramic History

Zirconia ceramic evolution has been shaped as much by failure as by success. Accordingly, manufacturing bottlenecks and in-service breakdowns repeatedly redirected formulation strategies, processing discipline, and qualification criteria across industries.

Processing induced defects

Manufacturing-related defects represent the earliest and most persistent limitation in zirconia ceramic deployment. In particular, residual porosity, agglomerate retention, and density gradients originate during powder handling and forming stages. Even when average density exceeds 99%, isolated pores larger than 5–10 µm can dominate fracture behavior.

Fractographic analysis consistently links critical flaws to incomplete binder removal or powder agglomerates exceeding 20 µm in size. Such defects amplify local stress intensity by factors of 2–3 under bending loads. Moreover, thermal gradients during sintering can introduce residual stresses exceeding 80–120 MPa, sufficient to activate premature transformation or microcracking.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic reliability became inseparable from statistical process control4, emphasizing defect population rather than nominal material properties.

Aging failures and unexpected degradation

Beyond fabrication, time-dependent degradation emerged as a defining challenge. Low-temperature degradation in humid environments revealed that metastable tetragonal zirconia can slowly transform without applied stress. Surface layers as thin as 20–50 µm may accumulate monoclinic content exceeding 30% after prolonged exposure below 300 °C.

Mechanical repercussions follow gradually rather than abruptly. Strength measurements often decline by 1–2% per month under accelerated aging protocols, while surface roughness increases from Ra 0.05 µm to above 0.3 µm. These changes alter contact mechanics and promote debris formation in dynamic systems.

Thus, aging failures demonstrated that zirconia ceramic evolution must consider service duration and environment, not merely initial qualification data.

How each failure reshaped formulation strategies

Each identified failure mechanism triggered corrective reformulation. Grain size limits were tightened to below 0.5 µm to suppress spontaneous transformation, while stabilizer distributions were homogenized to within ±0.2 mol%. Additionally, secondary dopants such as alumina at levels of 0.1–0.3 wt% were introduced to inhibit grain boundary mobility.

Processing routes adapted accordingly. Sintering windows narrowed, impurity thresholds dropped below 0.05 wt%, and surface finishing protocols emphasized compressive residual stress induction. These changes reduced strength scatter by more than 40% in statistically significant production runs.

Ultimately, failure analysis transformed zirconia ceramic from a nominally tough material into a rigorously engineered system whose reliability derives from disciplined control at every scale.

Summary of Failure Driven Corrections in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Failure category | Quantified symptom | Root cause | Implemented correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residual porosity | Pores >10 µm | Agglomerates | Powder deagglomeration |

| Residual stress (MPa) | 80–120 | Thermal gradients | Optimized sintering ramps |

| Aging transformation (%) | >30 monoclinic | Humidity exposure | Grain size refinement |

| Strength loss (%) | 20–40 | Surface degradation | Dopant redistribution |

| Property scatter (%) | >50 variation | Process inconsistency | Statistical control |

Subsequently, once manufacturing discipline stabilized performance, zirconia ceramic diffused across multiple industrial domains. Accordingly, application diversity reflected accumulated confidence rather than isolated experimentation.

Zirconia Ceramic Across Industrial Sectors

Zirconia ceramic penetrated industry through parallel adoption rather than a single dominant pathway. Moreover, sector-specific demands selectively emphasized strength, chemical stability, or functional response, demonstrating the material’s adaptability across engineered systems.

- Metallurgy and high-temperature handling

Zirconia ceramic components appear in molten metal handling where thermal shock and chemical resistance coexist. Typical service temperatures exceed 1400 °C, while contact with aggressive slags demands low wettability and structural integrity. As a result, zirconia ceramic nozzles and liners retain geometry longer than alumina counterparts.

Repeated casting cycles show dimensional drift below 0.2% after 100 thermal cycles, which supports process repeatability. Furthermore, resistance to metal penetration reduces contamination risk in precision alloys. Therefore, zirconia ceramic contributes indirectly to metallurgical yield stability.

- Chemical processing and corrosion environments

Chemical systems exploit zirconia ceramic for its resistance to acids and alkalis across broad temperature ranges. Unlike silica-based ceramics, zirconia remains stable in both oxidizing and reducing media. Consequently, components such as valve seats and pump elements exhibit extended service life.

Field data indicate mass loss rates below 0.01 mg/cm² after 100-hour immersion tests in concentrated alkaline solutions. Moreover, smooth surface retention limits fouling accumulation. Thus, zirconia ceramic addresses durability challenges in corrosive flow systems.

- Electronics and precision equipment

In electronics, zirconia ceramic functions as a mechanically robust insulator rather than a thermal conductor. Dielectric constants around 25–30 enable compact geometries, while dielectric loss remains low at elevated frequencies. Additionally, high flexural strength supports thin-wall designs without fracture risk.

Precision positioning stages and measuring fixtures utilize zirconia ceramic for dimensional stability. Thermal expansion coefficients near 10 × 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹ permit predictable compensation strategies. Hence, zirconia ceramic supports accuracy rather than speed in precision assemblies.

- Industrial wear and motion control

Wear-intensive sectors deploy zirconia ceramic in bearings, guides, and sealing interfaces. High hardness combined with transformation-assisted surface stability limits abrasive damage. Consequently, operational lifetimes often double relative to hardened steel in dry or marginally lubricated conditions.

Tribological testing shows friction coefficients around 0.3–0.4 against steel under dry sliding. Furthermore, absence of adhesive wear reduces debris-induced secondary damage. Therefore, zirconia ceramic enhances reliability in continuous-motion systems.

Summary of Sector-Specific Adoption in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Industrial sector | Dominant property | Typical service condition | Performance indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallurgy | Thermal stability | >1400 °C cycling | <0.2% dimensional change |

| Chemical processing | Corrosion resistance | Acidic and alkaline media | <0.01 mg/cm² mass loss |

| Electronics | Electrical insulation | High frequency fields | Stable dielectric response |

| Precision equipment | Dimensional stability | Thermal fluctuation | Predictable expansion |

| Wear systems | Abrasion resistance | Sliding contact | Extended service life |

Ultimately, after centuries of refinement driven by failure and correction, zirconia ceramic research has shifted toward predictive control. Consequently, contemporary work focuses less on discovering new phenomena and more on mastering complexity through scale-sensitive design.

Scientific Frontiers of Zirconia Ceramic Research

Zirconia ceramic research now operates at the intersection of materials physics, data-driven modeling, and nanoscale engineering. Moreover, future progress depends on controlling variability rather than increasing nominal property values.

Nanostructured zirconia ceramic

Nanostructuring represents a decisive frontier in zirconia ceramic evolution. By reducing grain sizes into the 50–200 nm regime, metastable tetragonal retention becomes more robust even at reduced stabilizer concentrations. This approach decreases oxygen vacancy clustering and delays spontaneous transformation.

Experimental sintering studies demonstrate that nanostructured zirconia ceramic can maintain fracture toughness above 8 MPa·m¹ᐟ² while reducing stabilizer content by nearly 30%. Additionally, grain-boundary area increases significantly, which alters diffusion pathways and suppresses abnormal grain growth. However, excessive boundary density raises sensitivity to impurity segregation above 0.02 wt%.

Accordingly, nanostructured zirconia ceramic demands ultra-clean processing environments and precise thermal schedules to realize theoretical advantages.

Dopant chemistry refinement

Beyond single-stabilizer systems, multi-dopant strategies refine defect chemistry with greater precision. Co-doping with yttria and ceria, for example, balances phase stability with resistance to hydrothermal aging. Quantitative phase analysis indicates monoclinic phase formation below 5% even after accelerated aging equivalent to 20 years of service.

Defect modeling reveals that mixed dopants distribute oxygen vacancies more uniformly, lowering local stress concentrations. Mechanical testing confirms strength retention above 85% of initial values after long-term exposure. Moreover, thermal conductivity can be tuned between 2 and 4 W/m·K through dopant selection.

Thus, dopant chemistry has evolved from stabilization toward fine-scale property modulation.

Predictive modeling and digital materials science

Digital tools increasingly guide zirconia ceramic design by predicting phase behavior and lifetime performance. Phase-field simulations capture transformation kinetics at crack tips, correlating local stress intensity with grain size and dopant concentration. These models reduce experimental iteration cycles by narrowing viable composition windows.

Machine-learning frameworks trained on processing datasets identify correlations between sintering profiles and defect populations. In controlled studies, predictive optimization reduced strength variability by more than 35% across production batches. Furthermore, digital twins simulate service aging, forecasting conductivity loss or toughness degradation under defined environments.

Consequently, zirconia ceramic evolution now integrates computation as a co-equal partner to experimental science.

Summary of Emerging Research Directions in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Research direction | Key parameter | Quantified target | Anticipated impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanostructuring | Grain size (nm) | 50–200 | Enhanced phase stability |

| Multi-dopant systems | Monoclinic fraction (%) | <5 | Aging resistance |

| Vacancy distribution | Defect uniformity | High homogeneity | Property predictability |

| Modeling accuracy | Strength scatter reduction (%) | >35 | Manufacturing reliability |

| Digital lifetime prediction | Degradation error (%) | <10 | Service assurance |

In the final analysis, the historical trajectory of zirconia ceramic reveals a rare convergence of scientific persistence and engineering discipline. Consequently, its enduring relevance stems from lessons accumulated across chemistry, mechanics, and long-term service behavior.

Why Zirconia Ceramic Remains a Cornerstone Material

Zirconia ceramic persists as a cornerstone material because it embodies controlled complexity rather than isolated excellence. Moreover, its evolution demonstrates how apparent weaknesses can be reinterpreted as functional advantages through informed design.

The defining characteristic of zirconia ceramic lies in its managed phase instability. Instead of eliminating transformation behavior, material scientists learned to constrain and activate it selectively. This principle enabled fracture toughness levels between 7 and 10 MPa·m¹ᐟ² while preserving flexural strength approaching 1200 MPa. Consequently, zirconia ceramic occupies a mechanical niche once thought exclusive to metals.

Equally important, zirconia ceramic exemplifies the transition from material discovery to systems engineering. Powder synthesis, dopant chemistry, microstructural control, and surface engineering collectively determine performance. Industrial experience shows that when grain size remains below 0.6 µm and impurity levels fall under 0.05 wt%, property scatter narrows by more than 40%. Thus, reliability emerges from disciplined integration rather than isolated optimization.

Finally, zirconia ceramic continues to adapt as application boundaries expand. Structural components exploit transformation toughening, biomedical systems demand aging resistance, and energy devices rely on ionic conductivity. This versatility arises not from universality, but from tunability. Therefore, zirconia ceramic remains indispensable precisely because it can be engineered to serve divergent, demanding environments without abandoning its fundamental oxide nature.

Summary of Enduring Attributes in Zirconia Ceramic Evolution

| Attribute | Quantified range | Enabling mechanism | Long-term significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture toughness (MPa·m¹ᐟ²) | 7–10 | Transformation toughening | Structural reliability |

| Flexural strength (MPa) | 800–1200 | Fine-grained stability | Load-bearing use |

| Aging resistance (%) | >85 retention | Dopant and grain control | Service longevity |

| Property scatter reduction (%) | >40 | Process discipline | Manufacturing confidence |

| Functional adaptability | Structural to ionic | Defect engineering | Cross-sector relevance |

Conclusion

In essence, Zirconia Ceramic Evolution illustrates how scientific persistence transformed instability into advantage. Consequently, controlled phase behavior, disciplined processing, and defect engineering collectively elevated zirconia from geological curiosity to indispensable advanced ceramic.

Call to Action

ADCERAX provides engineering review and material selection support for zirconia ceramic components across structural, biomedical, and energy systems. Technical drawings and operating conditions enable targeted recommendations.

FAQ

Why is zirconia ceramic tougher than most oxide ceramics

Zirconia ceramic achieves high toughness through stress-induced phase transformation. Specifically, localized tetragonal-to-monoclinic conversion generates compressive stresses that slow crack growth. This mechanism elevates fracture toughness to 7–10 MPa·m¹ᐟ².

What caused early zirconia ceramic components to fail unexpectedly

Early failures originated from uncontrolled phase transformation during cooling. Moreover, coarse grain sizes and insufficient stabilization triggered volumetric expansion of 3–5%, producing internal cracking even without external load.

How does stabilizer content affect zirconia ceramic performance

Stabilizers such as yttria control phase stability and oxygen vacancy concentration. Lower contents preserve transformation toughening, while higher levels suppress transformation but reduce toughness. Therefore, composition selection balances stability and mechanical demand.

Why does zirconia ceramic require strict processing control

Zirconia ceramic properties depend on grain size, impurity level, and density uniformity. Deviations exceeding 0.6 µm grain size or 0.05 wt% impurities significantly increase aging risk and property scatter. Consequently, processing discipline defines reliability.

References:

-

Zircon is the primary natural host of zirconium, explaining why zirconia-related behavior was first observed through mineral inclusions rather than isolated oxides. ↩

-

Zirconia phase diagrams map composition–temperature relationships that guide stabilizer selection and concentration. ↩

-

Low-temperature degradation describes spontaneous phase transformation in humid environments over time. ↩

-

Statistical process control reduces property scatter by monitoring defect populations during manufacturing. ↩